Print History: Gujarati Type Foundry - Print Patriots

A print organisation deeply enmeshed in the freedom movement aspires to manufacture world-class high-quality products

29 Feb 2024 | By Murali Ranganathan

On the second of February, 1943, a posse of policemen headed by Deputy Inspector Rane raided the premises of the Gujarati Type Foundry at Girgaum, a buzzing business and residential neighbourhood in the heart of Bombay. Based on a tip that explosives were being manufactured in the type foundry, the police claimed to have first discovered a wooden box which contained “15 iron casings and 7 half casings.” A further search unearthed another “wooden box, which, when opened, was found to contain an aluminum conical-shaped live bomb, rolled up in a piece of paper.” The prime suspect was Surendra Manilal Modi, the Works Manager of the Gujarati Type Foundry. Charged under the Explosive Substances Act, Surendra Modi was arrested to await trial at the Sessions Court of Justice Rajadhyaksha.

This charge was the culmination of over three decades of nationalist sympathies espoused by the Modi family, the proprietors of the Gujarati Type Foundry. Founded in 1900, the Gujarati Type Foundry gradually built up a reputation as manufacturers of high quality types in a range of scripts. And this reputation was cemented by the type catalogues which it issued at regular intervals. The Gujarati Type Foundry catalogue was first issued in 1902 and widely distributed to printers in India and abroad. And as the range of their typographical offerings expanded, their catalogues grew to be more voluminous and impressive. In the 1930s, a decade of fervent nationalist and economic activity, the catalogue of the Gujarati Type Foundry reached its apogee. However, its beginnings were rather humble.

The Early Years

The Gujarati Type Foundry was founded in October 1900 by Ichharam Suryaram Desai and Maganlal Thakordas Modi. Desai was also the editor and proprietor of the Bombay weekly newspaper, Gujarati after which the type foundry was named. Started in 1880, Gujarati was one of the leading newspapers of that period in Bombay and played a prominent part in popularising the activities of the Indian National Congress. At a time when type had to be largely imported from Europe, a local type foundry which could match the quality and style of international type founders was very much the need of the hour. The early years of the foundry are outlined in its Marathi and Gujarati catalogues, first compiled in the mid-1920s.

About twenty-eight years ago, we were advised by our well-wishers to establish, on a commercial scale, a workshop to manufacture types. However, we were unable to act on their sage advice at that time. In June 1901, the moulds (matrices) required to cast types were being manufactured in a thirty-square-feet room in Gaiwadi, adjacent to the Panjrapole in Girgaum. Within three months, the space proved inadequate and we moved a short distance to a rented room of about 150 square feet. It took us four months to fabricate two machines needed to manufacture type. Finally, from January 1902, we began to cast type and sell it. Our first customer was the printing press of the newspaper, Gujarati. Gradually, the demand for our types increased and we even had to refuse a few orders [because we could not fulfil them]. The circumstances were encouraging enough for us to increase our manufacturing capacity and by the end of 1902, six type casting machines were in operation.

The Gujarati Type Foundry claimed to be the first Indian type foundry to manufacture what it termed “superior copper alloy types.” The alloy used to manufacture the types contained 1% copper; the addition of copper hardened the type and contributed to its longevity. Though they were more expensive than ordinary types, they worked out cheaper for the printer in the long run. Another innovation which the Gujarati Type Foundry claimed to have pioneered in the Indian context was the adoption of the America pica system, formalised in 1888, to standardise font sizes. Termed “print-line-set systems” by the foundry, they were first introduced in 1903. The Gujarati Type Foundry “introduced Italic types, slanting uniformly to the right, in both Devanagari and Gujarati; adopted uniform system in set size, and height; and cast types in the Akhand system so as to reduce the use of ¼ body letter-degrees to the minimum.” Though they started by duplicating typefaces of the Jawaji Dadaji Type Foundry, they also “cut several new type faces in Marathi, Gujarati, Urdu, Sindhi, Kannada and Gurumukhi.” (Bapurao Naik, Typography of Devanagari, vol 1.) Most of their roman typefaces were also copies of standard European and American designs.

Besides selling to Indian printers, the Gujarati Type Foundry was, perhaps, the first Indian type manufacturer to target the American market. A type specimen book was sent out to printers and printing trade magazines in the United States of America in 1914. Whether it acquired any American customers is not known, but its catalogue got numerous glowing reviews, like this one in The Inland Printer (July 1916).

That native Indian printers are capable, under proper conditions, of producing extraordinarily good work, is proved conclusively by the beautiful book of specimens sent out by the Gujarati Type Foundry, of Bombay, a concern run entirely by Indian capital and Indian labor. This house produces a great deal of really excellent work, both in roman type and in the script of various native languages. It has recently sent us its specimen book with insertions bringing it up to date and although some of the display-work is what American printers would consider old-fashioned, it is doubtless suited to the requirements it has to meet, and the general workmanship is of the highest class.

