Pranav Parikh: Still Hungry For Print - The Noel D'Cunha Sunday Column

In conversation with Anand Limaye of MMS, the

Lifetime Achievement Awardee, Pranav Parikh talks

about his early days in Harvard and how TechNova

became an innovation hub for all things print.

A Sunday Column special (with inputs from Mumbai

Mudrak Sangh)

23 Feb 2020 | By Noel D'Cunha

Anand Limaye (AL): This morning at the TechNova headquarters, we would like to know about your journey from your Harvard University days to being the fourth largest plate manufacturer and the sixth-largest chemical manufacturer in the world. Tell us more about your beginnings?

Pranav Parikh (PP): Well, it's been a journey full of challenges and learnings. I think that's the only way I can describe it.

AL: What were the challenges?

The biggest challenge was to master the nuances of the printing industry because this industry is one of the most challenging of all industries. At least, that's the way I see it. Not only is one required to master technology, one also needs to have an aesthetic sense. Moreover, it requires a manufacturing mindset. And like any other business, one must have good interpersonal skills to manage customers, as well as employees. Believe me, these skills don’t come easily!

AL: You are a Harvard graduate ...

Yes, Harvard Business School was my training ground. Before Harvard, I graduated from Sydenham College, Mumbai. And the only challenge then was how to bunk classes and get attendance marked by proxy. However, in the business school environment, we were made to work 80 hours a week, presenting a minimum of three cases a day. It meant performing an in-depth business analysis of each case and then presenting it to a class of 200 students. There were enough brilliant guys shooting down whatever presentation one made in terms of the right thing to do for the business.

The key takeaway was the tenacity to keep working at a problem until one got to the bottom of it. There is never the right answer for anything. There's always a better way, so the training created the ability to keep drilling. The second learning was to argue and debate with respect – not with arrogance, mind you – in defending our point of view. I can say, however, that I'm still learning the technology part; especially how to deal with its challenges and frustrations.

AL: Even today, I grapple with technology in the printing and packaging industry. That’s why I am curious to know why did you choose this industry?

I had the two choices when I returned home after Harvard: the family business of clearing and forwarding, warehousing. I worked there for a considerable period of time. It was a service-oriented business and not highly technology-oriented. The other option was joining the printing business, which was a letterpress print-shop at that time.

AL: You started the press?

My brother Jagdish and his partner started the printing press with the Albert & Hamm machines. I tried Koenig and Bauer letterpresses; they needed someone to be fully hands-on. I found the printing world to be much more exciting, because of the challenge to master a range of skills, and technological processes in a much wider spectrum of sources of frustration, brought about a greater sense of satisfaction. This made managing a printing plant a richer business experience for me. Moreover, all this experience of printing gravitated towards the aesthetic sense was also an essential part of the experience, making it a great combination. Technology keeps changing, as do customer and worker demands. I found it to be a challenge that attracted me to this business.

AL: Did your brothers inspire you? What did you learn from them?

Oh yes! A lot of learnings from my eldest brother, Arvind, who is a Padma Bhushan awardee. He looked after the clearing and forwarding business. What one learned from him was to spot business opportunities, for which he seemed to have an uncanny intuition and which I tried to emulate. He can easily empathise with people in need; he exudes warmth almost naturally. So those are three things that I tried to emulate from him.

AL: What about Jagdishbhai?

Just like me, Jagdish is a Harvard Business School product. I tried to learn from him the professional management skills. The other thing was perseverance; if he took up something, he really went after it. Those are the two things that helped me through my professional life.

AL: Would you please elaborate on your creative training methodology that led to the creation of so many print masters in our industry?

The creation of print masters was in their hands. I had all the mistakes they made in the print business to learn from.

AL: Please share your method ...

In terms of my methodology, there was a lot of emphasis on training. The focus was not just on what to do, how to do it, when to do it, where to do it, but most importantly, why you are doing what you're doing. The emphasis on theory was very high. The zero-defect print was our aim as we were conscious of very high costs, and customer orientation was always emphasised. Accepting one's mistakes without being defensive was a very important feature of the training.

AL: What is IQ-EQ-SQ?

I think one of the things was the whole concept of IQ-EQ-SQ (intelligence, emotional and spiritual quotient) which was actually made a part of the overall business culture.

