Print History: Newspaper Historians of Bombay

Charting the growth of newspapers in Bombay in the nineteenth century was not an easy task but three scholars accepted the challenge

31 Jul 2023 | By Murali Ranganathan

Walking around old Bombay, one comes across streets with names such as Mumbai Samachar Marg, Janmabhoomi Marg, and Free Press Journal Marg, all named after venerable Bombay newspapers. Or landmarks named after people associated with newspapers: Horniman Circle, Adi Marzban Road, and Syed Abdullah Brelvi Road. This profusion of journalistic allusions underlines the prime role of Bombay in the development of Indian newspapers from the 1790s. Besides English, the three major languages in the city of Bombay were Marathi, Gujarati and Urdu. However, this newspaper history had barely been documented even 150 years later in the 1940s.

It is only in the 1940s and ‘50s that we find three pioneers venturing into this largely unchartered territory. None of the troika saw themselves as historians, much less print or newspaper historians. They were students of their respective languages and wished to delve deeper into its history and its growth. Newspapers and magazines, an important part of this evolution, had never been systematically studied in most Indian languages and constituted an arena where they could make a seminal contribution. The three of them registered as doctoral candidates with the University of Bombay and circumscribed their work in different ways.

Framing the Research

Though the University of Bombay had been established in 1857, the highest degree it awarded for the first eight decades was the MA degree. Candidates who wished to pursue advanced research in their area of study had to travel abroad to acquire a doctorate. It was only from the 1940s that the University began awarding doctoral degrees in its various faculties including the languages. The study of languages had developed numerous facets even in those early days: linguistics, literature, history and culture. Besides concerning themselves with Bombay newspapers, the three researchers had to define their studies in other ways.

Phagun Bhuraney (1919–1975) limited his study of English newspapers published from Bombay to the year 1900. He also considered only those newspapers which were conducted by Europeans (who were then known as Anglo-Indians), leaving out the few English newspapers edited by Indians. His reasons for limiting his study to 1900 was the fact that these Anglo-Indian English newspapers, whose coverage had been largely balanced for most of the nineteenth century, adopted, from around 1900, a strong pro-colonial stance and vehemently criticised the nascent Indian independence movement. Most of the surviving English newspapers he studied were preserved in the archives of the Bombay Government, the oldest issue being a volume from 1797. Some newspapers were also available at the Asiatic Society of Bombay. Though Bhuraney could not access the vast holdings of early Bombay newspapers at the India Office Library in London, he was able to procure a copy of the earliest available issue of the Bombay Courier from 5 January 1793.

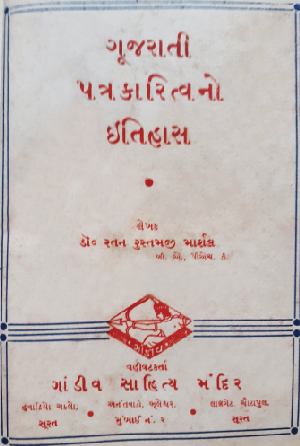

The research ambit of Ratan Marshall (1911–2011) spanned Gujarati newspapers from their start in 1822 until the 1940s, the period in which he wrote his dissertation titled ‘Gujarati Patrakaritvano Itihas’ [History of Gujarati Journalism]. Most of these newspapers were published from Bombay while the rest were published from Gujarat. Marshall was luckier than the other two because the two oldest Gujarati newspapers – Bombay Samachar (founded 1822) and Jame Jamshed (1832) – were still the leading Gujarati newspapers of the city. They had a functional and accessible archive going back to the earliest years and had also preserved volumes of other contemporary newspapers. Annual bound volumes of practically every Bombay Gujarati newspaper were also available at two city libraries: Mulla Feroze Madrassa and K. R. Cama Oriental Institute.

Ratan Rustomjee Marshall (1911–2011)

Maimoona Dalvi (1936–2009) framed her research project more broadly as compared to the other two. She sought to chart the growth and spread of the Urdu language in the city of Bombay and therefore engaged with Urdu in all its manifestations: prose, poetry, newspapers, printing presses, educational and cultural institutions, theatre, and much more. Her study is largely focussed on the nineteenth century, though her terminus is 1914, a year chosen for convenience rather than for any particular significance in connection with Urdu. The first Urdu newspaper was published in Bombay in 1824 but the earliest issues which Dalvi could trace were from as late as 1874. The few issues of Urdu newspapers which had survived were available at Karimi Library and Madrassa Mohammadiya, Jama Masjid Bambai. The Urdu resources were indeed meagre when compared to Gujarati or English but Dalvi made judicious use of them.

