Print History: Nababharat Press - A Cuttack Print House

Not many Indians involved with printing have written autobiographies detailing their experience in the world of print. Three autobiographies linked to the Nababharat Press provide an inside perspective into the world of Odia printing in the 1930s

30 Sep 2022 | By Murali Ranganathan

The nineteen hundred and thirties were an exciting decade for Cuttack. The city had emerged as the nerve centre of a region which was reinventing itself after two hundred years of political and economic turmoil. During this period, the identity of the region had been compromised to such an extent that even the Odia language, whose modern avatar can be dated to as far back as the twelfth century, was considered to be at risk of oblivion. Odia-speaking territories were spread across four political entities—the presidencies of Bengal and Madras, the Central Provinces and the combined state of Bihar & Orissa—and were administered according to the imperatives of these provinces. Even as the national independence movement intensified across India, this region witnessed increased political mobilisation and a multifarious efflorescence of Odia consciousness. The interweaving of these strands culminated in the formation of the state of Orissa (now Odisha) in 1936, the first state of India to be based on the principle of linguistic unity.

One of the strands of this cultural and political awakening was an increased activity in the arena of literature and printing. This revolution in print was exemplified by a book project which spanned the entire decade. Gopal Chandra Praharaj (1874–1945), an advocate by profession, had made it his life mission to endow the Odia language with a dictionary that it could be proud of. Mobilising finances and subscriptions, sometimes reluctantly, from the colonial government and a cross-section of Odia royalty and intelligentsia, Praharaj marshalled the services of an army of volunteers and paid assistants to bring his dream project to a denouement. It was initially projected as a two-volume dictionary to be sold for thirty rupees to subscribers. However, the Purnnachandra Ordia Bhashakosha (A lexicon of the Oriya language) burgeoned to nearly ten thousand pages over seven volumes published between 1931 and 1940 and was eventually priced at one hundred and fifty rupees. The dictionary captured the imagination of the Odia nation.

Even as the effects of the global economic depression were felt across India, newspapers and magazines were being started in Orissa. Textbooks were being written anew; books were being written in new genres; translations from other languages gathered momentum; and inevitably, printing presses were being founded to cater to the increased demand. One such press was the Nababharat Press.

Founding of Nababharat Press

The personality of Nilakantha Das (1884–1967) loomed large in Odia public life for many decades in the twentieth century. As a public intellectual of the first order, Nilakantha Das had, by 1933, achieved recognition as an educator, writer and politician in the Odia-speaking areas.

He was a member of the Central Legislative Assembly during 1924–30 and played an important role in creating an environment for the formation of the state of Orissa. Though he had been contemplating starting a monthly magazine for years, the circumstances seemed propitious in 1933. In his autobiography Atmajibani (An Autobiography, 1963), Das recalls the period when the magazine and the associated press were founded:

Nilakantha Das (1884–1967) in the 1930s

In 1933, I visited Kolkata from Delhi. Chintamani Misra, who had been my student at Satyabadi School, was in Kolkata and came to meet me. … During that meeting, it was decided that I would bring out a monthly and [he would assist me]; for that reason he would come and stay at Cuttack. This monthly was to be named Nababharat. Before he became the king of Jeypore, Maharaja Vikram Deo Verma had proposed that I bring out a monthly [which he would fund]. Therefore, I went to meet him now. He promised me a sum of five thousand rupees and immediately gave me three thousand rupees. I signed on a receipt which mentioned that I had received five thousand rupees from the king and borrowed another two thousand rupees so as to start Nababharat.

Unlike other contemporary Odia magazines which were largely interested on literary and cultural subjects,Das envisioned that Nababharat would focus upon political questions and economic issues. As its name suggested, the new magazine would have a pan-Indian vision unlike its predecessors that seemed to have restricted themselves to Utkal. While Nilakantha Das was the designated editor of Nababharat, Chintamani Misra managed the day-to-day activities of the Nababharat Press. Misra (1904–1980) was an author who had published two novels before 1933. In the first volume of his autobiography Ardha Shatabdira Anubhuti (Reminiscences of Half a Century, 1983), Misra recalls how the infrastructure for the Nababharat Press was acquired for three thousand rupees:

Cover page of autobiography of Chintamani Misra (1904–1980), Ardha Shatabdira Anubhuti (Cuttack: Nabajivan Pustakalaya, 1983)

[In Dhenkanal], I found a double crown flatbed, a foolscap folio treadle and a cutting machine. All these were very old but were manufactured by reputed English companies. There were many kinds of Odia and English types but I found only five or six cases containing types which could be used for printing. All these machinery made me feel extremely happy. Even in those days, when things were rather inexpensive, all these would have cost at least ten thousand rupees.

