Print History: Vakil & Sons - A Story in Numbers

Rarely does one chance upon an uninterrupted series of annual financial statements going back seventy-five years in the Indian print world. The numbers tell a starker story than words

26 Jan 2024 | By Murali Ranganathan

The Ballard Estate business district of Bombay, laid out in the 1910s, abutted not only the bustling commercial area of the historic Fort of Bombay but also its docks. At one corner of the triangle-shaped precinct is the Ballard Pier where passenger ships called until the 1970s. Its tree-lined streets and the uniform faux Renaissance architectural style of its buildings imbue it with a distinct urban texture. Strolling down its principal axis, Sprott Road (now Seewoosagur Ramgoolam Road), one can spot numerous business establishments which have been in existence for a century or thereabouts. At its head is the Grand Hotel and adjacent to it is Karfule, a petrol pump from the 1930s. Further ahead are two iconic restaurants of a similar vintage with distinctive cuisines: National Hindu (Udupi) and Britannia (Irani) at Wakefield House. Between them was Pathé Building, housing the eponymous pioneering film and phonography company. A

nd round the corner is Hamilton Photo Studio, founded in 1928. Nestled among all these iconic brands is Vakils House (earlier Narandas Building), the site of the printing establishment known as Vakil & Sons Limited. Vakils is perhaps the only Bombay printing press from the pre-1947 era to have maintained a business archive. Besides a couple of printing machines from the 1930s, the archive includes photographs, printing samples, reminiscences by retired employees, memoirs written by the Mehta family and the annual financial reports which go back to 1946–47, the year in which the company was incorporated. But the history of Vakils goes back to twenty-five years earlier.

.jpg)

Vakils operations team 1950, (from left) Moses, Bindery Supervisor; JR Parikh, Chief Accountant; Luis Pereira, Chief Compositor; Kantilal U Mehta, Managing Director; Isaac N Issac, Works Manager; Shankarprasad Desai, Proofreader

The Early Years (1920–46)

