Print History: Titaghur Paper Mills - Paper Manufacturing in the 1890s

A forgotten Gujarati travelogue provides a glimpse into the workings of the first modern paper manufacturing facility in India during its early years

30 Nov 2022 | By Murali Ranganathan

As India struggled to rebuild its industries which had been decimated by a century of predatory colonialism, factories using European technology began mushrooming across the length and breadth of the country in the last decades of the nineteenth century. The cotton textile industry, which India had globally dominated for two millennia, was at the forefront of this revival. But other industries were not far behind: mining, foundries, glass, chemicals and many other sectors also began to attract investment from private capital, both Indian and foreign.

The printing industry, which had seen dramatic growth after 1860, was largely dependent on imported paper for its needs in this period.

Though India has a paper manufacturing tradition going back to at least the fourteenth century, the cost of indigenous handmade paper, which by its very manufacturing process was of a high quality, rendered it too expensive for most printing applications. Most printing presses imported their paper from Europe. The Indian paper industry, which had manufacturing centres all across the country, was also in a state of decay. Given its antiquated technology, it could not cope with the demands of a rapidly industrialising nation. The time was ripe for modern paper mills, which had been designed in 1799 in France, to make an appearance in India.

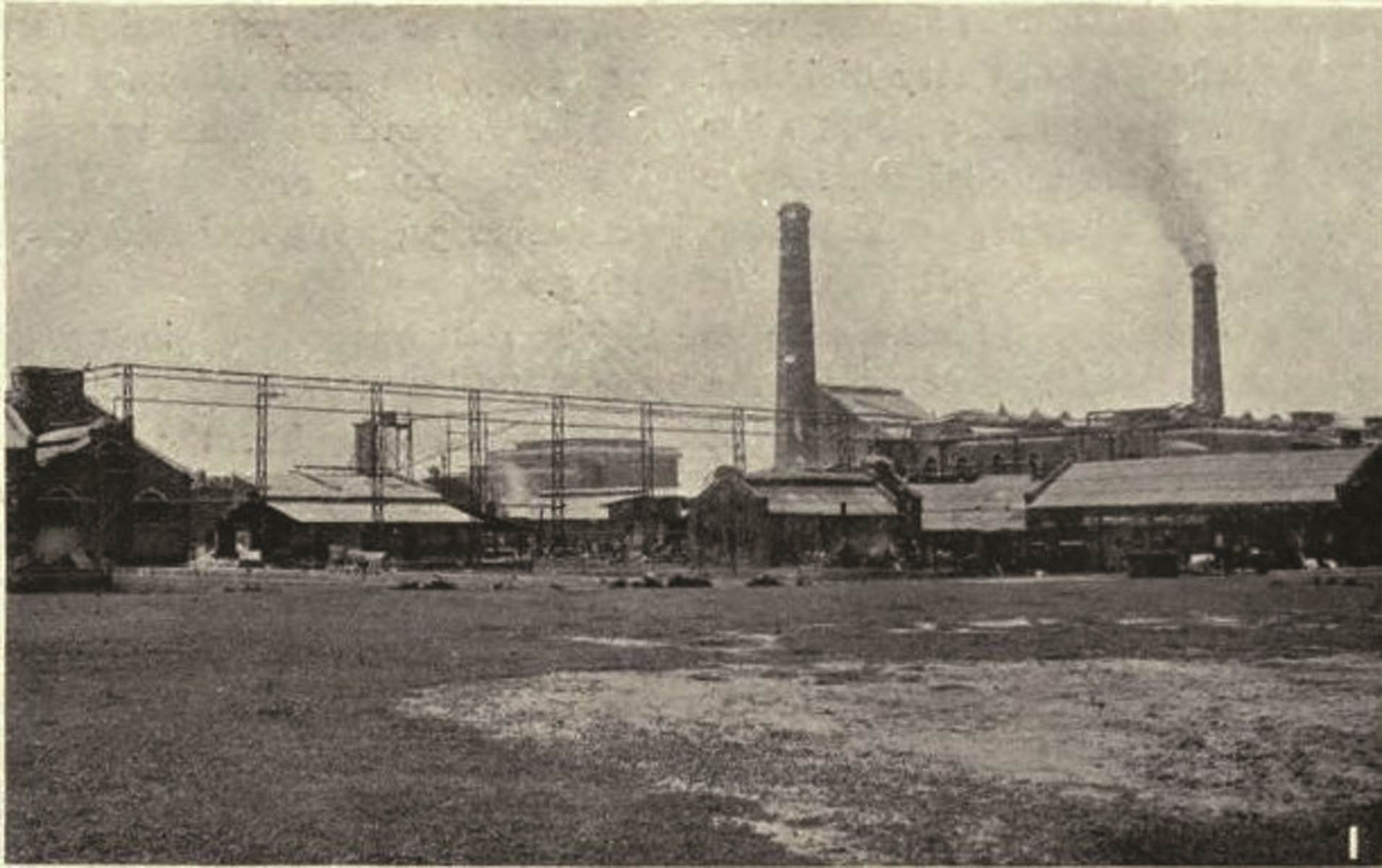

A bird’s eye view of the Titaghur Paper Mills

Industrial tourism

Industrial tourism was all the vogue in India during the final decades of the nineteenth century. Urban biographies and guidebooks from that era exhorted their readers to visit textile mills, printing presses, flour mills, workshops and suchlike at every opportunity. For instance, in Hindustanma Musafari (a Gujarati travelogue published in 1871), the travellers, on a pan-India journey, made a special detour to Ranigunj Coalfields to observe deep shaft mining. Visitors to Bombay were urged to inspect its sprawling textile mills and the impressive machinery at the Times Press. The classic urban biography Govind Narayan’s Mumbai, originally published in 1863 in Marathi, suggests a visit to a paper mill:

Workshops to manufacture paper in the English fashion were set up in Mumbai about eight to ten years ago. They turned out to be an expensive proposition as the output was meagre and of low quality. This led to their closure. This activity has however been revived and a workshop has been established in Girgaum. The large machines and the huge wooden vessels for processing rags are worth a look. There is also a steam-powered machine. Thick paper in the Ahmedabadi fashion is also produced in Mumbai. There is also a paper factory in Mahim which produces ordinary paper of the English type.

Continuing in the same tradition, the Gujarati travelogue Maro Pravas or My Travels by Manekji Cursetji Thanewalla is largely concerned with describing visits to industrial sites. Published privately in 1892, this brief travelogue written by a young man provides a glimpse of industrial India on the cusp of modernity. In July 1891, Thanewalla had just completed his mechanical engineering course at the Victoria Jubilee Technical Institute (VJTI) in Bombay and was awaiting his examination results. He set off on a whistle-stop tour of India and Burma with five friends or classmates.

Like him, they were Parsis and could expect hospitality from their compatriots at every place they visited. In most cities, they visited many of the popular historical sites but never missed an opportunity to visit factories and workshops. As they were recent engineering graduates, their curiosity about all things mechanical can easily be fathomed. Their first stop was the city of Calcutta which had a direct train connection from Bombay. About two hundred Parsis lived in Calcutta at this time; most of them were engaged in business or employed in commercial firms. The travellers already had connections with members of the Parsi community in Calcutta and were soon able to identify the places which they wanted to visit.

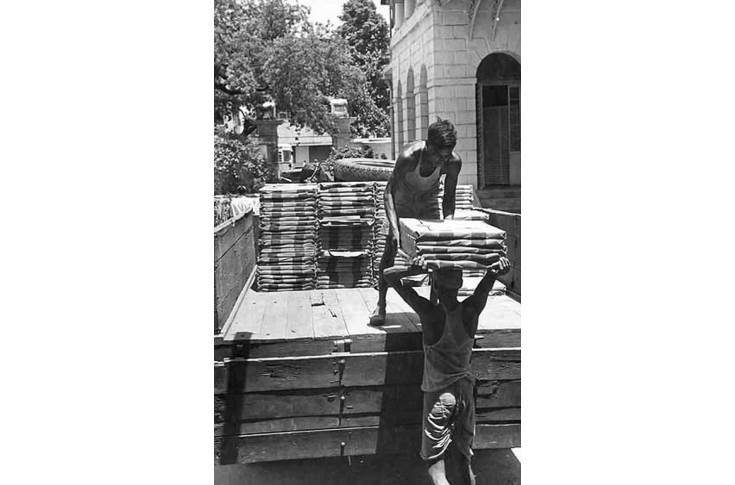

The delivery of paper from Titaghur Paper Mills to the Baptist Mission Press, Calcutta (Source: wmcary.edu)

Titaghur Paper Mills

In the 1890s, Calcutta was perhaps the most industrialised of all Indian cities. The Indian jute industry was concentrated in Calcutta and many of the largest engineering firms had their workshops in that city. It was the epicentre of the mining sector. It was still the print capital of India, a distinction it had held for nearly a century from the 1790s. The first experiments in manufacturing paper using a mechanised process was also made in Serampore near Calcutta. Probably started in the 1830s, the paper mill was famous for its white paper of middling quality known as ‘Serampore Paper’. It was subsequently designated as Bally Paper Mills and survived until the end of the century without any upgradation or investment.

