Print History: A Whiff of Turpentine: U Ray and Sons, Calcutta

Indians have hardly contributed to the development of printing technology. A print pioneer from Calcutta in the 1890s proves to be an exception

31 Mar 2025 | By Murali Ranganathan

Printers had grappled with the challenges associated with printing illustrations for centuries but the question became particularly acute after the mechanisation of printing in the late nineteenth century. Traditional methods of printing illustrations, such as woodblocks, mezzotint, aquatint and chromolithography, were no longer adequate to the constraints of cost and speed imposed on printers.

Modern presses were printing books and newspapers in ever increasing print runs, some going into the hundreds of thousands. Printers were constantly in quest of solutions that would not only shorten the time required for pre-press activities, that is those processes which convert an image into a printable surface, but also ensure that the printed image met quality specifications. The quality could range from coarse work for newspapers or very fine work for art books. Print technologists on both sides of the Atlantic were experimenting with techniques that would enable illustrations to be printed simultaneously with textual matter.

From the 1850s, the advent of photography and the use of the camera in the pre-press stage gave rise to numerous photo-mechanical processes, referred in shorthand as “process” in trade circles, for printing illustrations. For instance, photogravure, perfected in the 1870s, was a technique by which very high-quality prints could be produced by intaglio printing, that is, using a plate where ink was held in grooves below the surface of the plate.

However, photogravure, like other intaglio methods, could not be used in conjunction with letterpress printing since the latter was a relief printing process in which the ink lay on the raised portions of the printing plate. A variety of photo-mechanical block-making techniques that would create a relief printing surface were experimented with in the nineteenth century. By the 1890s, half-tone photography had emerged as the process most favoured by printers but the results were not altogether satisfactory. It was still a hit-and-miss proposition, something that printers with deadlines and budgets could ill afford.

