Printing partnerships for India’s publishing future — The Noel D'Cunha Sunday Column

Dr Amit Sharma, director for publishing operations at HarperCollins Publishers India, and Ashok Pahwa, business manager, HP Indigo and PWI commercial, Indian Subcontinent market, HP Industrial Print, discuss the realities of publishing, the role of technology, and what printers must do to become trusted partners. Read on…

06 Sep 2025 | By Noel D'Cunha

HarperCollins is one of the world’s oldest publishing houses, with a history stretching back to 1817. Its Indian subsidiary has been present for more than three decades, building a dual presence in trade publishing and education. “We are one of the few publishers who are both in the trade segment and school education,” says Dr Amit Sharma, director for publishing operations at HarperCollins Publishers India. The company publishes around 350 new titles each year and manages a backlist catalogue of over 3,000. This combination of frontlist and backlist gives it breadth, but also complexity.

The Indian journey has not been linear. Sharma recalls that 2008 was a turning point, when the surge of eBooks forced publishers to strengthen metadata systems. “Our product catalogues had to become robust and available in digital formats,” he explains. A second milestone came in 2013, when HarperCollins entered the school education segment. That decision significantly increased scale, but also exposed the company to the highly competitive and price-sensitive textbook market.

Pahwa views these milestones from a technology supplier’s perspective. “It is striking that HarperCollins chose to operate in both the biggest segments of Indian publishing,” he says. “Trade builds brand and education builds scale. But both need printers and suppliers to deliver different outcomes.” For him, HarperCollins’ history demonstrates how publishers must continually adapt to technology shifts and market pressures.

Untapped growth and complex drivers

India’s scale is obvious: the world’s most populous country, 80% literacy, the second-largest English-speaking population, and a youthful demographic. These factors create demand across segments. “Children’s books, test preparation, spiritual publishing and English imports are all growing,” Sharma observes.

Yet he argues that the underleveraged area is technology. Analytics, predictive tools and faster decision-making remain weak across most publishers. “We need data intelligence for quicker and better decisions,” Sharma insists. Pahwa agrees, adding that the opportunity lies in aligning digital printing with this intelligence.

There is also untapped potential in making more international content available in India. Sharma notes that the country, as the largest English-speaking market after the US, could absorb far more global titles if print runs were smaller. “They may not sell in big quantities per title, but they can sell in wider variety,” he says. Pahwa stresses that this is precisely where digital presses matter. “Digital allows publishers to sell breadth, not just depth,” he argues.

Speed as the new metric

Publishing in India has always been cost-driven, but Sharma believes speed is now equally decisive. “The world is moving towards faster publishing,” he explains. Social media, BookTok and celebrity book clubs can suddenly trigger demand for a title. Without quick replenishment, publishers lose sales.

Pahwa concurs. “Speed is what technology can solve. Digital lets you print what you want, where you want, and when you want,” he says. This agility is not just about machines but about processes. Leaner supply chains, decentralised fulfilment and modular workflows are becoming the norm.

Both agree that speed cannot come at the cost of quality. Binding errors or production delays damage reputations, especially in education. For HarperCollins, the expectation is that printers should deliver books back within days of sending files. Sharma is clear. “Lean processes and speed are what we look at when choosing a printer.”

Security and the piracy challenge

Piracy continues to drain revenues, particularly in academic and test preparation markets. Sharma is frank about its impact. “Unauthorised PDFs and pirated editions are widely circulated. It erodes revenues and discourages investment in new content,” he says.

Pahwa highlights the parallel with the film industry, which has combined legal enforcement with technological solutions. “Publishing must learn from other industries. Without strong IP security, international publishers hesitate to release high-value titles in India,” he warns.

Security is not only about content theft but also about how printers handle files. HarperCollins expects its partners to demonstrate robust safeguards when managing foreign content. “If Indian printers are handling content of foreign publishers, security has to be very, very careful,” Sharma emphasises. For both voices, IP protection is as much a competitive differentiator as price or capacity.

Counting the real costs

For decades, publishers in India focused on unit cost per copy. That logic is no longer sufficient. “Total cost of ownership is the real thing and right thing to look at,” says Sharma. He divides costs into three categories – manufacturing, distribution and infrastructure.

Distribution can be as damaging as production. Shipping, discounts and returns all weigh heavily on margins. Infrastructure costs, from warehousing to digital platforms, add further pressure. Inventory is the most dangerous trap. “We make a title, we send it to market, and we do not know how the market will behave. Obsolescence is a constant risk,” Sharma says.

Pahwa underscores that technology adoption must respond to this reality. “Digital is not just about unit cost, it is about reducing obsolescence and returns. The savings come from eliminating waste.” Both voices converge on the idea that predictive P&L, informed by data and technology, is now essential.

What printers must deliver

The criteria for printers are clear. “Consistency in service, communication, scheduling and reliability,” Sharma lists. “Speed is next, because lean processes are what we look for.”

Pahwa adds that publishers want printers to be partners, not vendors. “It is not only about the cheapest rate per copy. It is about who can integrate into your workflow, support distribution, and ensure content security.”

Cost remains relevant, but only when tied to innovation. Sharma explains: “A 5% discount is not what matters. What matters is how innovative you are in sourcing materials, adopting technology and improving processes.” The message to printers is blunt: compete on value, not only on price.

Both voices see the future as partnership-driven. “Publishers do not just want printers, they want strategic partners,” says Pahwa. The right partner manages content securely, delivers quickly, and aligns with the publisher’s supply chain.