Calcutta was also the city where the first large scale paper manufacturing plant was built in the 1880s. It was located on the banks of the river Hooghly at Titaghur, just north of the city and a short train ride away. The Titaghur Paper Mills Co. Ltd. was set up by Reinhold & Co in 1882 but was soon taken over by F W Heilgers & Co who controlled a number of industrial concerns. The mill commenced operations in 1884. After overcoming a few teething troubles, the plant was able to supply good quality paper at a price cheaper than that of imported paper of a lower quality. The budding Parsi engineers visited this plant, perhaps at the invitation of their community brethren who were working in the paper mill in a supervisory role. Thanewalla describes this visit in his travelogue:

Calcutta, Saturday, 19 September 1891

[After visiting the waterworks at Barrackpore], we went to see the paper mill at Titaghur. This mill is under the direction of a German named Heilgers. The capital for the paper mill was raised from shareholders who paid Rs. 100 per share. The price of each share has now increased to Rs. 150. The mill was erected at a cost of seven lakhs of rupees. It works night and day except on Saturdays when it shuts at ten in the night. It is not as if the men who work during the day also work at night; instead a completely different team takes over from them. The group that works during the day for a week has to work the night shift in the following week. Two Parsi brothers are employed in this mill. Their names are Mr. Pestonji N. Sorabji and Mr. Byramji N. Sorabji. They also have to work in shifts. When one brother is assigned the day shift, the other works the night shift. The mill employs about 700 people. Mr Pestonji gave us a tour of the mill and showed us the process by which paper is made.

Thanewalla then goes on to describe the manufacturing process at the paper mill. The description is rather sketchy and Thanewalla does not get into the details of the workings of the paper manufacturing machine.

I beg leave to provide a very brief account of the method by which paper is made in this mill. Firstly, a very large circular vessel is filled with dirty rags, pieces of cloth, bits of hemp rope and other articles of a similar description. Steam is passed through this vessel at very high pressure to soften the material and reduce it to a pulpy state. The rags are softened in this vessel for nearly four hours. Once this process is completed, the pulp is removed from this large vessel and transferred to smaller containers which are open at the top and rotate slowly on a central pivot. Water and alum are added to these containers to clean and bleach the pulp rendering it as white as milk. As the container rotates continuously, the pulp gets uniformly mixed. From here, the mixture is transferred to a roller which squeezes out some of the water. It is then taken to a papermaking loom which is similar to a textile loom. The mixture is poured into this loom which converts it into a long stretch of paper, about 40 inches in width and 100 yards in length. The freshly made paper is rolled onto a spindle which also rotates slowly.

Once the roll is full, it is transferred to another department where the paper is cut into the required sizes. This mill has signed a contract to exclusively cater to the needs of government and cannot take orders from traders or other customers. Since the requirements of government are very large, the mill operates day and night to meet its contractual obligations.

The travellers stayed overnight at Titaghur with their new Parsi friends and seem to have had a jolly time. The Sorabji brothers played a practical joke on them and caused them to miss their train to Calcutta the following morning.