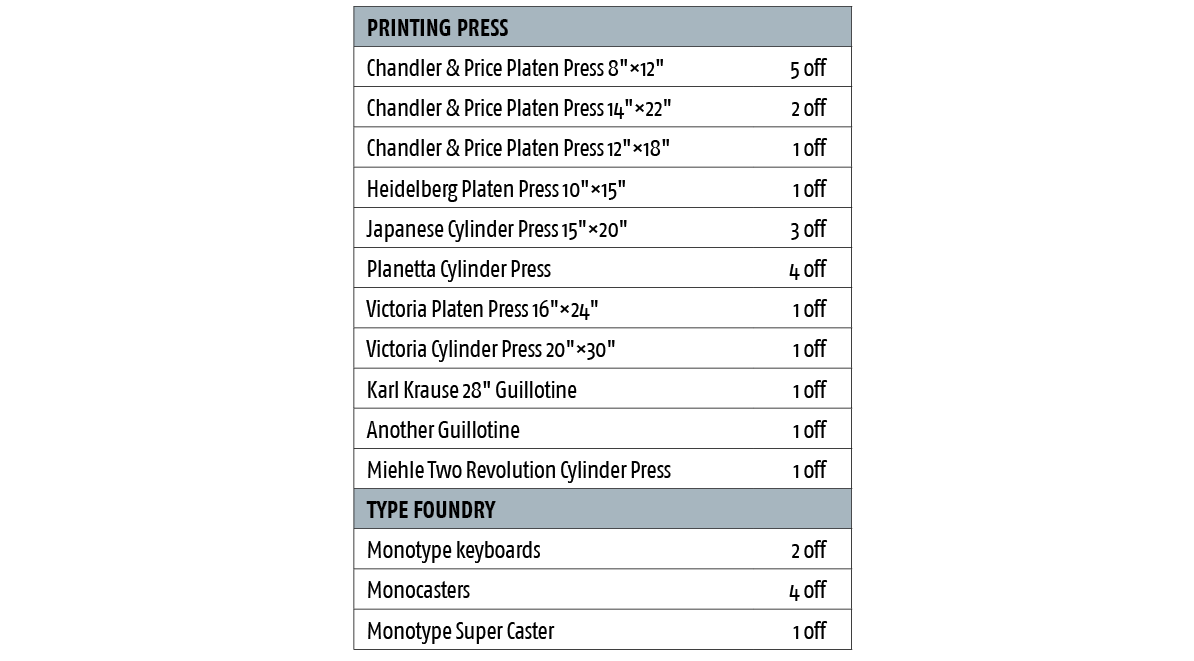

Founded on 20 June 1920 by the Vakil brothers, Erachshaw and Ruttonshaw, in partnership with K R Sudder, Vakils began life as a stationery shop in Tamarind Lane before it diversified into printing. The following year it moved to premises at Elphinstone Circle, an area studded with printing offices. In the initial years, it had one Chandler & Price 8"×12" platen printing machine and a Karl Krause 28" guillotine. With Sudder handling marketing activities (then known as canvassing), the printing business picked up. More investments in printing machinery were called for which the Vakil brothers were loath to make. Sudder, therefore, acquired their share and converted the partnership into a sole proprietorship around 1930. The printing business moved to the first floor of Wakefield House, next to Vakils House in Ballard Estate. As the demand for business premises continued to remain sluggish in Ballard Estate, Vakils could shift into more spacious premises next door. It grew into a substantial job printing press and employed about sixty people in the mid-1930s. An impressive assortment of print machinery dotted the Vakils shop-floor.

Vakils had clients with a variety of profiles: large corporate companies, magazine and book publishers, and educational institutions. Its corporate clients were Dunlop Rubber Co and General Motors, besides Pioneer Magnesia Works and Central Bank for whom it printed stationery, annual reports and house magazines. It printed magazines such as Trademark Journal and Cinevoice, the leading English film monthly of its time. It also accepted confidential assignments to print question papers at very short notice from St. Xavier’s College and Bharda New High School.

When the German consulate on the first floor of Vakils House shuttered down in 1940 soon after the Second World War started, Vakils acquired the premises they had occupied. Sudder started a type foundry by acquiring second-hand machinery from a newspaper printing press. Named the Liberty Type Foundry, this new line of business also thrived.

In the mid-40s, Sudder decided to exit the printing business; perhaps he wanted to focus on his block engraving business, named Graphic Art Engraving Co, which was housed across the road from Vakils. This business, later known as Commercial Art Engravers (ComArt), became one of the leading engravers of Bombay. Sudder first sold one half share of the business in 1944 to Neville Mistry and then the other half to him in the following year. The new proprietor also a ran a stevedore and ship chandler business, Trinity Stores & Supply Co, which he moved to Vakils House.

No financial statements from this period have survived but from later evidence, one can conclude that the business was on an even keel. Its annual turnover was around Rs 350,000 and its assets including plant and machinery were also worth Rs 350,000. Except for Sudder, none of its owners had any experience in the printing industry and relied on the expertise of their employees. Vakils had a trained and committed management team that reflected the cosmopolitan nature of the city. Its Works Manager, perhaps the key to its operations, was Isaac N Isaac. The chief compositor was Luis Pereira while its principal proofreader was Shankarprasad Desai, who could handle texts in English, Gujarati and Hindi. The bindery was headed by Moses. The chief accountant was J R Parikh.

Printing Infrastructure, mid-1940s

Going corporate (1946–50)

With the impending departure of the British, who dominated the upper end of the printing sector, there were bound to be opportunities for Indian printers. The printing business needed substantial investments to keep pace with the growing demands of the market and remain competitive. Mistry restructured the business from the proprietorship to a company to raise funds from investors. The goodwill of the business was valued at Rs 68,000 and transferred to a company incorporated on 31 July 1946 with a capital of Rs 500,000 (divided into 1000 shares of Rs 500 each). Though the Vakils had exited the business two decades ago, the company was named Vakil & Sons Limited. The new investors included the Marker and Shah families, both of whom were stockbrokers. They nominated members to the board of directors while Neville Mistry became the Managing Director.

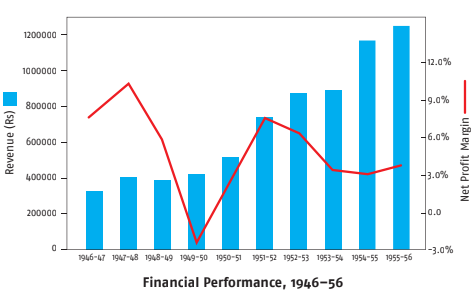

The annual financial statements of Vakils for the ten years from 1946–47 to 1955–56 tell the story of the transition of Vakils from a proprietorship to a professionally managed printing company. The financial year ran from 1 July to 30 June. All the currency figures were triple-barrelled (for example, 4567-12-3), signifying rupees, annas (16 to the rupee) and paise (12 to the anna). The documents list expenses that one would not encounter in a modern profit and loss statement such as ‘Cartage and Coolie Charges’ and ‘Daily Wages’. And terms which one might encounter only within a printing company: ‘Hire of Matrices’, ‘Type and Metal’, ‘Paper’ and ‘Ink’.