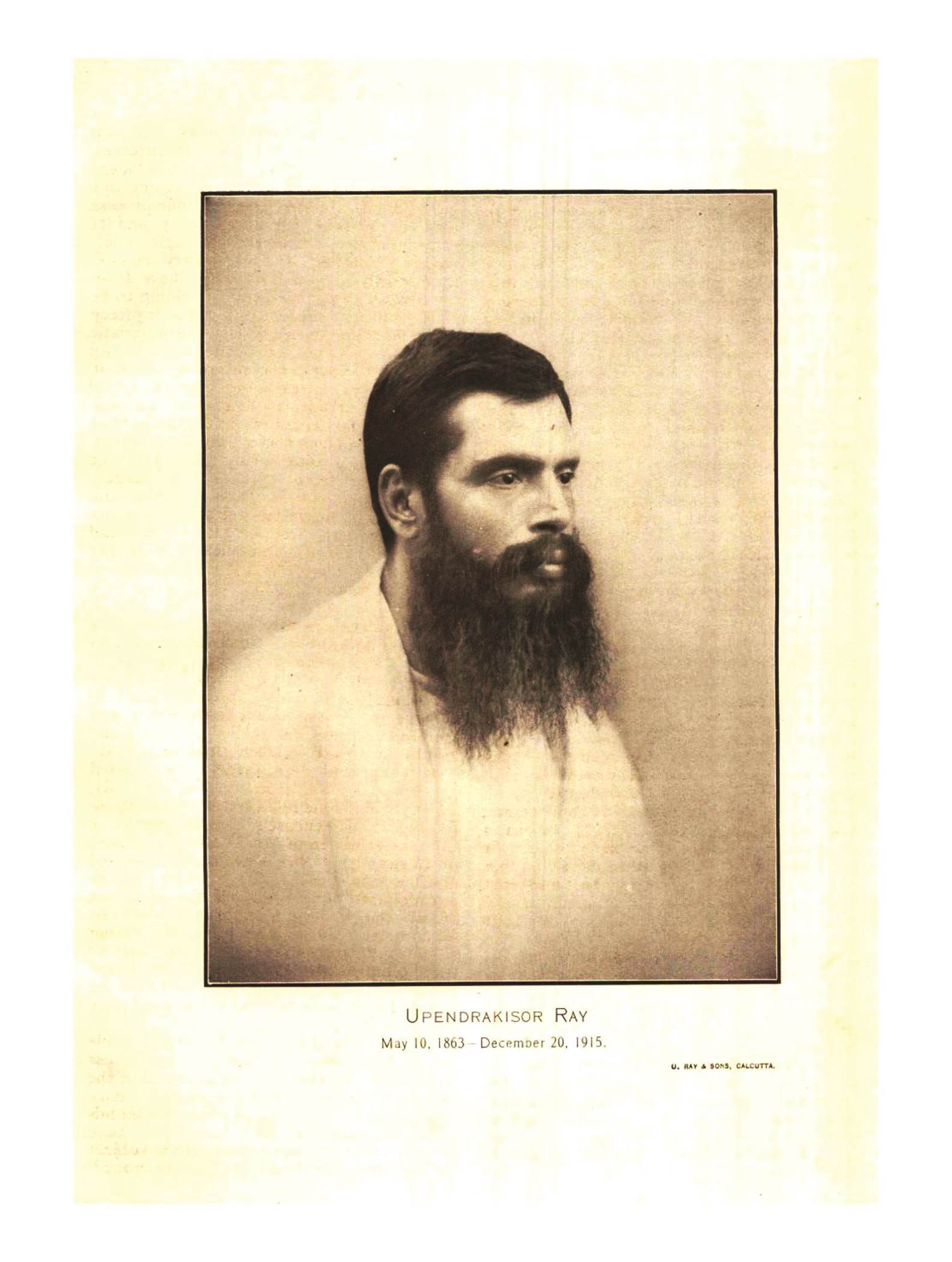

Indians were, inevitably, on the margins of the experimental mainstream. Not only were they physically at a distance from the main centres of research, their voices either lacked credibility or they did not have access to the forums where their work could be recognised. There was also the added risk of misappropriation of ideas and inventions by European intermediaries. Very few Indians had invested in the equipment, including the process camera used to manufacture the half-tone blocks, necessary to print illustrations using photo-mechanical techniques. The variability in results was perhaps the most daunting reason which dissuaded commercial printing presses from this venture. However, a young man from Calcutta, Upendrakishore Ray Chaudhuri, with no prior experience in printing was willing to take his chances.

Becoming a block maker

Upendrakishore Ray Chaudhuri (1863–1915), like his son, Sukumar Ray, and his grandson, Satyajit Ray, is a household name in Bengal. Born into one of the leading families of Bengal, he was one of the pioneers of children’s literature in India. His writings, which he illustrated himself, continue to be consumed avidly by generations of children and adults. He was also a composer whose tunes continue to be sung, an accomplished violinist, an amateur astronomer and a social reformer. Counting the likes of Rabindranath Tagore and Prafullachandra Ray among his friends, he was a public intellectual whose inner life was actuated by deep sense of curiosity about everything.

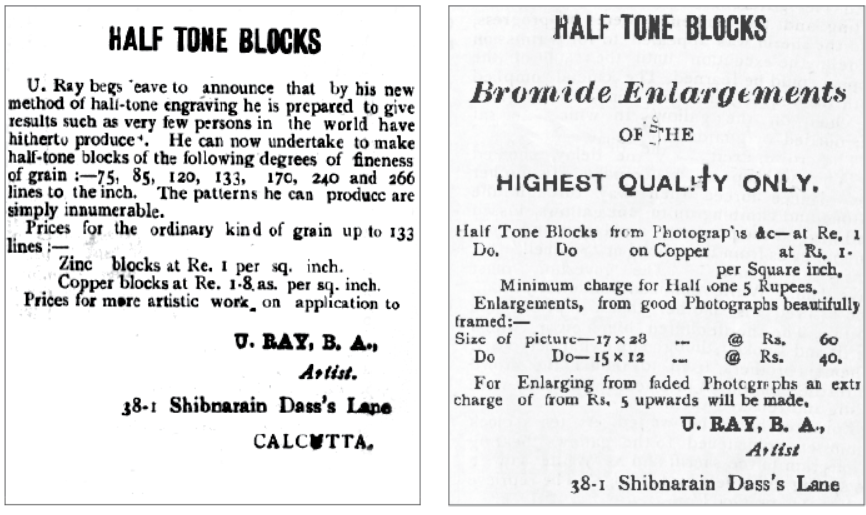

Upendrakishore began his writing career in the mid-1880s when he was a student. He mainly wrote for a young audience and also illustrated his own stories. By the mid-1890s, he was dissatisfied with the quality of printing of his illustrations and decided to experiment with the latest techniques of printing illustrations. He ordered a process camera and other equipment necessary to produce half-tone blocks. He went into business as 'U. Ray, B. A., Artist'. Besides half-tone blocks, he also offered "bromide enlargements of the highest quality only." In 1897, he was confident enough to assert in his advertisements in the Amrita Bazar Patrika that “he is prepared to give results such as very few persons in the world have hitherto produced.” His expertise in block-making drew clients from all over India; it could be Natesan & Co of Madras, the prolific nationalist publisher or the Raja of Aundh who wanted to print his own paintings.