Around the same time, the Gujarati Type Foundry introduced another product line: blocks of illustrations. Some of these images were based on Hindu mythology while others were inspired by nature. These blocks were manufactured by electrolysis using wood engravings and were called “electro-blocks.” A catalogue of blocks was separately issued in which the Gujarati Type Foundry averred that, “As we were the first and foremost ten years back to cast types on print-line-set systems, so we are again ahead in this new enterprise, which is so much valued by the Indian printer and the public at large.”

Ichharam Suryaram Desai, who had exited the business, died in 1912, thus severing any formal connection of the Gujarati Type Foundry with Gujarati and its printing press. The Gujarati Type Foundry was now owned by the Modi brothers, Maganlal (1852–1926) and Chhaganlal (1857–1946). Natives of Surat, they were the sons of Thakordas Balmukundas, a prosperous cotton merchant from the Dishaval Bania community. They were educated in colonial institutions; Maganlal qualified as a civil engineer from the College of Engineering in Pune while Chhaganlal acquired a BA degree from the University of Bombay. Both of them were first employed by the Baroda State. However, Maganlal soon became a trader, perhaps inheriting his father’s business. Partnering with some of the leading cotton merchants of the day, Maganlal entered the upper echelons of Bombay business. Chhaganlal, on the other hand, had a long career in Baroda as a teacher and retired as its chief educational officer. He also authored a few books for the use of schools. It was only after his retirement in 1915 that he became involved with the operations of the Gujarati Type Foundry, though he continued to stay in Surat. After Maganlal’s death in 1926, Chhaganlal Modi became the sole proprietor of the Gujarati Type Foundry.

The first person from the Modi family who acquired technical expertise in the operations of the type foundry was Manilal (1883–c.1950), the elder son of Chhaganlal Modi. After completing his studies in the visual arts at Kala Bhavan in Baroda, Manilal joined the Gujarati Type Foundry in 1906 and soon rose to become its Works Manager. As Bapurao Naik notes in Typography of Devanagari, the following years were very busy for the Gujarati Type Foundry.

Blocks based on Hindu mythology, from a 1913 catalogue

By 1908, the Gujarati Type Foundry introduced Italic type in 48 point and 36 point Marathi, and 48, 36, 28, 24 point Gujarati. By 1914, Akhand body Marathi types up to 22 point with left and right angular velantis, Italic types in 16 point body in Marathi and two new faces known as 12 point and 18 point New Style Gujarati, were put in the market. During the year 1917/18, the Gujarati Type Foundry introduced shaded types.

As the business grew, more hands were needed to manage it. Manilal’s younger brother, Dhirajlal (1893–1980), had graduated with a BA degree in 1914 and joined the cotton trade, perhaps with his uncle, Maganlal. In 1926, he also joined the Gujarati Type Foundry as its Business Manager. Manilal’s son, Surendra entered the business soon after.

Acquiring a Public Spirit

Even as they successfully managed the Gujarati Type Foundry, the Modi family also played a prominent role in the public sphere. The patriarch, Thakordas Balmukundas, was a famed philanthropist and headed the Hindu Charities Fund in Surat for two decades. Chhaganlal Modi was one of the founders of the Surat Mahila Vidyalaya for the education of girls. In 1920, he persuaded his brother, Maganlal, to donate two lakhs of rupees to the institution to upgrade it to a college, which was later named the Maganlal Thakordas Balmukundas College.

The Modi family was at the forefront of formally organizing the printing and publishing industry in Bombay. In 1915, they helped found the Press Association of India to combat the strictures of the Press Act of 1910. Manilal Modi was secretary to the delegation led by Madanmohan Malviya which met the viceroy of India to protest the Act. He continued to agitate against the Act until it was repealed in 1922. Manilal Modi also took the lead in founding the Bombay Press Owners’ Association (in 1919) and Bombay Type Foundry Owners’ Association (in 1923). All these organisations were housed in the premises of the Gujarati Type Foundry at Girgaum and Manilal served as their honorary secretary for many decades.

There were no institutions in Bombay where students could acquire the skills necessary to join the printing trade. Since all employees had to be trained from scratch, printing companies struggled to find qualified candidates. To alleviate this situation, the Modis established the Academy of Printing in the 1930s which taught printing trades and certified candidates after examining them. Four trades were offered: composing, proofreading, bookbinding and machine minding. They also arranged for the screening of films connected with advancements in the printing industry at the Cinema Majestic, located conveniently next door to their premises in Girgaum. The premises at Gaiwadi was the venue for many meetings, especially during the Bombay tours of printers, publishers and newspaper editors with nationalist proclivities such as Tushar Kanti Ghosh, editor of Amrit Bazar Patrika. These activities dovetailed with their strong patriotic sentiments which manifested itself strongly in the 1930s.