In 1946–47, the sales revenue of Vakils was Rs 330,391 (for an eleven-month period). The profit margin was a healthy 8 %. Sales did not increase for the next three years and hovered around Rs 400,000. On the other hand, profitability dipped in successive years before the company posted a loss on 1949–50. The directors had already forecast the loss in the previous year; it was attributed “to very heavy competition in the field, and lower production, in spite of higher wages.” Perhaps Mistry and the other shareholders were not interested in getting their hands dirty on the printing shop floor. By mid-1948, Neville Mistry seemed to have decided to exit the company.

When the business was restructured into a company, equity capital of Rs 500,000 was raised. With revenues of less than Rs 400,000 for the next four years, the business was highly overcapitalised. No debt funding was availed, not even for working capital. Even though the business had potential for growth, hardly any investments were made for printing infrastructure in the first five years. In 1949–50, even though the directors recommended the purchase of “at least one Double-Demy machine to carry on the work more economically and be able to stand against the heavy competition of other presses,” they complained about the lack of funds. On the other hand, they had been declaring dividends in the previous three years, including the year the company made a loss. In the period leading to his exit from the company, Mistry had run down the balance sheet by reducing the inventory, aggressively recovering money from debtors, making dividend payments and putting a moratorium on all capital spending.

Chandler & Price Plate Press, 1930s vintage

Between December 1948 and August 1949, Mistry gradually sold his shares to the Mehta family who acquired about a one-third share of the company. The Mehtas, who had South African antecedents, included the patriarch Umiashankar Mehta and his five sons. Kantilal U Mehta was the Managing Director during 1949–51 before passing on the baton to his brother Gunvantrai Mehta. When further shares in Vakil & Sons were offered for sale in the early 1950s, the Mehtas induced their clansmen from Morvi and Porbandar to purchase them, thus consolidating their control over the affairs of the company.

A Time for Change (1950–56)

When the Mehtas took over the management of Vakils in 1950, Vakils had been in existence for three decades and could command a wealth of resources. It was located in a prime location of Bombay in close proximity to many corporate clients including some of the leading book publishers of Bombay such as D B Taraporevala & Co and New Book Co. The Mehtas retained all the key employees who headed the various departments. Their relations with the directors representing the Marker and Shah families remained cordial and Lily Marker served as the chairperson of the board of directors until the 1960s. The Shah brothers, Jayantilal Chimanlal and Manubhai Chimanlal, continued as directors of Vakils even after their shareholding had been reduced substantially.

From 1950–51, the first full year in which the Mehtas were in control, sales revenue increased at a steady rate. It had reached Rs 12,63,121 by 1955–56, reflecting a compounded annual growth rate of 20% during the six-year period. Much of the credit for this increase devolved on the Managing Director as noted in the annual report for 1955–56:

During the year under review, your Managing Director, Shri G. U. Mehta visited the International Printing Machinery and Allied Trades Exhibition in London and visited several other countries in Europe to study the new methods of printing. The better results of working are to a very great extent due to the experience gained by him during his trip.

Most of the revenue came from printing operations. In the initial years, the type foundry also contributed a small share but after 1950, it was negligible. The Mehtas introduced a new business in 1950: blockmaking for printing illustrations. This business line became a fairly significant contributor to revenues by 1955–56, so much so that Vakils positioned itself as “Specialists in Colour Printing and Blockmaking.” However, profit margins were very variable. It was also a period of transition in management which might have created a little turmoil in the operations. Net profit margins averaged 4.4% which was perhaps lower than the industry benchmark for that period.