Upendrakishore Ray Chaudhuri (1863–1915)

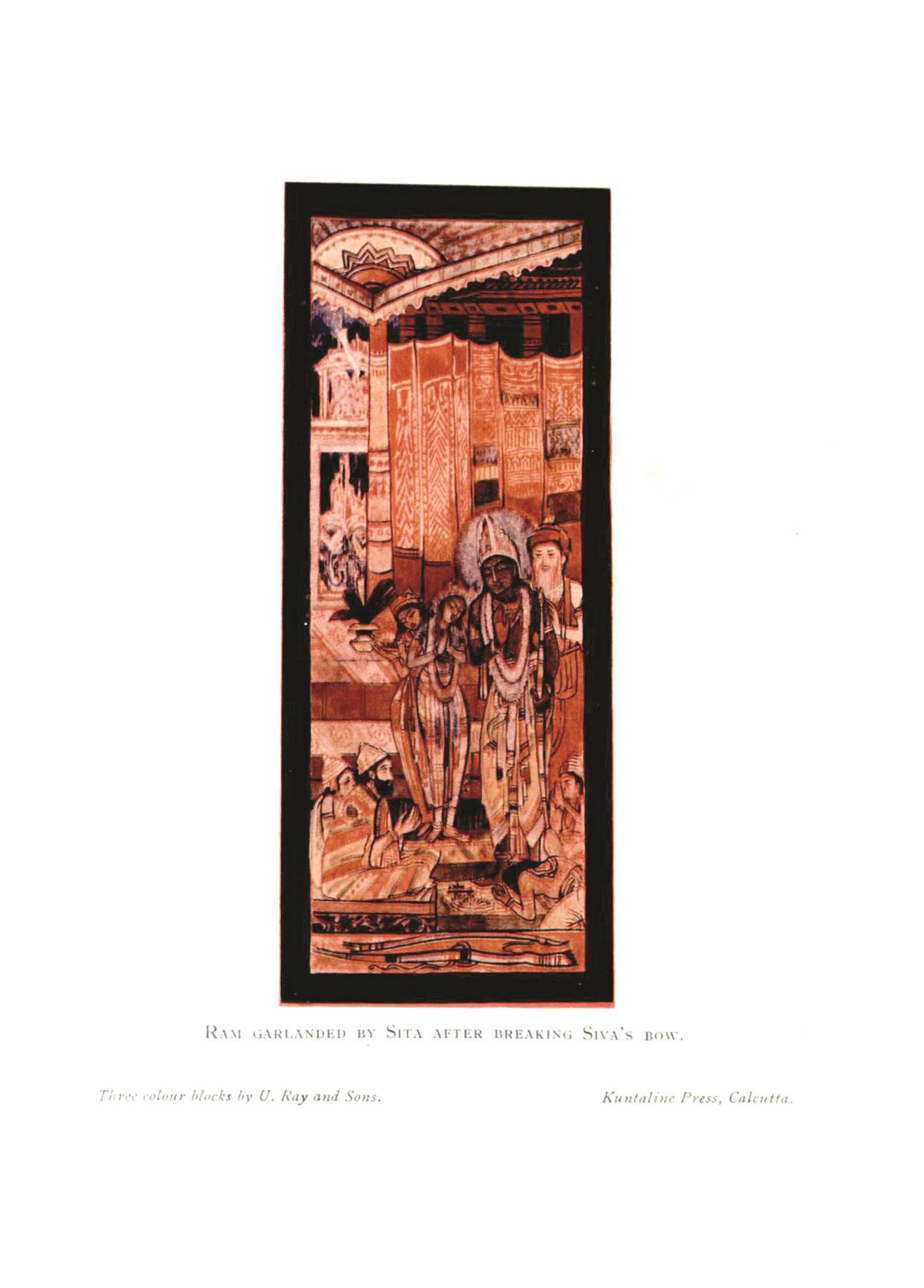

In Calcutta, his most important client was Ramananda Chatterjee. When Chatterjee was the editor of the magazine Pradip in 1897–1900, he commissioned U Ray to produce half-tone blocks of photographs and paintings. After Chatterjee started the long-lived journals, Prabasi (in 1901 in Bengali) and The Modern Review (in 1907), three-colour illustrations by U Ray appeared in most issues. These illustrations were so popular that they were also sold separately under the title Chatterjee’s Picture Albums.