I think intelligence quotient measures the competence part. But equally important, if not more, is the emotional quotient: the maturity, the interpersonal relationships, the ability to accept one’s shortcomings without being defensive, and dealing with people with respect. The most important was the spiritual quotient. It was, and I hope it still is, an essential part of the culture of our organisation.

I acquired a deep sense of spirituality from my father; an unshakeable faith in the guy up there and I believe that everything is done by Him and His Will, and whatever happens, happens for the best. We try to inculcate that kind of spirituality without any preaching, but simply practising what we believe. And, I hope there are elements of it in TechNova. Besides, there are a whole lot of other aspects, such as self-awareness and humility among others. It is difficult to detail them all in a short answer.

AL: Four decades ago, after leading the print industry with Printwell, you entered the plate manufacturing business at a difficult time.

Printwell was probably the leader and not I personally.

AL: Why did you select this business? Please explain how TechNova was born on the shop-floor as a research and development initiative, transitioning from Printwell to TechNova.

We started TechNova in 1971. Then, there were barely 10 plate manufacturers in the world. Printwell, like all other printers, was facing extreme problems with offset plates. At that time we were using thick zinc, ball grained plates. I won't go into the entire process but there was graining and there was coating, exposing deep-etch processing, after which it went to the press. Invariably the process failed for some reason or the other, and then one started the entire process again. In other words, the biggest bottleneck to quality was the offset plate. And we experienced it day-in-day-out in Printwell. And registration problems also occurred as the plates used to stretch. Further, there were single colour machines, not machines with colour options.

Through the problems we faced, we spotted the need, not just for Printwell, but for the entire industry. We were all sailing in the same boat. And, since there were only ten plate manufacturers worldwide, we thought there would be good scope if we succeeded in making plates. We took the help of a British scientist, ex-Kodak Alan Vincent, who worked with our research team in setting up TechNova as a laboratory. That’s how the journey began.

AL: What was your USP in those days?

"We became quite successful in replacing zinc with aluminum ball grained plates to start with, and then, of course, the whole generation of plate technology development came to be.

AL: In what way?

In the past 49 years, since 1971, ten plate manufacturers grew to 200 and now it's back to ten. So, the whole industry is gone through incredible growth and then shrinkage or consolidation. There are about ten plate manufacturers outside of China, and maybe another significant eight to ten in China. That's the nature and structure of the industry today.

AL: What were the lessons you learnt during those days?

Well, it's classic playing out of the competition. There is innovation; there is product development. This is so during the initial stages when the pioneers get the biggest market share and have the best bottomlines. Later the technology becomes freely available and can be replicated, leading to a mushrooming of companies when the pricing comes down.

China played a big role in bringing the prices down; thanks to their government subsidies. And, all those that had higher costs than the lowest cost producer started shrinking and disappearing. So, the plate industry has completed a full cycle. Now, one has to see who will be the last person standing.

AL: Pranavbhai, in a way Alan Vincent epitomises your philosophy of IQ-EQ-SQ. Your meeting seemed to be one of those wonderful flukes that transpire on this planet. Would you tell us how you met, and his contribution?

He is the father of technology, so to speak because we got started thanks to his involvement. And, he's a born Christian, so he is deeply spiritual in his own way. I don't know whether to call him religious or spiritual, but whatever. He was teaching at the printing school, JIPG where I too conduct lectures. So we crossed paths many a time and that’s how we connected.

In those days we were working with multi-mask and all those manuals. We hired Alan Vincent as a consultant because he had that background. One day it hit us that we were doing all this work up to the stage of positives with the mask and colour corrections that had improved many times, which resulted in us having achieved a certain level of excellence in positives. Yet, we were losing it all at the platemaking stage. Block making was also a challenge. The Nerkers and Poonawallas were leading or monopolising the photoengraving industry, so it was very difficult to get copper sheets for making blocks. Again, thanks to Alan’s ideas, we bought aluminium sheets which were available, copper-plated them and then did powder-less etching. Though we actually succeeded in that venture, it was not economical.

Parikh receiving the Scroll of Honour from the Hon’ble Governor, State of Maharashtra, HE Shri Bhagat Singh Koshyari

AL: Was Alan Vincent only a technologist?