Sharma reinforces the point. “What we want is a printer who can handle our content, handle operations in the right way, and deliver faster to market.” The expectation is not transactional but systemic. Printers who meet these standards become indispensable.

Tech to tame publishing chaos

At the PrintWeek-HP-Reddington India webinar hosted on 19 August, industry leaders unpack how digital printing is reshaping publishing, from academic journals to vibrant children’s books, offering agility and precision in a market hungry for speed and diversity.

To a question from a Guwahati publisher sparks a lively discussion. It’s a query that captures the pulse of India’s evolving publishing landscape: how can digital printing tame the chaos of academic publishing’s frequent revisions and unpredictable demand? The answer, delivered by experts from HP and India’s printing industry, reveals a broader story: one of a sector embracing technology to meet a growing appetite for education, diversity, and speed.

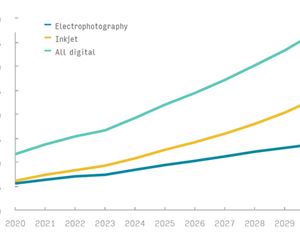

India’s publishing market is surging. Demand for K12 education books is climbing, and the call for titles in 22 Indian languages grows louder, as one panellist notes during the webinar’s closing remarks. Yet, serving this diverse readership demands mastering complex processes with precision. Digital printing, the panellists argue, is the key to navigating this terrain, offering flexibility and efficiency that traditional offset methods struggle to match.

Anthony Paguirigan, an HP specialist, takes the onus to address the academic publishing conundrum posed by Dibyajyoti Sharma of Red River Publication. “It’s an interesting topic. It’s not new, and it’s really relevant today as we navigate through the increased POD, or very short run or book of one,” he says, referring to print-on-demand (POD) systems that allow publishers to print as few as one copy at a time. This capability is a game-changer for academic publishers, where revisions are frequent and demand can be erratic. “HP has developed a solution, basically in collaboration with our partners, to provide a relevant solution to these kinds of requirements in the market,” Paguirigan explains. He points to a network of satisfied customers and workflow partners who tailor solutions to publishers’ needs, whether based on volume, timing, or specific priorities.

Dr Amit Sharma, a panellist with a background in newspaper publishing, builds on this, drawing parallels to the high-pressure world of newsrooms. “Publishing is slowly becoming what newspapers used to do: faster to market. And it has to be correct. It has to be done at a particular time,” he observes. For Sharma, the magic lies in lean workflows that unburden publishers from tedious file management. He describes a streamlined process enabled by HP’s infrastructure: “On the front, it looks like we just send them an indent with a unique identifier, which is mostly an ISBN. We just say this ISBN, these many copies immediately, so keeping the files intact, like with the naming convention, and backing it up with the EDI.” This electronic data interchange (EDI) ensures version control, preventing costly errors in reprints. Sharma urges academic publishers to take cues from journals, which have already mastered these workflows. “Journals are already doing it; academics, I think, it is still happening, but they can learn from how journals are managing their print potential,” he says.

The conversation shifts as another question, this time from Vani Data of ITC Paperboards and Speciality Papers Division, probes HP’s collaboration with Indian paper mills. Paguirigan is quick to respond. “Collaboration with paper mills is not new to HP. That has been one of the pillars of our success, especially in India.” He describes established programmes where HP tests and co-develops substrates with local mills to enhance digital printing adoption. “We have worked with several Indian paper mills already. We have tested it, we have advised them,” he says, inviting ITC to explore these opportunities. This synergy between technology providers and local manufacturers underscores India’s push to tailor digital printing solutions to its unique market needs.

A question about digital inks, posed by Partha Sarathi Mukherjee, prompts Paguirigan to delve into the technical side. “There are two types of ink that we have here. We have the Indigo inks, and then we have the water-based inks,” he explains, hinting at the complex science behind their formulation. While he suggests a dedicated session to unpack the R&D intricacies, his response highlights the sophistication underpinning digital printing’s reliability.

Children’s books, a high-growth segment, bring another dimension to the discussion. A questioner notes their design-heavy nature, with vivid colours and high saturation, and asks if digital printing can compete with offset for such titles. Ashok Pahwa, another panellist, draws a parallel to coffee table books, where HP’s Indigo technology shines. “When we talk about coffee table books, our technology, which is an HP Indigo technology, is a worldwide leader,” he says, citing Indian customer Silverpoint, which uses large-format Indigo machines to produce stunning results. “Any high-quality children’s book which falls into that category, or close to that category, we definitely have a solution for very high coverage, high-quality children’s books,” Pahwa asserts, offering a proof-of-concept to sceptics.

The webinar’s closing remarks crystallise the stakes. India’s publishing industry, from academic texts to children’s literature, is at a crossroads. The demand for education and linguistic diversity is not just an opportunity but a challenge to “master a complex process, and as usual, do it smartly,” as one panellist puts it. Digital printing, with its agility and precision, is proving to be the tool of choice. Whether it’s managing short runs for academic reprints, ensuring vibrant colours for children’s books, or collaborating with local paper mills, the technology is enabling publishers to focus on content while leaving logistical headaches behind.

As Paguirigan, Sharma, and Pahwa make clear, the tools are ready: streamlined workflows, tailored substrates, and advanced inks. The question now is whether India’s publishers will seize this moment to print smarter, faster, and bolder, meeting the needs of a nation hungry for knowledge and stories.

See All

See All