As the swadeshi movement swept Bengal from 1905, some members of the Ray family, already involved in the nationalist movement, adopted an austere swadeshi lifestyle. Business ventures like that of Upendrakishore’s were seen as prototypes for what an Indian-owned enterprise should be. However, there were others who felt that half-tone photography, though the latest in terms of technology, could not reproduce the tones and subtleties of Indian painting. They would rather order colour prints made from woodblocks in Japan or photogravures from London.

By 1910, Upendrakishore was ready to induct his sons into the business; he also added a printing department. The firm acquired a new name: U Ray and Sons, Printers and Block Makers. It focused on printing and publishing books written by Ray and his extended family. In 1911, the press moved to a custom-designed building which also housed the Ray family. The only description of the printing press is by Satyajit Ray; relying on his memory as a five-year-old boy, he evokes the interiors of 100, Garpar Road, as it was in 1925–26.

It was not just a house, but a printing press as well. My grandfather, Upendrakishore, had designed the house himself, but was able to live in it for just four years. … High on the wall in front of our house, ‘U RAY & SONS, PRINTERS AND BLOCK MAKERS’, was written in large letters.

To get to the press, one had to pass through the gate, go past chowkidar Hanuman Mishir’s room and up a flight of steps. A huge door marked the entrance to the press. The press was on the ground floor; the rooms for block-making and typesetting were directly above it, on the first floor. We lived in the rear of the house. A little lane to the left led to the entrance door of the residential portion of the house. The door opened to a flight of stairs. Those who had business in the press, turned left as they came up the stairs; and our friends and relatives turned right to go into the portion where we lived. The door on the left led to the block-making department, and the one on the right led to the drawing room.

I usually visited the press in the afternoon. The first thing one saw on entering were the compositors who sat in rows, bent over their type-cases with different compartments, picking out letters and arranging them in rows to match the text. … I used to walk past them and go to the back of the room. … In the middle of the room stood the huge process camera. One man had learnt to handle it extremely well. It was Ramdaheen. He came from Bihar, and had originally started work as a mere bearer. My grandfather had taught him how to operate the camera.

Advertisements by U Ray, Amrita Bazar Patrika, 6 July 1897 and 7 July 1897

The science behind the craft

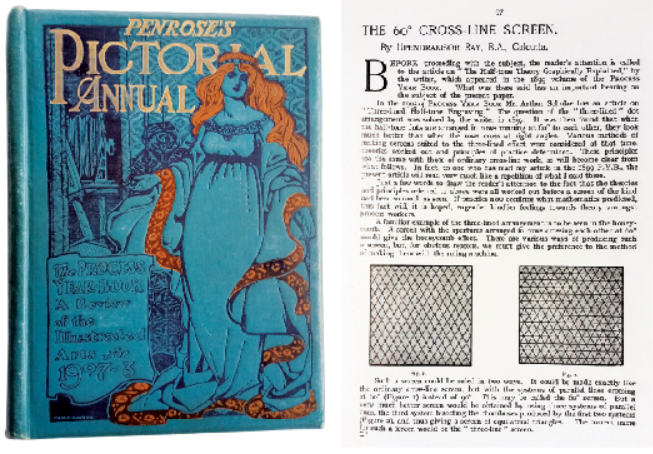

Upendrakishore’s focus in his research on half-tone photography was to make it easier for practitioners like Ramdaheen by providing them with simple tools to aid their work and minimise the use of discretion and rules of thumb. Unlike most other innovators, Upendrakishore tried to understand the scientific theory behind the variations in the results he obtained from the process camera. His was not mere idle speculation but an endeavour to improve practice by using the underlying principles. Most of his writings on this subject were published between 1897 and 1912 in The Process Yearbook, a journal which later acquired the additional title Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, by which it became famous.

