Print History: Ganges Printing Inks - Colours for the Nation

At a time when Indian printers had to import most of their printing inks, Ganges Printing Inks manufactured them locally and soon dominated the market. Its range of colour inks revolutionised the packaging industry

30 Apr 2024 | By Murali Ranganathan

In 1938, as the Scandinavian winter was setting in, a young man from Norway set off on a voyage across two continents and two oceans to Calcutta. After qualifying as a chemist, he had been working in a remote corner of Iceland in a factory which processed herring into fishmeal and oil. And, just a year later, he was travelling halfway across the world to make a fresh start, and hopefully, a career. At the end of a journey which lasted over a month, he disembarked in Calcutta at the dead of night.

The young man, whose name was Emil Fjermeros (1914–2012), had secured an appointment as a chemist in Ganges Printing Inks at their factory in Howrah. According to the Norwegian memoir which Emil Fjermeros wrote six decades after he first arrived in India, his intention was to stay in India for three years, the duration of his contract with Ganges Printing Inks. But the world had other plans for him.

India Ink

The tradition of using inks for writing in India can be traced back to two millennia and more. Ink was used to write on a variety of surfaces: palm leaves (tada patra), birch bark scrolls (bhurja patra), cloth, leather, pottery, stone, and eventually, paper. Ink was an important component of scribal culture and recipes for making ink are available in many Sanskrit texts. Manufactured from lampblack or soot collected by burning a variety of organic material, the production of ink was essentially a cottage industry. P K Gode, in his review of ink in ancient India (1946), gives a recipe for ink used to write on paper.

[Ink] is made by mixing a coffee-coloured infusion of roasted rice with lampblack, and then adding to it a little sugar, and sometimes the juice of a plant called kesurle. The labour of making this ink is great, for it requires several days continued trituration in a mortar before the lampblack can be thoroughly mixed with the rice infusion, and want of sufficient trituration causes the lampblack to settle down in a paste, leaving the infusion on top unfit for writing with. Occasionally acacia gum is added to give a gloss to the ink.

Black ink was predominantly used and was famous enough for it to have its own geographical indicator – India Ink – even though the term now generally refers to ink from China or Japan. Inks in other colours, especially red and yellow, were also used in Indian manuscripts. Not unlike textiles, every village or town would have produced ink for local consumption. However, these inks were not commercially viable products. Many attempts were made to manufacture these inks on a larger scale. For example, Narayan Hemchandra of Bombay, who fancied himself an engineer, tried to manufacture and market writing inks in the 1860s but, like many others, could not maintain quality standards.

Ganges Printing Inks Factory, Howrah, circa 1950

The properties of inks used for printing were completely different from the inks used for writing. With the development of more complicated printing machines, the technical specifications of printing inks became more rigorous. In these inks, which were viscous compared to writing inks, the pigments were typically dispersed in oil-based carriers. By the start of the twentieth century, almost all the printing inks consumed in India were imported from the United Kingdom and elsewhere in Europe. The major suppliers were Coates and Winstone, pioneers of modern printing inks. A European-owned firm, Hooghly Inks, had been manufacturing printing inks in India since 1913.

By the late 1920s, swadeshi was again becoming prominent in the national discourse. Besides textiles, products which had been traditionally manufactured in India, like ink and paper, became the focus of the swadeshi movement.

MK Gandhi obsessed over ink and constantly exhorted his young correspondents to use it: “Write in ink and shape the letters well.” “Write with ink and make each letter as beautiful as a carefully drawn picture.” Small-scale ink manufacturers from places such as Guntur and Chandernagore began sending him supplies of swadeshi ink in the hope of receiving his certificate of approval. Though he continued to use these inks, Gandhi recognised that ink manufacture required “expert chemical knowledge.” Though he could admit that “Village [ink] and village paper is not a combination I can yet advertise,” he persisted with them.

Besides ink for writing, printing inks also became a focus of the swadeshi movement. In Bombay, Dolatram Kashiram & Co, who were the Indian selling agents of LB Holliday & Co, one of the largest manufacturers of dyestuffs, began manufacturing printing inks in 1930. Though imported dyes were used to manufacture these inks, the conversion process rendered them swadeshi. They were marketed under the unambiguous brand name, Swadeshi Printing Inks. By June 1931, Bombay Chronicle, a newspaper with nationalist sympathies was endorsing its printing inks, “which compare favourably with foreign inks both in respect of quality and price. The Bombay Chronicle press has been using these inks for the last fortnight and has hitherto found no cause to regret the choice.” Gandhi also recommended Swadeshi Printing Inks to those printing presses who were looking to go swadeshi. Dolatram Kashiram & Co continued their marketing efforts all through the ’30s but do not seem to have found much success.

