Print History: The Bulaq Press Museum - Bibliotheca Alexandrina

The story of how the first printing press in Egypt became the core of a printing museum housed in a global institution

17 Nov 2021 | By Murali Ranganathan

Any mention of the city of Alexandria in Egypt conjures up visions of magnificence. Of the dozen Alexandrias founded by the conqueror-king Alexander, it was the only one on the continent of Africa and continues to flourish on its original site. Its fame rested on two iconic institutions built around 250 BC, a lighthouse and a library. Popularly known as the Pharos of Alexandria, the lighthouse, towering over one hundred metres tall, was considered one of the seven wonders of the ancient world. The Great Library of Alexandria was one of the largest libraries of the ancient world and was acknowledged as the fount of Greek knowledge for many centuries. The lighthouse survived for about 1500 years before a series of earthquakes destroyed it. The Great Library had a more unsure existence for six hundred years – destroyed and rebuilt a few times – before it disintegrated in the third century of the modern era.

Extremely proud of its five-thousand year heritage, Egypt initiated a long-term project in the 1970s to build a library and research institution in Alexandria which would commemorate the Great Library. The project became reality in 2002 when the Bibliotheca Alexandrina was inaugurated. One of the grandest library projects ever conceived with space for eight million books, the new avatar of the Great Library, like its predecessor, aspires to be much more than just a library. It hopes to foster the production and sharing of knowledge in a digital age while celebrating its multifarious heritage: Africa, Egypt, Islam, Hellenism, and Arabic culture. Its cavernous edifice houses numerous centres which support research in these areas and permanent exhibitions which highlight every aspect of the production and consumption of manuscripts and books. It is therefore no surprise that it also hosts a full-fledged printing museum.

Foundation Plaque of Bulaq Press

The Beginnings of Print in Egypt

Egypt, then a province of the Turkish Ottoman Empire, was convulsed by numerous tumultuous and landmark events in the initial decades of the nineteenth century: the conquest of Egypt by the French army under Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798, its expulsion by the joint forces of the Ottoman and British Empires in 1801, the weakening of Ottoman control over Egypt, the appointment in 1805 of Muhammad Ali Pasha (1771–1849) as the governor of Egypt, his efforts to overhaul the Egyptian economy, and the emergence of an incipient Egyptian nationalism. The invading French army had brought printing presses with them to Egypt and had printed circulars and proclamations in Arabic and French. But these were ephemeral military presses which departed with the retreating army. The Pasha initiated many new projects to modernize Egypt and one of them was the establishment of a printing press in Cairo.

The printing press was located in Cairo at Bulaq on the shores of the Nile. It began operations in 1822. The Pasha had sent Egyptian students to Italy to learn printing technology in 1815 and perhaps one of them was designated as the manager. Though officially named Dar El Teba’a (House of Printing), it was generally referred to as the Bulaq Press or the Al-Amiriya Press. Edward William Lane, a visitor to Egypt in the 1820s, provides an early description of the printing press and its setting in his book, Description of Egypt:

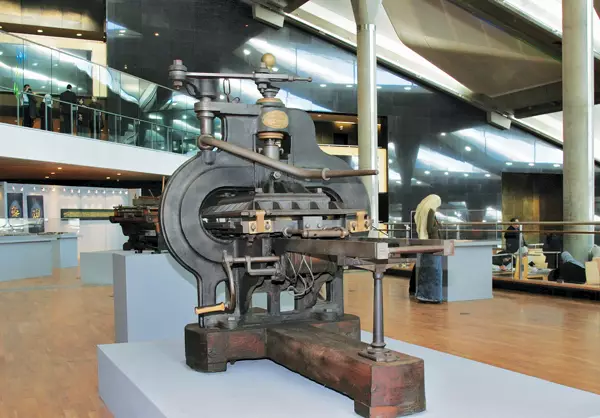

An early Stanhope printing press

Boo’la’ck [Bulaq], the principal port of the metropolis, has now a more respectable appearance, towards the river, than it is described to have had when Egypt was occupied by the French. The principal objects seen in approaching it by the Nile, from the north, are the warehouses and manufactories belonging to the government; which are extensive, white-washed buildings, situated near the river. In the same part of the town are seen large mounds of corn and beans, piled up in spacious enclosures, in the open air: such being the general mode of storing the grain throughout Egypt; for there is little fear of its being injured by rain. The great mosque, surrounded by sycamores and other trees, has a very picturesque appearance.

Boo’la’ck is about a mile in length; and half a mile is the measure of its greatest breadth. It contains about 20,000 inhabitants; or nearly so. … The principal manufactories are those of cotton and linen cloths, and of striped silks of the same kind as the Syrian and Indian. Many Franks find employment in them. A printing-office has also been established at Boo’la’ck, by the present viceroy [Muhammad Ali]. Many works on military and naval tactics, and others on Arabic grammar, poetry, letter-writing, geometry, astronomy, surgery, &c. have issued from this press. The printing-office contains several lithographic presses, which are used for printing proclamations, tables illustrative of military and naval tactics, &c.