After a lull in protest activities in the late 1920s, a recharged Congress, under the leadership of M K Gandhi, tried to derail the British colonial government by launching the Civil Disobedience Movement in early 1930. Even as Gandhi began walking on twelfth of March, 1930 to the seashore at Dandi to break the salt laws, Bombay was convulsed with protests. As card-carrying Congressmen, the Modi family was deeply involved in organising and supporting these protests.

One of the first repressive measures introduced by the government was the Press Ordinance of 1930 (later the Press Emergency Act, 1931). The printing fraternity in Bombay was at the forefront of protests against the Ordinance. They protested its promulgation “as an affront to independent journalism, as opposed to all canons of civilised Government, and calculated to give a death blow to the printing trade specially and allied trades and industries generally, thus involving the unemployment of thousands of skilled and unskilled workers.” (Bombay Chronicle, 5 May 1930.) As Secretary of the Press Owners’ Association, Manilal Modi was very involved in formulating a strategy to combat the Ordinance. He was one of the secretaries of the Executive Committee set up to mobilise the press all across India while Dhirajlal Modi was named a treasurer.

The police were quick to suppress the protests in Bombay and swiftly arrested the leaders of the Congress. Each arrested leader would nominate a replacement to ensure that the protests continued unhindered. When Perinben Captain was arrested, she nominated Dhirajlal Modi to replace her as the president of the Bombay Provincial Congress Committee. Soon after, on 4 July 1930, he chaired a meeting in which 10,000 persons were present. This led to his arrest and imprisonment. A few months later, in October 1930, his nephew, Surendra Modi was also arrested. As captain of the Congress Ambulance Brigade, Surendra was responsible for providing timely medical aid to satyagrahis who were injured in the frequent lathi charges made by the Bombay police. Though the policy of the Congress was not to contest any arrest, an exception was made for Surendra Modi and his colleagues because of the critical nature of their work. A stout legal defence was mounted which resulted in his acquittal. However, he was again arrested in January 1931 as he tried to calm down a rambunctious crowd of protestors.

This cycle of arrests and imprisonment of its key managers would have affected the business of the Gujarati Type Foundry. It, however, seems to have weathered this storm and when nationalist protests tapered off in 1932, the Gujarati Type Foundry was ready to do business again.

A Type Specimen Catalogue for the Nation

When a group of printers and newspapers editors including A Ramaswamy Iyengar of Swadesh Mitram (Madras) and N C Kelkar of Kesari (Poona) visited the Gujarati Type Foundry on 4 June 1927, they were glad to note that Manilal Modi “paid greater attention to the art and development of typography rather than to mere profit from the institution.” Working closely with his type designers, Manilal significantly widened the offerings of the Gujarati Type Foundry between 1932 and 1937. And in the latter year, a new type specimen book was issued by the Gujarati Type Foundry which has come to be recognised as a publishing landmark in the history of Indian type. The message which it sought to convey through the catalogue was that, “Any visitor to the Gujarati Type Foundry will acknowledge that we are the equal of any European or American type foundry.”