Alan Vincent was a lateral thinker. Apart from product development, he had a great impact on the company culture. When I suggested that we work together, his one and the only condition was “that the company will be run in a strictly ethical manner. No incentives to be given to customers to buy anything. No avoidance of taxes.” That's exactly what we wanted to do. Though I had doubts about whether we would succeed in the ethos of the Indian business, he told me to “leave it to the guy up there. If you have faith that doing the right thing is the right thing to do, then we will succeed.” He certainly had a deep impact on the ethical culture of the organisation.

AL: Please elaborate on the research you have done on the plates.

I would love to!

The evolution of the plate technology began with the aim of making plates that were robust to run on the presses without failures and good enough to reproduce the smallest, finest dot, even when using stochastic screening. Run-length, resolution, and quick start-up with the minimum wastage were also important aspects in realising this goal.

Zinc plates were far from achieving this, so we developed grained plates on aluminium. I'm not referring to the bio-metallic part of it, which was for photo engraving block making. This is pure aluminium treated in different ways, so that it had a surface for water receptivity and non-image areas and hydrophobic to receive the ink. The micro-grained aluminium plates went through a lot of research. This was the first stage.

AL: This was stage one. What was stage two?

The stage two was the consistent research for eliminating variability and reducing the number of steps, thus reducing the cost. With these three objectives, we went from micro-grained aluminium plates to stage one wipe-on plates. So instead of coating and deep etching, which was time-consuming, we had a wipe-on coating which was wiped down with a sponge, exposed and then developed using a lacquer.

AL: This plate became an instant hit with newspapers.

Yes. The credit should go to senior Kasturi of The Hindu Group for pushing us to develop a plate for newspapers. They were using the rotary letterpress process and the deep etch plates took ninety minutes before they could go to the press. Newspapers could not wait that long and needed to move to offset to avoid waste of time. But they could not move to offset because the plate was a big limitation. We were asked to develop a plate that could be processed in ten minutes.

AL: Ten minutes?

We developed the wipe-on plate with 10-11 minutes process time. However, there was the inconsistency of wiping with the wipe-on, so we went to pre-sensitised plates which required chemicals for processing. Further, the run lengths were a question. So there were limitations in wipe-on plates. The shelf life of the coatings was the next criterion that pushed us into pre-sensitised. So, pre-coated, pre-sensitised plates were developed for positive, as well as negative working. All one had to do was expose and develop and the plate was ready to go to the press.

Soon, we found that there was variability because the pre-coated, pre-sensitised plates required films and paste-ups and all kinds of different variable processes. That was when we moved to the CTPs (computer to plate); again both positive and negative working. CTP has two kinds of lasers: thermal and violet. Violet is adopted mainly by the newspapers and has its own advantages and thermal is used mainly by commercial printers and packaging printers.

The next was the chem-free plates, which did not require any chemicals or water. These are environmentally-friendly with the same performance characteristics. And finally now, to eliminate other variables, there is a processless plates, which is exposed and goes straight on the press.

AL: What was your mantra during this plate journey?

The whole journey was to speed up the process of printing, making it fail-proof and cheaper. The manufacturing process had to be totally defect-free and non-variable and these technologies enabled us to do these things. In between, thanks to you, were the polyester plates.

AL: Please share the polyester plate journey.

For small offset printers, they were using paper plates, imaged using a typewriter or a Xerox camera. So from paper plates, they used the same imaging process on thin aluminum foil plates. So, we came up with polyester plates, double-sided, which could be imaged on a laser printer. Thus, high resolution and instant imaging can be used on both sides and printed from both sides. These were called NovaDom; and the United States was the largest market for these plates. What made us very proud was that it won the GATF InterTech Award; till date, the TechNova is the only Indian company to have won it. The product is produced till date and it is an international success.

AL: Can you elaborate on that?

Well, it was a breakthrough, to say the least.

NovaDom catered to the bottom of the pyramid; the fragmented and unorganized market that others had given up on. Therefore, investment in technology, creating NovaDom, empowering this ignored market segment, and witnessing their migration upwards in the pyramid is a momentous journey. What I am proud of is the thought process that enabled this journey; an investment that is worth our while and empowering the small guys to grow.

AL: NovaDom must be the proudest moment for ‘Make in India.’