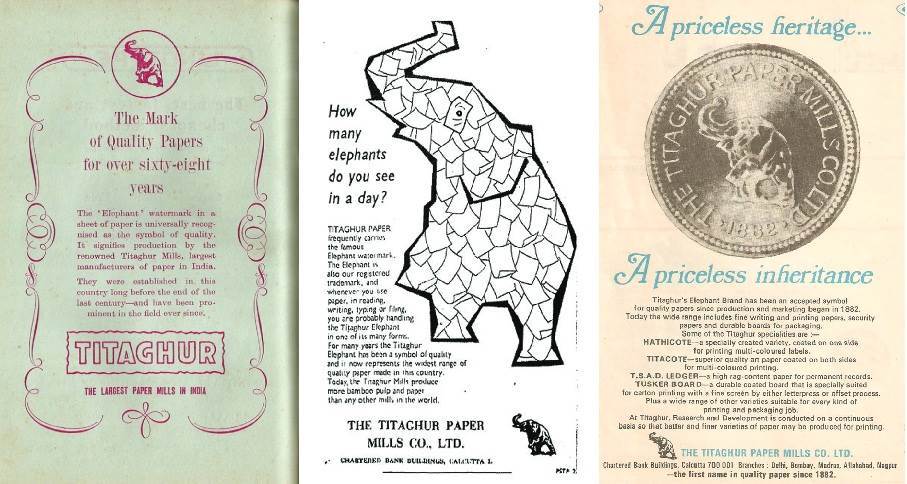

Advertisements for the Titaghur Paper Mills from the 1950s and 1960s

The Titaghur Paper Mills went on to become synonymous with paper in India. By 1910, it had taken over Imperial Paper Mills and Bally Paper Mills, both in the vicinity of Calcutta, to become the largest paper factory in India. The paper manufacturing industry also developed all across India and some of the leading mills of this period included the Girgaum Paper Mills (Bombay), Scindia Paper Mills (Gwalior), Reay Paper Mills (Pune), Bengal Paper Mills (Ranigunj), and the Upper India Paper Mills (Lucknow). An industrial gazetteer from 1917 (Bengal and Assam, Behar and Orissa: their history, people, commerce, and industrial resources) provides an overview of the operations of the Titaghur Paper Mills.

The company are owners of two mills, situated at Titaghur and Kankinara, which are 14 miles and 25 miles distant from Calcutta respectively, and each of these has four paper-making machines. … The machinery at Titaghur is now driven by electricity, the power being derived from steam turbines, while at Kankinara the main drive is accomplished by one triple-expansion 1,100 h.p. engine with rope drives throughout. … The mills not only have the advantage of an unfailing supply of water from the River Hooghly, upon whose bank they are erected, but they have, further, sidings upon the Eastern Bengal Railway system and river jetties to facilitate the dispatch of goods. Each property has excellent workshops for mechanics, blacksmiths, joiners, and plumbers; the shops contain an unlimited supply of tools of the latest approved pattern, and the staff of trained work people are under the constant supervision of four European superintendents. The annual output of the two mills is about 19,000 tons, and the products, which are of admirable quality, comprise papers known as engine and tub-sized cream wove, cream laid, bank posts, azure laid, white and toned printing, coloured printing, white and brown cartridges, Badami, Manila, and glazed art.

The Titaghur Paper Mills sold its paper under the ‘Elephant’ brand which soon became synonymous with paper in India. It was also used as a watermark on paper manufactured by the company. Its clients included provincial governments, railways, the princely states and many of the major printing presses. Though its management was largely European, its products — manufactured in India using Indian raw material and labour — were considered ‘Swadeshi’ and marketed as such by its dealers, in preference to imported paper.

Epilogue

From Calcutta, Thanewalla and his friends went to Rangoon, another city where the Parsis had built a prominent presence. Coming back to Calcutta, they went to Darjeeling for a short stay. They then set off on a tour of north India visiting Allahabad, Kanpur, Lucknow, Agra, Mathura, Delhi and Jaipur. After a two-month tour, Thanewalla returned to Bombay by way of Baroda in November 1891, just in time to receive his Licentiate in Mechanical Engineering with a First Class Full Technological Certificate. He continued his education at VJTI and received his Licentiate in Textile Manufacture in 1893. He must have worked in the engineering and textile sector for a decade and more before becoming an entrepreneur. In 1906, he set himself up as an ‘Engineer & Contractor’ and founded Thanewala & Co. His travelogue, Maro Pravas, written to amuse his family and friends, did not make it to the footnotes of the Gujarati travel canon and was completely forgotten until its recent discovery.

For over a century, the mills at Titaghur continued to manufacture paper before finally winding down its operations in the 1990s. The machinery and other paraphernalia still survive on the original site which would be an ideal location for any commemorative museum of print and paper in eastern India.

References

- Bengal and Assam, Behar and Orissa: their history, people, commerce, and industrial resources, compiled by Somerset Playne (1917)

- Govind Narayan’s Mumbai: An Urban Biography from 1863, edited and translated by Murali Ranganathan (2007)

- The advancement of industry; being a study of certain manufacturing industries in India with suggestions for their development, Henry Hemantakumar Ghosh (1910)

See All

See All