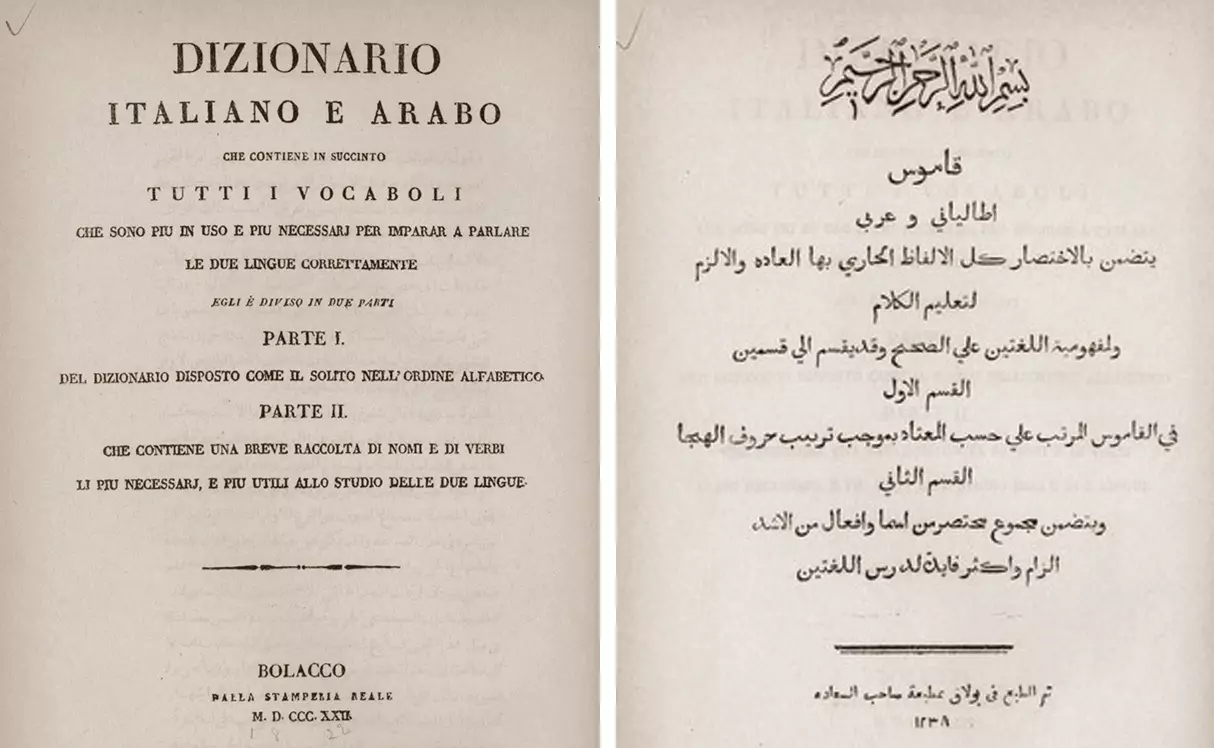

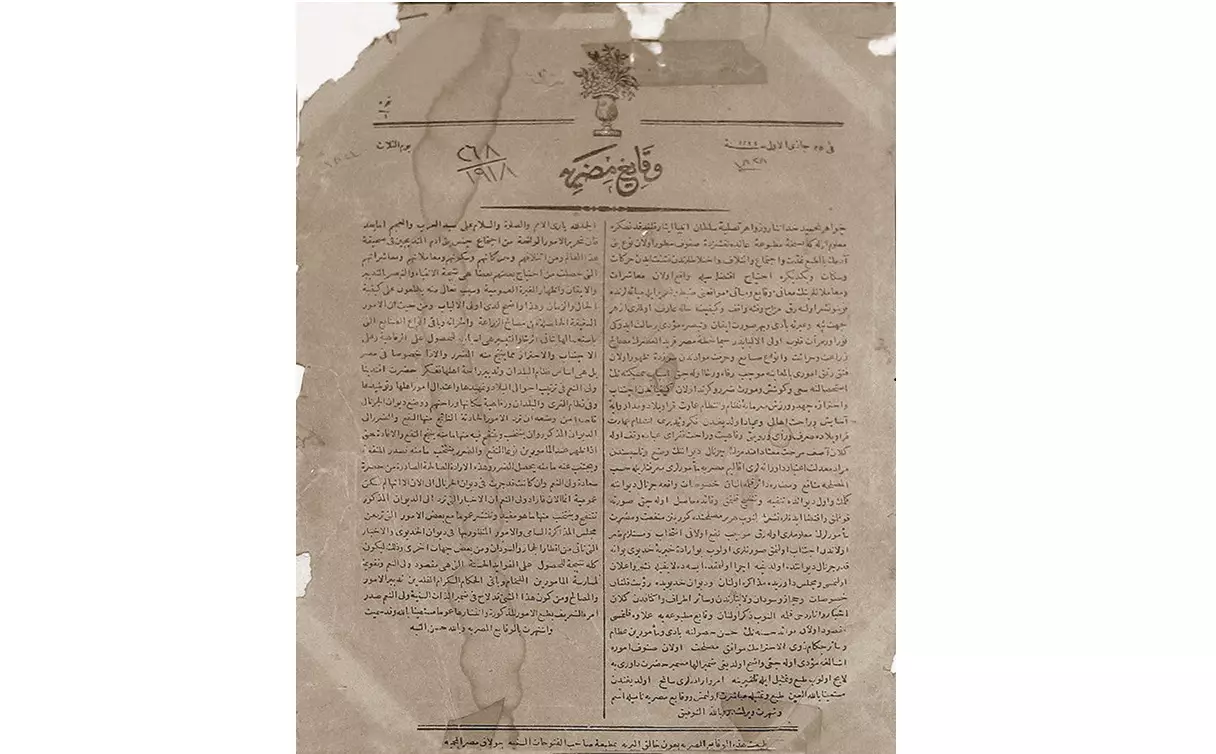

The first imprint – an Italian-Arabic dictionary – to be issued from the Bulaq Press in 1822 reflected the outward perspective which influenced its establishment. As lithography was still in its early years, this book is printed using type. But soon, the library invested in lithographic presses which were more amenable to printing in Arabic. The press was largely used for government purposes and for printing textbooks for the numerous educational institutions founded by the Pasha. Translation projects were initiated to enrich literature in Egyptian Arabic. The languages in which the printing was principally done were Arabic and Turkish. The very first printed Egyptian newspaper, El-Waqa’e Al-Misriya, was issued in 1828 from this press.

First imprint from the Bulaq Press, 1822

Through most of the nineteenth century, though the ownership of the Bulaq Press passed back and forth between the state and private individuals, the press was continually modernized and remained the premier printing press in Egypt. However, the first half of the twentieth century was a period of stagnation, not just for the Bulaq Press but for the entire country. It was only in 1956 when the modern state of Egypt emerged that the press regained its former glory. It was completely modernized and shifted to a bigger custom-built premises. The press continues to operate under the auspices of government and is currently celebrating its bicentennial anniversary.

Bulaq Press Museum

The typical fate of antiquated machines in a printing press has been the scrapyard. Most presses neither have the vision for preserving their heritage nor the resources necessary to protect it. However, many of the old machines and archives of the Bulaq Press, going back to the time of Muhammad Ali Pasha, were sent into storage rather than being scrapped. When the Bibliotheca Alexandrina and its numerous components were being conceptualised, one of the exhibitions which was proposed centred around the print heritage of Egypt. The Bulaq Press and its pioneering role in the development of printing in Egypt was well recognized. When an extensive search was mounted to discover traces of Egyptian print heritage, the remnants of the Bulaq Press were discovered to be in the custody of the General Authority for Government Printing Affairs. With the concurrence of the Egyptian Ministry of Foreign Trade and Industry, the archival material was transferred to the Bibliotheca Alexandrina. It formed the core of the Bulaq Press Museum which was inaugurated in 2005.