To elaborate on ‘Make in India;’ it was certainly the first of its kind in the world. We had stiff competition from a British company, from an American company. But, by God's grace, because of the quality of TechNova product and the lower cost, we were able to compete.

AL: Why so?

Whatever has a noble purpose, profits follow even though that's not the primary motive or objective. It allows us to do more, something that serves a bigger purpose. And this for us is successful, because it becomes a cycle of doing things that are bigger than us.

Our basic theme for developing products is that hopefully it is successful and is welcomed by the industry. And then what? Then we keep improving it so as to get a dominant market share. Having got the dominant market share, then what? Unless we come up with the next generation of products, one can stagnate. This effort makes the current product obsolete.

AL: Obsolete?

Yes. So we've had so many obsolescent-built processes. So many of TechNova products have been killed by our next-generation products. And that gives impetus for consistent product development.

AL: You took a big risk in the 1980s and recently at the turn of the century. You travelled across India. Why did you embark on that journey using your own personal investment? You were a man on a CTP mission.

I guess it's the noble purpose philosophy that drove me.

The whole pre-press phase was so cumbersome, so clumsy, and so variable. If one aspect of standardisation is missed in any one processing step, the ultimate damage is done when the plate goes on the press and the plate fails. So, we felt that we had to ensure that despite all the prepress operations, which were operator-dependent, the positive had to be right.

AL: Quite true.

Why couldn’t we do something to image the plate without a film, so that all the variables that went into making a positive or a negative could be eliminated? Now, I don't remember clearly who, but we found that this concept had already started becoming acceptable in the West, especially in Europe. At that time, Agfahelped us to develop the coatings and the processing, so that we entered into a technical collaboration agreement with Agfa. They helped us with the CTPs; and we were amongst the few CTP manufacturers at the time. That seemed to be the right answer for the industry, so we undertook the Digital Yatra traversing the length and breadth of India.

AL: You're also capturing data, getting a sense of market trends. So when you embarked on this CTP digital journey at the turn of the century, how were you so certain it would work out?

You know, the there is something called romance. So you fall in love with an idea, then you justify it and rationalise it. And then there are always enough number of reasons to prove that your idea is the right one to pursue.

AL: Pranavbhai, you often talk about timing in business. What is the timing?

To get the timing right, however, requires backing off, creating a distance between your love for a concept and the reality of turning it into a business success. That detachment from being the creator or the owner, or the possessor of the idea and translating it into an investment proposition; I think, in this process the objectivity, the attitude, and the ability to collect and analyse the right data plays the key role.

After the process, one may kill the idea one once romanced with. What did Professor Shoji Shiba call it? Kill your baby. So many times you've given birth to a product and then you’ve got to kill it. It seems like a daunting prospect. It is, indeed, but we have done that. If it has failed to serve the purpose for which the product is invented, there is no point continuing with it. It is a disservice.

AL: I think it's been not just in products, but it's also in services and business processes.

True. The distribution of RTCS (real-time computer systems ) was done way ahead of time or the bundling of the solution of plates and CTP equipment. Thus, the whole logistics backbone now became a huge competitive strength.

AL: Any new innovation?

The latest innovation is our TechNova shopfront. We are trying to have everyone order online and then eventually turn the e-commerce platform a marketplace for the industry. The TechNova shopfront will be an entire ecosystem providing solutions by selling single products to multi-product packages, to solutions from the TechNova imaging ecosystem. The platform not just sells our products but a complete basket of products and solutions with alliances and marketing products.

AL: Do you think small and medium printers like me should use cloud-based analytics solutions to be future-ready?

Frankly, and to put it bluntly, you have no other choice.

Cloud-based, pay-as-you-use solutions are the right ones for small and medium businesses. Because one cannot afford anything other than cloud-based service solutions, that don’t require much infrastructure investment – computers, software development, maintenance, trained human resource, and more – to reap the data-analytics benefits. It is OPEX (operational expenditure) or subscription model rather than a CAPEX (capital expenditure) model. The latest technology becomes available to you based on the subscription you choose.

AL: The TechNova’s old warhorses have always impressed me with their capabilities and specialisations; and they are all endowed with this contrarian spirit. How were you able to identify them, not only by their individual talent, especially knowing that to build a team, there would need to be a common purpose, yet a cognizant recognition of each member’s contribution to the whole, as well as identify their potential as heads of projects?