Photo-mechanical processes for converting images into printing surfaces involve multiple steps with variables at every stage of the process. The original image, continuous in tone, had to be broken up into components – dots and lines – to create a printing surface, harkening back to the stippling and grooving techniques used in engraving images on metal in the eighteenth century. From the 1880s, this conversion, known as the half-tone process, was largely done by photographing the image with a process camera through a screen to create a negative on a sensitised metal surface. After the metal negative had been developed, it was subjected to a chemical etching process which would produce a printing surface in relief.

For finer finishes, the etching processes would have to be repeated up to four times. The finished half-tone block was then mounted on a larger piece of metal and could now be used to print illustrations on letterpress printing machines. It could be mounted on its own or locked into a chase along with textual matter composed by type.

Upendrakishore’s research focussed on the photographic method rather than the etching process. The key influencer of results was the screen which was generally two pieces of glass with rulings of parallel lines and glued tight at right angles to each other. The density of the ruling, generally expressed as number of lines per inch, the screen’s placement relative to the image and the negative, and the shape of the apertures on the screen influenced the quality of the negative.

For over a decade, “an article from the classical pen of Mr. U. Ray, B. A, on the principles of the half-tone process” appeared in most issues of Penrose’s Pictorial Annual. They contained in-depth discussions on the principles of half-tone photography; Upendrakishore advocated a deeper understanding of the theories so that printers could “act in strict accordance with the knowledge thus acquired.” He was of the opinion “that the half-tone theory is nobody’s private property.”

Based on his theoretical understanding of the process, Upendrakishore was able to propose solutions to specific problems faced by half-tone photographers. Perhaps his most significant contribution to the process was the design of the screen adjustment indicator which accurately determined the distance at which the screen had to be placed from the image so that “the element of uncertainty [is] eliminated from the most vital portion of the work.”

He also suggested a modification to the traditional screen in 1897: the ‘60º Cross-Line Screen’ in which the lines intersected at 60º to each other and formed a rhombus pattern. He was informed by screen manufacturers that it was technically impossible to produce this screen. A few years later, he was shocked to discover that one of his correspondents had patented the very same idea. He stoically remarked: “To the craft it matters little who gets the credit for a particular invention.”

By 1911, when the firm moved to 100, Garpar Road, Upendrakishore was ready to hand over the baton to the next generation. Upendrakishore’s eldest son, Sukumar Ray (1887–1923), was cast in his father’s mould. His work as a writer and illustrator continues to be celebrated and overshadows his work as a technologist. During his teenage years, he would have been a constant presence in the printing press as an unofficial apprentice.

Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, cover of the 1907-8 issue and an extract from an article by U Ray

After completing his graduation (double honours in physics and chemistry) in 1906, Sukumar joined the business and seems to have become as much a technical expert as his father. In 1911–13, he spent two years in England studying printing technology in London and Manchester. Though he went on a student scholarship, he was already an expert in many aspects of printing and collaborated with the leading process technologists, including the editors of Penrose’s Pictorial Annual, in their assignments.

In England, Sukumar hoped to undertake research on the photo-mechanical process; writing to his father on 20 September 1912, he outlined his plans: “I’ve got an idea I want to do some systematic research on, if possible – what I have in mind is the difference in the gradation and etching characteristics of a picture for various kinds of dot, and whether one can demonstrate these quantitatively – that would be worthwhile. Additionally, I hope to work out some kind of process of printing with the gelatin pigment of the Woodbury type from the intaglio halftone block. It strikes me that the result could be as good as the finest photogravure.”

He complained about not getting access to equipment and being swamped by unnecessary coursework but he seems to have benefited from his stint abroad: not only could he visit the best printing firms in Europe, he could also build connections with leading process researchers. After returning to India, Sukumar contributed essays to Penrose’s Pictorial Annual and the British Journal of Photography. He was not as diffident as his father; for example, he proposed the ‘Sukumar Ray’s Method’ for setting screen distance in half-tone photography.