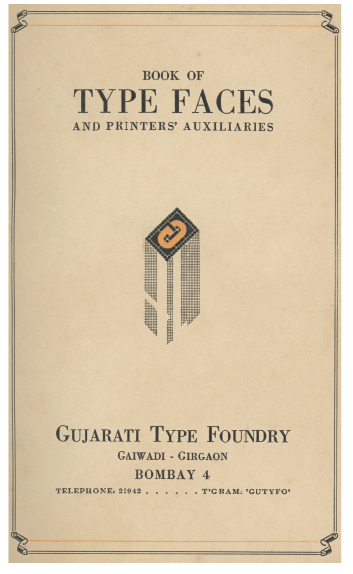

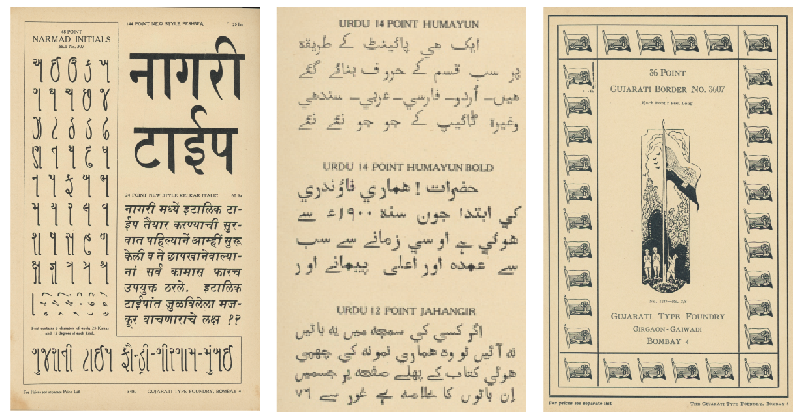

Titled Book of Type Faces and Printers' Auxiliaries, the type specimen catalogue extended to over 400 pages. It featured the entire range of offerings of the Gujarati Type Foundry including all its typefaces and auxiliaries such as rules, borders and ornaments. Each typeface was illustrated in all the available styles and font sizes. Given the nationalist fervour of the time, many of the roman typefaces were assigned names connected with political figures. George Osbourne (‘An Unusual Type Specimen Book from India.’ Matrix 1982) has identified some of the original names: “Clarendon becomes Tilak, Sudama is Cheltenham Bold Shaded, and a Civilite is offered as Pherozscha Script.” The Devanagari typefaces have names associated with the Maratha period: a 144-point and a 96-point for use in posters are respectively named Peshwa and Manaji while a 24-point ornamental typeface is named Tanaji. The Urdu typefaces are named after Mughal emperors: Babur (18-point), Humayun (14-point), Jahangir (12-point) and Shahjahan (10-point). A few typefaces are named after their designers; for example, 22-point Anant Shaded after Anant Chari and 24-point Vasant Marathi after Vasantrao Oturkar. Each page also had borders from the ornaments series, with names invoking Indian personalities: Nehru Niceties, Jawahar Decorators, Scindia Border, Sayaji Series, etc.

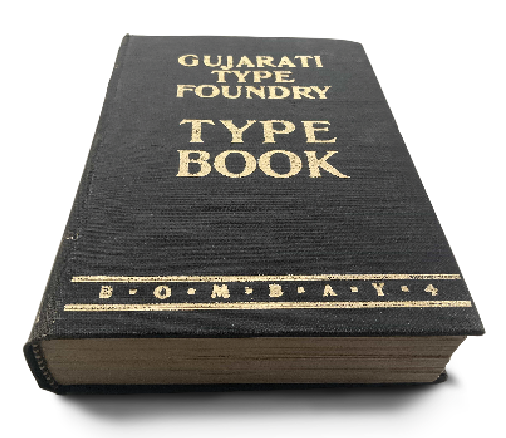

From the very start, the Gujarati Type Foundry had designed its type specimen catalogues to be informative and useful to Indian printers. Instead of illustrating its typefaces with irrelevant text, it chose to include material related to the printing arts. It would serve as a printer’s manual in a country where such material was scarce, especially in non-English languages. For example, a catalogue in the Gujarati language traces the history of the type foundry in Bombay to 1812 when Furdoonjee Murzban cast types in Gujarati. After giving a brief history of the firm (quoted earlier), it then goes on to explain the usefulness of the point system and how types from various foundries or of different scripts can be used together. Since the pages were not numbered, they could be bound up in various formats depending on the profile of the intended recipient. Thus, the catalogue exists in numerous versions, but all of them have a hardbound cover (in a variety of colours) with gold lettering.

While inaugurating the first Devanagari Monotype installation at Pune in 1932, Manilal Modi assured traditional typefounders that the advent of hot metal composing would not endanger their trade: “with rising literacy and given India’s economic circumstances all forms of printing and typefounding practices would need to coexist.” And Modi’s prediction proved right for nearly fifty years. (Vaibhav Singh, ‘The first Indian-script typeface on the Monotype.’ Journal of the Printing Historical Society, 2018).

Epilogue

By the 1940s, Manilal Modi had handed over the management to his son, Surendra, who was now the Works Manager. Presumably, his nationalist ardour had not cooled in 1942 when the Quit India Movement was announced at the height of the Second World War. Many Congressmen, who had earlier espoused non-violence and satyagraha, were now willing to explore other means of protest. Perhaps Surendra Modi was one of them. He must have been on the police radar because of his earlier arrests and a few coded telegrams further raised suspicions. And he was arrested on charges trumped up by an overworked police department.

Surendra Modi’s trial for possessing explosives continued all through 1943. In July, his accomplice was discharged but Surendra was formally charged. The police could, however, not mount a serious case; perhaps, the evidence had been planted. Eventually, he was acquitted of all charges in December 1943 by the Sessions Court. However, instead of being released, Surendra was again arrested under the Defence of India Rules and sent to the Nasik Central Jail. He was eventually released in May 1944. After 1947, like many other activists without political aspirations, Surendra Manilal Modi went back to being a typefounder. The catalogue, however, proved to be a timeless production that the Gujarati Type Foundry continued to distribute as late as the 1990s.

I am grateful to Vaibhav Singh, print historian and editor of Contextual Alternate, for the images from the Gujarati Type Foundry type specimen book used in this article.gujar

See All

See All