I can give you a fancy answer, but I won’t. It's all up to Him – the guy up there.

AL: This entails more than a simple answer. Would you please elaborate?

The right people come to us at the right time. And, then, by and large, we invest in them. Our philosophy is to grow from within, instead of continuously hiring and firing. Don't have a critical parental attitude towards people; a nurturing parental attitude is much better. And, this helps each team member to overcome their complexes and sharpen their talents. That's how, I think, everybody reaches their potential.

AL: How does such a team succeed?

The effort at TechNova is to create an environment where the team feels comfortable making mistakes and learning from them, besides learning from each other without rivalry. Now, it's not easy to get top performance with what some people may call a very lenient attitude. But it works; we are proof of it.

AL: What are these conversations at TechNova about first ‘they would do things anyhow and then it became know-how’? Also, our contacts from your company talk about your magician’s bag of ideas? What are these two things?

It was Jeevan (Bhatt) whose values have impacted the organisation. It is his catchphrase: Don't do it somehow; Do it with know-how.

AL: How so?

I say, we can transplant values by serving as an example. Demonstrating that certain values can work if they are practised consistently. People may emulate them. One might try to emulate values by lecturing; lecturing doesn't work. To be able to appreciate value, one has to feel it at the gut level. All values come out of spirituality. Say one is spiritual (don't ask me to describe what is meant by spiritual), then the person is a source of ideas and values. It rubs off onto whoever comes into contact with the person.

One has to practice caring and nurturing people. And trying to set an example. When one fails, accept their weakness by recognising that even though they may have done something in a way that was not the right way. However, also recognise the fact that the failure as added to the lessons we learned. One can try and rationalise these things into a training programme. There are training programmes to inculcate different value systems. One must remember that the training programmes have their own value; but genuine belief in something beyond us makes all the difference in instilling values.

AL: What has been the contribution of somebody like Professor Dr Shoji Shiba, the Japanese quality expert?

He's made a great contribution in giving us: a value system, and a bag full of tools, such as problem-solving tools, planning tools, training tools, change management tools.

He instilled a way of thinking-out-of-the-box and using the tools for what they are worth and not get entrapped into just using the tools. He taught each one of us to use a tool as an aid to lateral thinking. For example we do post-its and every element of a problem is posted on the wall. And, he would then encourage the team members to find out the missing links to problem-solving and the solutions would emerge layer after layer.

If one is not able to think through a problem to the nth degree, then one has not got the right answer. And, Prof. Shiba always says: there is no one right answer to a problem. There is always a better way; keep searching for it till you find it.

AL: Professor Shiba says breakthrough' management, rather than core competencies and TQM, is the key. What did he share with you?

He says CXOs should have three eyes. One eye to oversee everything in the organisation and in the manufacturing process. This eye keeps a close watch on performance within the set parameters. Once the process stabilises, the second eye takes over to drive continuous improvement; this is the Kaizen eye. Then the third eye is the Buddha eye, which is focused on the breakthroughs.

According to Prof. Shiba, 75 per cent of a CEO’s time should be focused on looking into the future and not analysing daily reports. A CEO should be able to see the invisible and the unknown in the future. And then there is the fishbowl principal: a CEO should jump into the fishbowl or the challenge at hand, get to the bottom of it, get the hands dirty, then jump out and see it from a larger perspective, and then search for a solution.

AL: You have taken many risks to break the clutter. Other than CTP, what was the one risk that succeeded?

Well, I think technology!

Every new product we introduce, which will make the current product obsolete is a risk. Our name, TechNova is a combination of technology and innovation; thus innovation and thereby risk-taking appetite is in our DNA. I think every innovation has a lot of trial and error before something succeeds. What one sees out there is a successful story, but behind it is a lot of continuous improvement and learning to make it better to really arrive at the right product, or process, or service that addresses that customer pain point and needs. Plenty of iterations.

AL: In business, everything is a big risk.

Every new product has been a risk. The biggest risk for TechNova was the T-5 factory. Our fully automated state-of-the-art manufacturing line was a huge risk.