A Norwegian enclave in Calcutta

The technology for the manufacture of pigments and dyes was revolutionised towards the turn of the century and this, in turn, opened up innumerable possibilities in the world of printing inks. Inks in a wide range of colours could be manufactured at reasonable prices. German companies such as BASF, Bayer and Hoechst (which would later merge to form IG Farbenindustrie) were at the forefront of this change. However, it was uneconomical to import these dyestuffs into India to make printing inks because the import duty on the finished product was one-fifth that on raw materials.

It was under these circumstances that Gulbrand Løchen (1893–1953), a Norwegian businessman, registered a company with the name Ganges Printing Ink Factory Limited in 1927. The initial capital investment was rupees one lakh. Løchen, through his firm, G Løchen & Co, was one of the biggest paper importers in India and was well acquainted with the printing trade. In 1927, the Government of India, with a view to safeguard the interests of the Indian paper industry, introduced a protective duty on certain categories of paper. This move seriously affected the trade in imported paper and could have been one of the reasons for Løchen to diversify into printing inks.

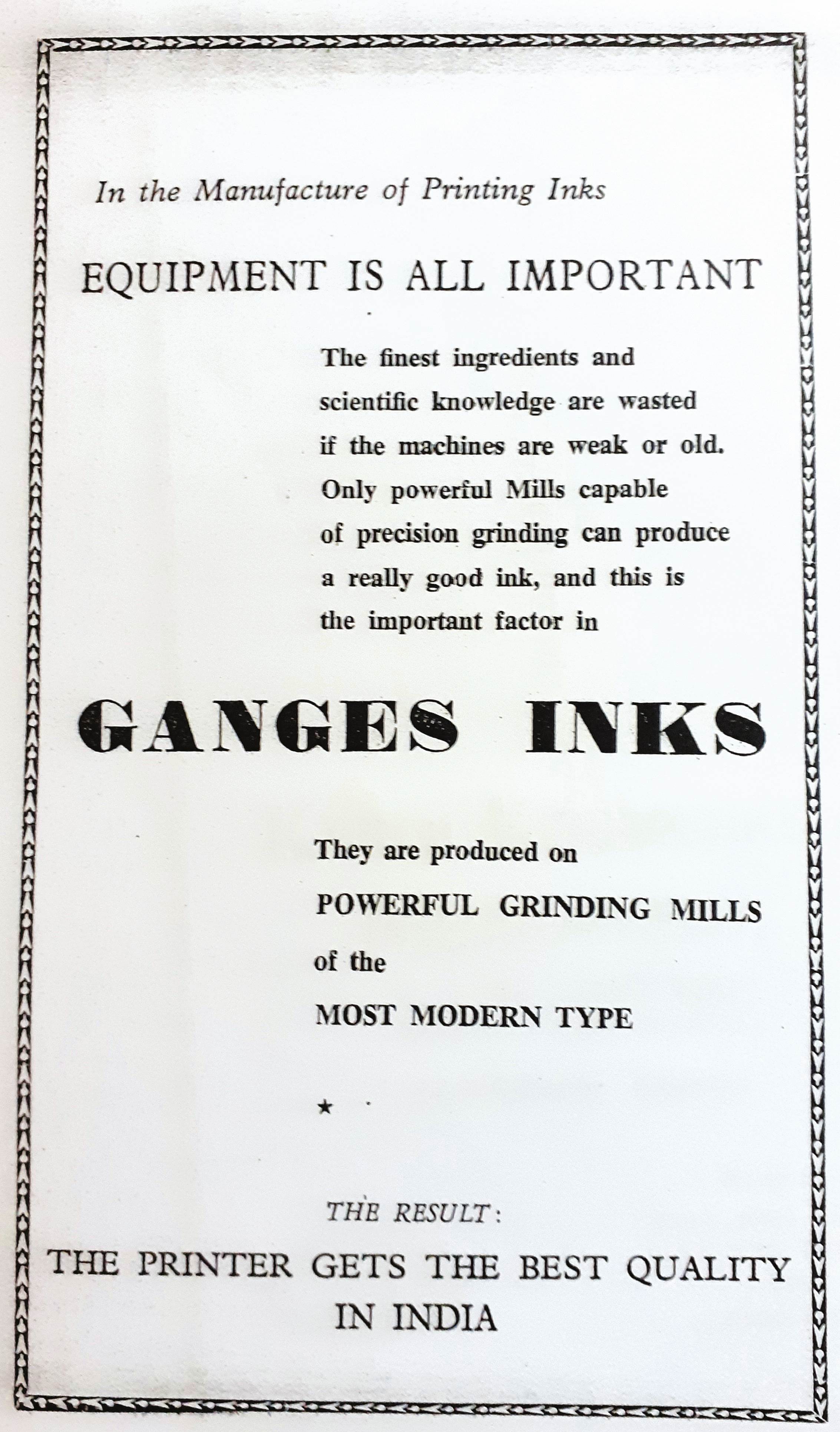

Løchen set up a manufacturing facility in Howrah in the vicinity of the Botanical Gardens. Though most of the employees were Indian, Løchen had a core staff of Norwegians who handled important roles. Sverre Gylseth assisted him in the commercial side of the operations. Viggo Hansen was the chief chemist, a critical position because he was the custodian of the recipes which were used to manufacture inks. Ganges Printing Inks found it difficult to break into the Indian market because large printing houses were suspicious of locally manufactured printing inks which had a reputation for variable quality. However, Løchen persevered, and by 1938, Ganges Printing Inks had a foothold in the inks market.

When Hansen was leaving the firm in 1938, Løchen turned to Norway to find a replacement. From a pool of fifty Norwegian applicants, the best candidate was the twenty-four-year old Emil Fjermeros. He had completed a four-year diploma in organic chemistry at the Norwegian Technical Institute in Trondheim. After a rather cold welcome in Calcutta, Fjermeros soon settled down in his new job. He learnt the ropes of ink manufacturing from a departing Hansen. In June 1939, Løchen had to leave India at short notice because of medical issues. The responsibility of managing Ganges Printing Inks devolved upon Gylseth and Fjermeros. While Gylseth took over the commercial and marketing aspects of the business, Fjermeros oversaw the technical side and the factory operations. The days were very busy, as Fjermeros recalls in his memoir:

We ran three shifts in the factory. Since I was the only one with access to the safe with the secret ink-mixing recipes for all our customers, I had to load all the print batches, do all the calculations and oversee quality control. Other larger printing ink companies had general inks, but we specialized in more ink mixes and niche colours for demanding customers. I started learning Hindustani right away, although most workers spoke Bengali. Some staff, including a few chemists and managers, spoke English. We shipped our goods from the factory by ox-driven carriages to the Howrah railway station. The Indian railways were very good.

New opportunities, new challenges

A few months after Løchen’s departure to Norway, the start of the Second World War signified new opportunities and challenges for Indian industry in general, and printing inks in particular. No longer could printing inks be imported freely thus providing local producers with a chance to capture the market. On the other hand, neither could the pigments and dyes needed to manufacture printing inks. Willy-nilly, printing inks had to go swadeshi.

A number of Indian-owned companies entered the fray. In Bombay, Dhulekar Brothers, who had been the agents for a German ink manufacturing company, began to produce and market inks under the brand name, Gripoli Printing Inks. A little later, the Sathayes of United Ink & Varnish Co also diversified into printing inks at their factory in suburban Bombay. In Madras, Vishakan Printing Ink Works had been established in the mid-1930s. Though it had invested in state-of-the-art equipment, including three Torrance grinding mills from England, its business was floundering due to lack of working capital. In 1939, it was acquired by a family of traditional bankers as their first foray into industry and renamed Nanco Printing Inks. It was managed by KS Narayanan who later became the chairman of the Sanmar group of companies. The new owners soon turned it around but realised that Nanco could not meet the specifications of larger customers. In his memoir, Friendships and Flashbacks (2002), Narayanan recalls the hurdles:

Almost immediately after we took it over, the ink factory began its climb out of the red. What we needed now was a marketing boost, a buyer who would place large orders. The large orders at this time were placed mainly by the daily newspapers; in Madras, that meant The Hindu and the Indian Express. They would not take us seriously, I think, because there was a technical problem with our ink, which cropped up only when it was applied to the fast-spinning rollers of the big presses that ground out the dailies.

As the rollers whipped around, a cloud of black particles flew up from them, making a sort of sooty miasma in the room and coating the technicians until they were black in the face.