Illustration in The Modern Review (1912) printed using blocks made by U Ray and Sons

Losing Focus

In April 1913, Upendrakishore started Sandesh, a monthly magazine for children in Bengali. It contained illustrations and stories by Upendrakishore and other members of the Ray family. It proved immensely popular and is perhaps the most iconic imprint of the press. Upendrakishore’s untimely death in December 1915 was universally mourned in Bengal. The obituarist in The Bengalee (22 December 1915) predicted Upendrakishore’s future fame based on his writings and illustrations; he also highlighted his work on print technology:

Alone and single-handed, he worked with very limited resources for years together undaunted by various obstacles and disappointments until he was able not only to produce high-class Half-tone blocks but to improve the system of Process work by more than one important original inventions—inventions which found ready welcome and acceptance in the Process-Work world of the United Kingdom where he was considered an authority on the subject.

Sukumar Ray took over the management of U Ray and Sons and the editorship of Sandesh from January 1916. This was also the period when he did much of the writing and illustrations for which he would become famous. After Sukumar Ray’s early death in September 1923, his younger brothers, Subinay and Subimal, managed the press and its publishing activities.

From as early as 1920, the affairs of U Ray and Sons were financially straitened and the brothers had pledged its assets to raise a loan of INR 16,100 from Surendra Nath Dey. Its working capital was funded with a loan from the Co-operative Hindusthan Bank Limited. By August 1925, the distress was so acute that they had to raise emergency funds from one Uday Chand Daga. As the business unravelled, the Ray brothers declared bankruptcy and moved out of the premises at 100, Garpar Road in January 1927.

Illustration from Tuntunir Boi (1910) by Upendrakishore Ray Chaudhuri

The three creditors scrambled to recover as much money as they could by claiming the assets of the company. Within a week, the bank had disposed some of the assets of the press which included “furniture of various kinds, 50 reams of printing and writing paper (valued INR 800), 1000-lbs. of types (valued INR 2,000), accessories and borders (valued INR 1,000), photographic chemicals, 60 sets of tricolour blocks, and 300 half-tone blocks (valued INR 3,300), 15 dozens of thermometers (valued INR 180), besides the Harrild's Rapid demi-cylinder machine (valued INR 6,000) and printing inks and other accessories” for a paltry sum of INR 4,425 to Indian Soap Company, which had an in-house press to print labels and make cartons for its products.

The other creditors questioned the propriety of this fire sale and the matter went into litigation where the court observed that “the procedure adopted by the bank was irregular in the extreme; no proper publicity was given to the intended sale, no sufficient inquiry was made to ascertain the then market-value; no real effort was made to sell at the highest available price.”

By the time the Calcutta High Court gave its final ruling on various appeals in July 1931, the Rays had lost not just the business but also their primary residence which was located in the same premises as the printing press.

The goodwill of U Ray and Sons, including the copyright to its publications and the magazine Sandesh, was also auctioned off. All the family had left were memories. Nearly fifty-five years after the family’s departure from 100, Garpar Road, Satyajit Ray recalled the printing press in his childhood memoir: “Even today, if I catch a whiff of turpentine, a picture of U. Ray and Sons’ block-making department floats before my eye.”

References

Archival records from Private Collection of Upendrakishore Ray Chowdhury's Family, Kolkata. British Library, Endangered Archives Programme EAP1104-7.

Amrita Bazar Patrika (6 July 1897 and 7 July 1897).

‘Co-Operative Hindusthan Bank Ltd. And Ors vs Surendra Nath Dey And Ors. on 22 July, 1931.’ All India Reporter, Calcutta Section, 1932 [AIR1932CAL524].

Guha-Thakurta, Tapati. The making of a new ‘Indian’ art: Artists, Aesthetics and Nationalism in Bengal, c. 1850-1920. Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Ray, Satyajit. Childhood Days. Translated by Bijoya Ray. Delhi: Penguin, 1998.

Ray, Sukumar. ‘Selected Letters of Sukumar Ray.’ Foreword by Satyajit Ray. Translated with an introduction and notes by Andrew Robinson. South Asia Research, 7:2 (November 1987): 169–236.

Ray, Sukumar. Sukumar Sahitya Somogro. Volume 3. Edited by Satyajit Ray. Kolkata: Ananda, 1989.

Raychowdhury, Upendrakishore. Essays on Half-Tone Photography. Kolkata: Jadavpur University, 2014.

Robinson, Andrew. Satyajit Ray: The Inner Eye. London/New York: I B Tauris, 2004.

‘The Late Mr. U. Ray.’ The Modern Review 19:1 (January 1916).

‘U. Ray Dead: A Remarkable Career.’ The Bengalee (22 December 1915).

See All

See All