Gujarati Patrakaritvano Itihas (Surat: Gandeev Sahitya Mandir, 1950)

Biographical Notes

Phagun Hariomal Bhuraney was born on 22nd April 1919 in Sukkur, Sindh, which was then a part of the Bombay Presidency. On completing his schooling, he shifted to Bombay at a young age for his further education. After acquiring a MA in English, he taught undergraduate classes in various Bombay colleges. Bhuraney might have considered returning to Sindh in the mid-1940s but the upheavals related to Partition and Independence meant that it was his family which migrated to Bombay and its suburbs. In the early 1950s, he registered for a doctorate with the University of Bombay. His dissertation was accepted in 1956.

The affluent sections of the Sindhi community, whose educational institutions had been left behind in their native land, tried to recreate them in India. As a fellow Sindhi, Bhuraney would certainly have contributed to these efforts. He therefore worked as a principal in colleges across north India in cities like Bikaner (Rajasthan), Moradabad (Uttar Pradesh) and Palwal (Haryana) besides Bombay and Delhi. He finally became the founder principal of Adarsh Degree College in Ajmer, Rajasthan, which position he held when he died in 1975.

Maimoona Dalvi (1936–2009)

Ratan Rustomjee Marshall was born in Bharuch, Gujarat on 14th October 1911 in a Parsi family. His father was connected with the textile industry. After completing his BA degree in 1934, Marshall joined the Surat Parsee Punchayet and served in various capacities for nearly seven decades. While working on his doctoral dissertation for nearly ten years in the 1940s, he was the Joint Secretary of the Punchayet but by the 1950s, he had become its Secretary. Ratan Marshall also took a leading part in Surat municipal affairs and was a Second Class Honorary Magistrate for the city.

Marshall was also a committed writer on Parsi community affairs and a steady stream of books emerged from his pen. All of Marshall’s writings are in Gujarati, the primary language of the Parsis until the 1980s. His earliest books – biographies of Surat Parsis such as Ardeshir Bahadur, the famous policeman, and Bhimji Hadvaid, the miraculous bonesetter – were published in the forties. He was also a regular participant in the conferences organised by the Gujarati Sahitya Parishad and was the convenor of the Gujarat Parsi Parishad, a body of Parsi writers and intellectuals. Marshall lived for nearly a hundred years and, until his last days, pursued his interest in Gujarati literature.

Maimoona Dalvi hailed from a Kokni Musalman family which was native to Bombay. Born in 1936, she completed her schooling at Anjuman Islam Girls High School. She went on to graduate in Urdu from the University of Bombay and registered for her doctorate soon after. When she submitted her thesis in 1960, she would have been among the youngest persons to do so. She taught Urdu at the Ismail Yusuf College for many decades. Though she continued to be interested in the history of Konkan and its folk culture, she published sporadically until her death in 2009. A few minor essays appeared from her pen during her long teaching career and a substantial book on Urdu folk songs was published after her retirement.

Structuring the findings

In his doctoral thesis titled ‘Anglo-Indian Journalism in Bombay (upto 1900)’, Phagun Bhuraney charts the growth of English newspapers from their start in 1790 by giving a decade-by-decade account of their development. Bhuraney is particularly interested in the contents of the newspapers and the lives of those associated with them as he notes in his Introduction:

It is in these papers, and mainly in these writings, that we get a portrait of the Anglo-Indian Society which in its amplitude, richness and intimacy outvies all other portraits. It is in these sheets that we see, through Anglo-Indian eyes, new and interesting facets of the Indian society and of the scenes and sites of Bombay. Not only do these newspapers add considerably to our knowledge of the social history of the times but they form a valuable supplement to the political history of the rulers and the ruled.

After a broad review the English newspapers through the nineteenth century, he examines every aspect of the newspaper trade in great detail: news, advertisements, trade and commerce, literature, relationship with the Bombay Government, editors and readers, and typography. Though he did not overlook the deep prejudice harboured by a few of these newspapers, especially in the latter decades against Indian national aspirations, his concluding assessment of their role is positive.

Ratan Marshall was the only one among these three who investigated the advent and development of print technology in Bombay. His first two chapters are concerned with the growth of printing in the Gujarati language and how the first Gujarati types were cast in Bombay as far back as the 1790s. He traces the evolution of Gujarati types from its first use in the Courier Press to the improvements made by the Nirnayasagar Press and the Gujarati Type Foundry.

He then proceeds to tackle the newspapers themselves; of the over hundred Gujarati titles that he identifies for the period from 1822 to 1942, he provides a detailed description of the career of twenty-five leading newspapers. He charted the growth of Gujarati journalism in three phases: Gujarati newspapers before 1880, the year in which the landmark newspaper Gujarati began publication in Bombay, newspapers from 1880 to 1919, and from 1919 onwards, when M K Gandhi took over the reins of the Ahmedabad newspaper, Navjivan. He was of the opinion that the Gandhian era of Gujarati newspapers had ended by the early forties. He was able to analyse the broad trends in Gujarati journalism, its reaction to a constantly changing colonial legal framework, the emergence of a nationalist spirit. He also could chart the emergence of differentiating features like humour, satire and the use of illustrations.