Most Indian ink manufacturers would have faced these technical roadblocks. Ganges Printing Inks, with its longer experience and superior chemistry, could easily cater to large customers like the government and newspaper presses. Though they could no longer import dyestuffs from IG Farbenindustrie in Germany, they developed other sources through their Norwegian contacts. The Second World War proved to be a turning point for the company and it emerged as the dominant player in the Indian printing inks market. The manufacturing facilities at Howrah were no longer sufficient to cater to the rising demand. In early 1945, it undertook a major revamp. A new factory was constructed on an enlarged site. A large office block which could accommodate laboratories, quality control and even a printing press was also built adjacent to the factory.

In 1943, a famine devastated Bengal and Calcutta was witness to scenes of extreme human deprivation. Fjermeros did not stand aloof in those circumstances: "1943 was a difficult year in Calcutta with the war leading to rationing, inflation and mass starvation with 2 million people dying. I was able to arrange with the British authorities that the factory workers (and their families) would be able to secure rice and lentils at fixed prices. This act was not forgotten by the workers who presented me with a plaque signifying their gratitude after the war."

The end of the war also meant that Emil Fjermeros could finally go back home. Instead of the planned three years, it was seven years before he could meet his family in Norway. He also met Løchen, the major shareholder of Ganges Printing Inks, who was very pleased with how the company had grown in his absence. After a stint in New York, during which he studied the latest developments in offset inks and varnishes, Fjermeros returned to India in 1949. He was now the managing director of Ganges Printing Inks.

Expansion and eclipse

The fifties were a period of rapid growth for Ganges Printing Inks and Fjermeros spearheaded this expansion. A factory was set up in Bombay in 1950. Nanco Printing Inks of Madras was acquired from the Sanmar group in 1953. This was followed by a factory in Delhi. From being completely dependent on imports for raw materials, Ganges Printing Inks developed local sources for many of them. Linseed oil, one of the primary ingredients, was now available in India. An oil extraction factory was set up on the premises to extract oil from tung nuts sourced from Assam. Except for the finest pigments and extenders, all other dyestuffs were sourced locally.

Instead of merely relying on its technical prowess, it also adopted a strong marketing strategy. Ganges Printing Inks was, perhaps, one of the first companies in India to commission a corporate video in 1952. Not only did it take its customers through the entire production process, it underlined the emphasis at Ganges for quality control and timely delivery. With an annual turnover exceeding rupees one crore by the early sixties, Ganges Printing Inks had a one-third share of the Indian printing inks market. It also exported inks to Pakistan and Burma, and in one special order, sent a batch of security inks in 1943 to Formosa (later Taiwan or Chinese Taipei) so that the Chinese government-in-exile could print currency notes.

With the rapid growth of the Indian retail sector, packaging began to take on a more important role than ever before. Cartons and labels were being printed in multiple colours. Ganges Printing Inks with its portfolio of sixty-four readily available colours was easily able to cater to these needs. As Fjermeros recalls in an interview with a Norwegian newspapers in the 1962,

An Indian today is no longer satisfied with buying cigarettes in "loose weight". He wants them in packages. And he wants to buy his tea in colourful tins and his soap in pretty packaging. And printing inks are needed for that. As education gains more and more traction in Indian societies, and as literacy and the desire to read increase, the need for colour printing rises again. The countless street booksellers in the Indian cities, with their brightly coloured arrays of paperbacks in Hindi, Bengali, Urdu, and of course English, testify to that. In India, there is a pure mania for colourful calendars and it is often the only form of painting that can be found in small Indian homes.

After 1947, the shares of Ganges Printing Inks were acquired by Indians who soon held a majority share. Most of the Norwegian staff returned home gradually with much better opportunities now becoming available in Europe. With the exit of Emil Fjermeros in 1967, Ganges Printing Inks was no longer the Norwegian enclave it had been for a few decades. His departure also presaged a rather precipitate fall for Ganges Printing Inks as its new owners could not keep pace with the rapid technological innovations in the world of printing.

I am very grateful to the family of Emil Fjermeros, especially his nephew, Espen Fjermeros and his grandson, Emil Evnum, for their generosity in making available material – news cuttings, photographs, corporate films – related to Ganges Printing Inks from the family archive, and for sharing translated excerpts from the Norwegian memoir of Emil Fjermeros.

.PNG)

.PNG)

.PNG)

See All

See All