Thus, the Nababharat Press, came into existence in early 1934. The first issue of the eponymous magazine appeared in June 1934. The infrastructure of the press and its workings were outlined by an employee who joined the staff later that year.

Nilakantha Das had rented a building from advocate Sushil Chandra Palit to house the Nababharat Press. It was in Bankabazar Lane which branches off the road leading to the Binod Bihari temple. The building at the front was separated from a thatched-roof structure towards the rear by a cemented courtyard which contained a tulsi brindaban and a well. The empty sandy space behind the house was overgrown with shrubs and fenced with thorny hedgerow. The front building comprised three rooms, two on the ground floor and one on the upper floor. One of the ground floor rooms served as the office where Chintamani Misra, the manager of the printing press, worked. He was assisted by a clerk named Mukund Misra and a docile and dutiful young man called Indramani who did the odd jobs. Indramani dispatched copies of the monthly Nababharat to subscribers outside Cuttack, delivered copies to subscribers within the city, took proofs to the publisher and brought back the corrected sheets, and purchased consumables necessary for running the press.

The other room on the ground floor served as the machine room and housed an old flatbed press. When the Dhenkanal Jail Press procured a new flatbed printing machine, its old flatbed machine was auctioned off. Nilakantha Das persuaded the king of Dhenkanal to sell it to him at a very low price. Once the machine was reconditioned, it worked wonderfully well. Apart from this, a new treadle machine had been installed on the veranda of the machine room and this was used to print book covers, pictures, handbills, etc. Like everywhere else in Odisha, there was no electricity in Cuttack in those days. … The flatbed machine could be operated by physically rotating two very large and heavy flywheels placed on either side. Strong labourers had to be hired to perform this task. As the treadle machine was operated by a foot pedal, the printer was free to use his hands to operate the press.

The structure at the rear comprised four rooms.

The two bigger rooms housed the compositors and binders. A third room served as the inking room where the rollers were inked. The fourth served as a kitchen.

The employee who wrote this graphic account of the printing press was Krushna Chandra Kar (1906–1995). Then a young man in his twenties, Kar, who was an aspiring Odia writer, already had considerable experience in the publishing and printing world. After graduating from a teacher’s training school, Kar joined Cuttack Trading Company, a prominent publisher of Odia books. He had also helped a cousin establish and run the Saraswat Press. He describes the circumstances in which he was recruited by the Nababharat Press in his autobiography, Hajila Dinara Smriti (Memories of a Lost Time, 1991), written over half a century later:

Krushna Chandra Kar (1906–1995) in 1935

After the Nababharat Press was established, the manager Chintamani Misra, for reasons of economy, took upon himself the task of correcting the proofs although he bore the heavy burden of overseeing the printing business. He was a highly learned man but many errors escaped his attention. Sometimes, the proofs corrected by him differed substantially from the original manuscript and created extremely awkward situations. The authors were deeply upset but did not dare voice their protest for they were scared of Nilakantha Das, the proprietor of the press, who was notorious for his irascibility. However, when the numerous printing errors in the textbooks reprinted by the Nababharat Press created an embarrassing situation, Chintamani Misra realised the seriousness of the problem.

Cover page of autobiography of Krushna Chandra Kar, Hajila Dinara Smriti (Cuttack: Granthamandir, 1991)

The first issue of Nababharat drew a hostile response from the editor of Utkal Sahitya, Bishwanath Kar, who remarked that “its articles exude arrogance and are riddled with typographical errors.” The Cuttack Trading Company was the main client of the Nababharat Press in its early days. Its proprietor, Akuli Misra, also issued an ultimatum that unless the Nababharat Press hired a good proofreader, they would take their custom elsewhere. The manager, Chintamani Misra, succeeded in convincing Krushna Chandra Kar to join the new press. Kar recalls his first day at this new job in his autobiography:

On 1 Nov 1934, I joined Nababharat Press at 8:30 a.m. … I found uncorrected proofs on my table, and soon, more of these arrived. However, the amount of work that needed to be done was not at all demanding. More than half the proofs lying on my table were galley proofs; the rest included two final proofs and one machine proof. I corrected the proofs with effortless ease before midday and sent them to corrector concerned. When I returned in the afternoon, I found some more uncorrected proofs placed on my table and others kept arriving. With Kulamani’s help, I began separating the chaff from the grain. The compositors and correctors in Cuttack admired me because they thought I found more chaff in the proofs than grain. The errors I spotted while going through the galley proofs enabled the correctors to prepare error-free page proofs. This made the task of the correctors easier and they received their wages without doing much work.