Printing was a labour intensive process in the 1940s though a lot of the printing machines were now powered by electricity. Besides the employees on their roll, Vakils also employed daily wagers and casual staff. ‘Employee expenses’ was the largest head of expenses and were as much as 50 % of sales revenue. One of the aspects of the national movement

against the British colonial government was an increased political activism among the labouring classes. Political parties encouraged workers to band together in unions to collectively negotiate with management. The Vakils Press Workers Union was in existence all through the thirties until it merged into the Bombay Press Workers Union in 1939. The persistent demands of the union for higher salaries and bonus placed considerable pressure on a mid-sized organisation like Vakils. After Indian independence in 1947, union activity was synonymous with political pressure and the annual reports constantly refer to them. For instance, the annual report for 1953–54 addressed to the shareholders of Vakils paints a dark picture.

Your Directors have to draw attention that due to the Labour Award of the Industrial Tribunal and another award of the Labour Appellate Tribunal, the wages and salaries show an increase of Rs 53,798/- while the corresponding increase in the turnover amounts to Rs 18,207/-. The hours of work had also to be reduced and the number of days of leave and holidays had to be increased. The additional burden of rising wage scales and ever increasing demands by the Labour Union do not promise a very bright future.

Two years later, in 1955–56, the situation was grimmer: “The relations with the labour deteriorated to a very great extent, and a number of cases were referred to the Labour Department. Due to outside influence, the workers resorted to an illegal strike. Your Directors are glad to inform you that the outside influence of political parties is gradually waning.” Notwithstanding this optimism, labour relations remained an important aspect of business management in printing companies like Vakils.

The Mehtas soon realised that unless the machines and technology were regularly upgraded, they would not be able to run the business profitably which is evident from a note in the annual report for 1953–54.

Your Directors regret to bring to your notice that the condition of the old machines is deteriorating and the rate of production is falling low and it is becoming absolutely imperative to scrap or replace most of the old machines. Your Directors feel that very drastic changes in the present machineries is necessary. More labour saving devices and speedier machines have become very essential in view of the excessive labour charges and keen competition.

Investments in plant and machinery began in right earnest from 1953 and continued for the next few years. A second shift was introduced in 1954 to augment the printing capacity and ensure that the machines were optimally used. Over a period of five years from 1952–53, Vakils spent Rs475,000 on new machinery. These investments were funded entirely by unsecured loans from the directors and other shareholders and their families. Debt funding, which was zero in 1948, had risen to Rs 431,000 by 1956–57. While they relied largely on unsecured funding, Vakils also took loans from Morvi Mercantile Bank Limited which were secured against their paper inventory. It was important for a printing business to stock large amounts of paper, an artificially scarce commodity, since the Indian government issued very limited licenses for its importation.

As business volumes grew, higher levels of working capital investments were also necessary. Cash sales were negligible and the average credit period for customers was three months. Inventories, especially paper, grew disproportionately to sales. On the other hand, the Mehtas were alacritous in paying their suppliers. This meant that the cash conversion cycle hovered around 200 days.

Business expansion also required more space. When they got a chance in 1953–54 to acquire the business of their next door neighbours, Trinity Stores & Supply Co owned by Neville Mistry, the Mehtas did not let the opportunity slip by. They could thus get valuable space for housing their fast growing business. But this was not enough. By 1956–57, the directors felt that “the difficulties created by lack of space will halt the progress of the Company. It is imperative that the Company should have its own factory building, which, of course, will require additional finances.”

A Bright Future

After three years in the printing trade, the Mehta family and its chief representative in Vakils, Gunvantrai U Mehta, acquired the confidence to make substantial investments in the business. By 1956–57, they had practically replaced the entire printing machinery and fully modernised its operations. Except for a Victoria Platen Press and three Chandler & Price treadle machines, none of the old machinery seems to have survived. Not only did they put their own money into it, the Mehtas also induced their clansmen to invest in the equity and debt of Vakils. As they wound up their presence in South Africa, more family members joined the business as employees. Not only did they invest resources in acquiring specific expertise in printing, they also trained the second generation of the family to become professional printers by acquiring formal qualifications abroad. Their focus on colour printing seems to have paid rich dividends. They were able to produce art books of the highest quality which won them awards for excellence in printing from the mid-fifties.

The strong foundation laid by the Mehtas ensured the survival of Vakils seventy-five years after their first association with it. The company could navigate successive technological upheavals and reinvent itself multiple times in this long period.

.jpg)

I am very grateful to Bimal Mehta for providing access to the Vakils archive and for sharing his deep insights in the history of the printing business

.JPG)

See All

See All