The material was in a degraded condition and, not surprisingly, none of the machines were in working order. It was difficult to repair hot-metal composing machines like Intertype and Linotype because of the non-availability of spare parts and lack of knowledge of restoration. However, a systematic restoration plan was put in place by which each machine was disassembled, each part cleaned, broken and missing parts replaced, and eventually the machine was assembled and refurbished. Much of the work was done in collaboration with printing museums in Europe and America. Wooden and metal Arabic type specially designed for the Bulaq Press is another highlight of the collection.

El-Waqa’e Al-Misriya, first printed Egyptian newspaper, 1828

The Bulaq Press forms the core of the printing museum and additional material from other sources are being collected to provide a representative history of Egyptian printing over two centuries. It intends to introduce visitors to the entire gamut of printing technology from hand composing to print-on-demand on the latest digital printing machines.

A role model for Indian libraries

India has many monumental libraries and knowledge institutions. Each major city has its own heritage library, many of them with a history going back to two hundred years and more. Some of them are institutions of national significance like the National Library in Kolkata, the Asiatic Society of Mumbai, the Madras Literary Society and the National Archives in New Delhi. They typically possess heritage buildings with iconic status. New libraries have been built at great expense such as the Anna Centenary Library, Chennai and Lilavati Lalbhai Library within CEPT University, Ahmedabad or being refurbished like the Hardayal Municipal Library in Delhi. Many new universities with a broad vision of knowledge and learning are being built on sprawling campuses and are investing large sums of money in developing knowledge infrastructure.

These institutions need to expand their vision and incorporate a printing museum into their plan. Collaboration with the printing industry and print historians could allow for the design of printing museums which not only cater to the needs of the institution and its constituents but also to the public at large. Will these institutions step forward?

Key Web Resources

www.bibalex.org/bulaqpress/

www.academia.edu/5583263/The_

See All

See All