Dalvi’s doctoral dissertation, later published as a book titled Bambai mein Urdu [Urdu in Bombay], was the most comprehensive engagement with Bombay in the nineteenth century through the medium of Urdu. Drawing on a wide variety of printed and manuscript sources, which had hitherto never been used by scholars, Dalvi documented the socio-cultural growth of Bombay by chronicling the growth of institutions, cultures, and social groups in the Bombay Urdu milieu. Starting with a brief account of the history of Bombay, she goes on to survey the prominent Urdu-speaking families of Bombay. She further plotted the rise of an Urdu literary culture by studying the works and compositions (both print and manuscript) of Urdu writers who were based in Bombay. She then examined the growth of religious, educational and social institutions, libraries, and printing presses, and finally concluded her dissertation by chronicling the growth of Urdu as the primary language of entertainment in Bombay.

Bambai mein Urdu (Mumbai: 2017, reprint)

The review of Bombay newspapers formed one of the six sections of Dalvi’s dissertation. She chronologically discusses each individual newspaper that she could identify. She identified nearly a hundred Urdu newspapers and magazines published from the city until 1914. Some of the entries are perfunctory, but for those newspapers which she could actually peruse, she analysed their content and tried to construct their history. Dalvi frequently provides extracts from the newspapers to illustrate the language, diction and style of their editors. Having adopted the tazkira (a chronologically arranged biographical dictionary) as a model for her writing, Dalvi did not provide a narrative analysis of her findings. Nor could she look at the close interactions between Urdu, Persian and Gujarati newspapers in that period.

Epilogue

In many ways, the contributions of Marshall, Bhuraney and Dalvi were pioneering. Marshall’s dissertation was the first to be accepted by the University of Bombay in a non-English language. He believed that writing a history of Gujarati newspapers in their own language would be more meaningful. Likewise, Dalvi’s submission was perhaps one of the first doctoral thesis to be submitted in the Urdu language.

None of the three scholars seem to have researched the newspaper and print arena after completing their dissertations. Bhuraney’s peripatetic life perhaps precluded any further work on Bombay newspapers. He does not seem to have made any efforts to publish his dissertation during his lifetime and it has been shrouded in obscurity ever since. On the other hand, Marshall’s research was published soon after he completed his dissertation. After his dissertation was accepted by the University of Bombay in 1949, he was felicitated both by his fellow Parsi brethren as well as by the citizens of Surat. The felicitation prize of Rs. 2100 was used, at Marshall’s suggestion, for publishing the dissertation in 1950. It was soon recognised as a classic and the Bombay Government, in 1956, presented him with a thousand rupees as an award for the best Gujarati book. The book continues to be a standard reference text for all those who are interested in Gujarati journalism and printing. He later published an essay on the Parsi contribution to journalism. Dalvi’s dissertation was published in 1970, nearly a decade after she was awarded her doctorate. It has become a standard reference book for all aspects of Urdu in Bombay. Before her death in 2009, she was hoping to revise and update her book; a reprint edition of the book appeared in 2017.

As early as the 1950s, these newspaper historians were lamenting the non-availability of original material and worried about the precarious condition of the surviving volumes of the newspapers. Dalvi frequently mentions Urdu newspapers which had been accessed a few years earlier by researchers but were not traceable when she sought to peruse them. Bhuaraney notes that, “The records themselves are on the verge of collapse; they may be lost to us for ever. The sooner, therefore, the study is undertaken, the better for our knowledge of the history of the times.” Seventy years later, Bhuraney’s prophetic words have come true. The volumes of English newspapers have collapsed under the weight of repeated mishandling. The Gujarati newspapers, which were available from as early as 1822, have simply vanished into thin air. The Urdu newspapers have fared slightly better merely because the repositories which held them were inaccessible to researchers for many decades.

The institutional apathy of archival custodians and successive depredations of generations of fly-by-night scholars have made it impossible for researchers to replicate or build on the work of these newspaper historians. Nevertheless, the time has come for these areas to be revisited by a multitude of researchers. Biographies of individual newspapers and the people associated with them have yet to be written; the interplay between newspapers of different languages are yet to be considered; the contents of their volumes have barely been analysed; and, the printing presses where the newspapers were printed have not been studied.

Notwithstanding the depleted availability of the source material, one hopes that a new generation of newspaper historians will write themselves into existence.

See All

See All