The period of turmoil which the Nababharat Press went through during the first year of its existence must have been typical for that period. Krushna Chandra Kar did not stay for long at the Nababharat Press. There were many opportunities for a careful proofreader in Cuttack and Kar joined the Bhashakosha Ashram in 1935 when the fifth volume of the Purnnachandra Ordia Bhashakosha was being compiled. Chintamani Misra, who was the mainstay of the press, had a longer tenure during which Nababharat appeared regularly. However, by 1941, the tensions between him and Nilakantha Das came to a boil and he resigned. After their departure from Nababharat Press, Misra and Kar continued to be associated with the printing industry and had long and successful literary careers.

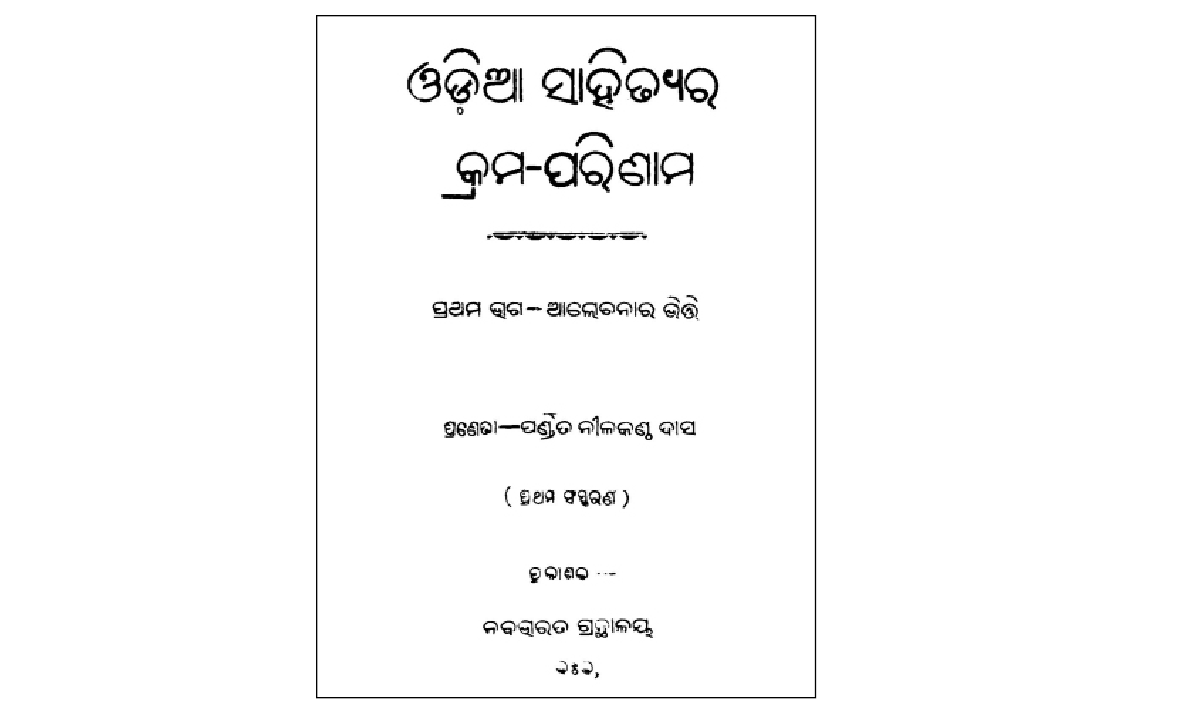

Book printed at Nababharat Press: Nilakantha Das, Odia Sahityara Krama-parinama [The Genealogy of Odia Literature] (1948)

The monthly magazine Nababharat ceased publication in 1941 and was replaced by a newspaper of the same name during the Second World War. The management of the press was taken over by Nilakantha’s son, Ashok Das. Nilakantha Das aspired to play a greater political role and perhaps could not devote the time for printing and publishing activities. The press continued to undertake job printing assignments which were its main source of revenue. The magazine was revived in 1946 and seems to have been in existence until 1953 when poor health prevented Nilakantha Das from paying attention to its affairs. The printing infrastructure of Nababharat Press was taken over by the Loksevak Mandal. However, Nababharat Press remains alive in the detailed narratives of the three autobiographies of its proprietor, manager and proofreader.

The author is grateful to Jatindra Kumar Nayak and Animesh Mohapatra for identifying the autobiographies and translating the quotations from Odia to English. Image credits: www.odiabibhaba.in

See All

See All