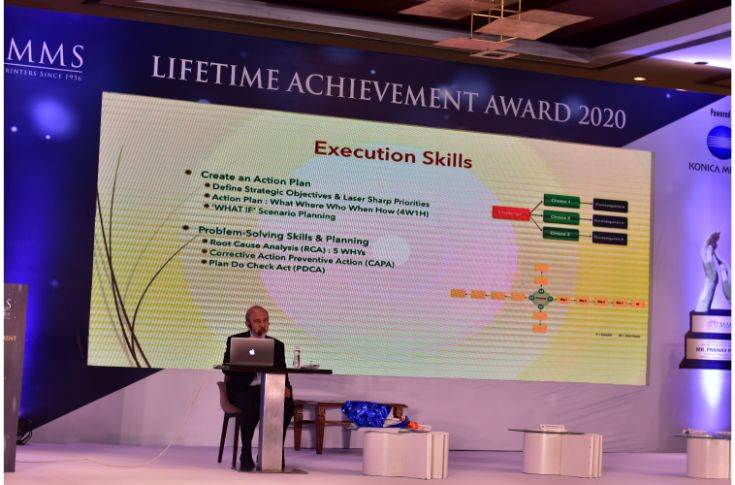

Parikh: making a presentation on - Attributes of success - during the event

AL: Why so?

I think at every stage in the business lifecycle of the company to take a leap forward in terms of investing in manufacturing technology capacities, was a risk for the company to take on a bigger project than you have ever done. In that sense that was the biggest risk at that time in 2008. And also compounding the problem was the overall external environment. The combination of our biggest investment in a very deteriorating business situation and a financial situation was one of the biggest risks.

AL: Can you expand a little bit about the innovation team if that can be shared; who are the brains that drive it and how does it work?

Everyone you meet in TechNova is supposed to be a part of our innovation team. Whilst we have a dedicated research and development (R&D) team, there is no definite role-restriction on anyone beyond the R&D team. There are not only a certain set of people to focus on breakthroughs, or others to focus on control aspects, or on Kaizen. It's not like that. It is everybody's job. And, some of the best ideas come from completely unsuspecting people.

AL: But who listens and captures these ideas?

Well, product development groups are made. They are supposed to generate ideas by having brainstorming workshops, idea generation and improvement workshops, and Kaizen workshops. They are supposed to generate ideas, document them, refine them, and implement them.

AL: What about market feedback?

Obviously the voice of the customer is very important. The one thing TechNova has always been consistent about is making the customer the epicentre of everything. Listening to the customer, constantly improving the product to serve the customer, even if it means making products for a few customers, so that we cater to their needs. So I think that besides innovation, this has been the organisation’s signature service, making it customer-centric, which has been its integral ethos.

AL: Pranavbhai, what would be your advice for the friendly neighbourhood printer?

I think, the context is where does one stand a highly competitive space, which is the aegis now. Perhaps one can say that there is always room at the top and room at the bottom of the pyramid.

Room at the top, however, requires excellence. Not only in terms of quality of products and service, but also in customer relationships. Basically excellence in everything. Then one definitely has enough scope in the printing industry. So there is room at the top for those who excel. Then there is room at the bottom for those who excel in cost transformation. So low cost becomes the theme if one is to survive at the bottom of the pyramid.

The real problem is the in-between situation. If one has to escape this middle-of-the-road, run-of-the-mill tag one has to migrate to being excellent and claim the top spot or challenge the market by becoming the low cost service provider. This is the way I look at it.

AL: Many in the industry know you as a spiritual business leader. You are moving towards adhyatma. Would you discuss this attraction and practice?

You will first have to explain to me what adhyatma means!

I would love to be in a situation where there is a spontaneous flow of thoughts and actions, with a complete sense of surrender, while being a witness to what one is doing. That's what I would like to be doing, but the ego comes in the way, in a big way. Detachment is easier said than done; one can pretend to be detached, but it doesn't happen easily. Emotions come in the way.

So yes, I would like to progress in the direction which is witness attitude and complete surrender, and believe that whatever happens is for the best. But, I'm far from it, therefore, I have that desire to move towards that direction, but the ability to do so is a big question mark.

Parikh with daughter Sheena, who is the joint managing director at TechNova

Pranav Parikh Mantra

Having a noble purpose is the first inspiration, and the other is to make our product obsolete before somebody else does it.

If you want to be in business, let the purpose be noble. Having faith in the right thing is the right thing to do.

See All

See All