Boom in K-12 enrollment fuels India’s book printing industry

The K-12 education sector is a dominant force. In 2024, NCERT announced a plan to print 15-crore books, nearly three times its previous production. Words: PrintWeek and Bindwel Research Division

08 May 2025 | By PrintWeek Team

With 248 million students enrolled in 2023-24, the demand for textbooks and educational material remains robust. The National Education Policy (NEP) 2020 is expected to accelerate the need for high-quality printed books, making it imperative for the book printing industry to scale up production, improve quality, and innovate distribution models.

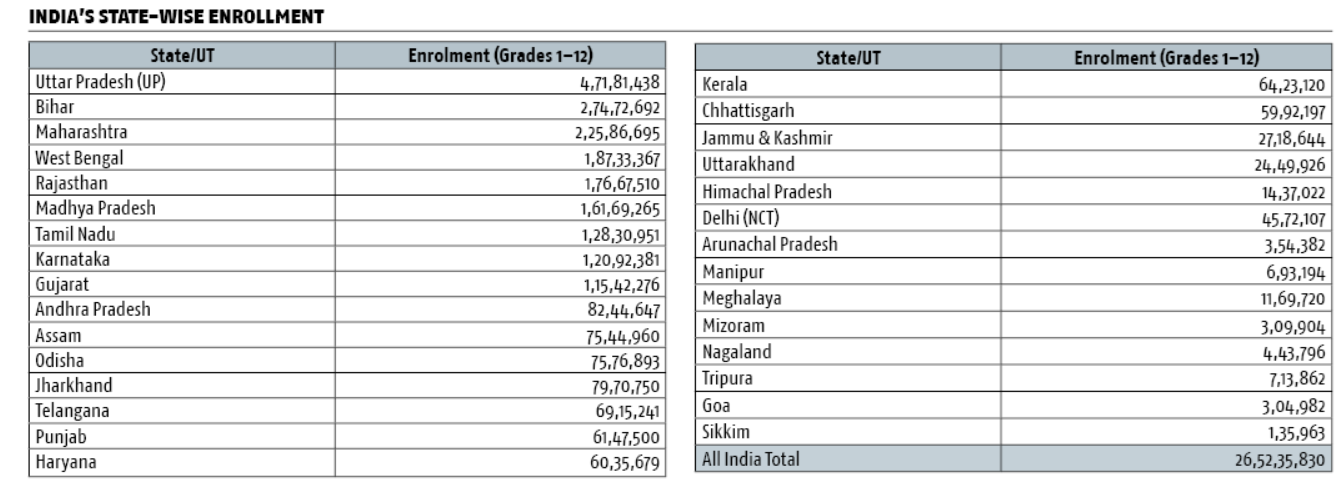

Enrollment data (Overall levels)

India has one of the largest K‑12 education systems in the world. According to the latest Unified District Information System for Education Plus (UDISE+) data, the total number of students enrolled from grade one to 12 across India is about 24.8-crore (248-million) in the 2023–24 academic year. This marks a slight decline from 25.18-crore in 2022–23, a trend attributed in part to improved data accuracy (eliminating duplicate counts) and demographic changes.

Of the total enrollment in 2023–24, boys account for around 12.87-crore and girls around 11.93-crore, roughly a 52:48 ratio. Over the past few years, the overall K‑12 enrollment hovered around 25-26-crore, peaking at around 26.45-crore in 2019–20 before the recent drop. Encouragingly, gender parity has improved greatly over time, with girls now nearly half of all enrollments.

The enrollment numbers had been relatively stable pre-pandemic, but UDISE+ 2023–24 data revealed a net drop of about 1.2-crore students (~6%) compared to 2018–19. Education officials note that this decline may reflect more accurate tracking of individual students (via Aadhaar-linked IDs introduced in UDISE+) rather than a mass exodus.

In terms of grade levels, recent data indicate enrollment increases in pre-primary and higher secondary grades, but notable declines in the primary, upper-primary, and secondary grades – possibly due to smaller incoming cohorts and dropout issues at the middle and secondary level. The gross enrolment ratio (GER) at the elementary level is high, but it drops at secondary and higher secondary levels, highlighting the need to retain students through secondary school. State/UT Enrolment (Grades 1–12)

A surge in textbook demand

India’s textbook publishing ecosystem is vast, with NCERT at the helm, producing textbooks for CBSE schools, and state governments handling regional publications. In 2024, NCERT announced an ambitious plan to print 15-crore books, nearly three times its previous production, reflecting an increased push towards curriculum standardisation and improved learning resources.

India’s textbook printing runs are staggering, reflecting the large student population. The top 10 states by textbook volume roughly correspond to the states with highest enrollments. These include Uttar Pradesh, Bihar, Maharashtra, West Bengal, Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, Gujarat, and Andhra Pradesh. In these states, annual textbook production easily runs into multiple crores of copies per state.

To illustrate, Uttar Pradesh in 2023 aimed to print and distribute about 16-crore textbooks for classes one to eight. This was for free distribution in government schools; additional copies would be printed for higher classes and private schools. Maharashtra, in 2022, printed about eight to nine-crore textbooks in total for the year (over 5.4-crore for free distribution to public primary schools and around three-crore for sale in the open market up to class 12). Bihar and West Bengal, each with over two-crore students, likely produce in the order of nine to twelve-crore textbooks each yearly, considering many of these students receive books in multiple subjects. Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Tamil Nadu, Karnataka, and Gujarat print many crores of textbooks per year.

For example, Tamil Nadu supplies free textbooks up to class 12 for all state-board students, which would entail printing book sets for ~1.2 crore children in two mediums (Tamil and English).

So, comparatively, the central NCERT’s production (even at 15 crore copies for the whole country ) is just one piece of the puzzle – individual large states rival or exceed that in their own textbook demand. The logistics behind this are immense: from content development, paper procurement, printing, to warehousing and distribution down to tens of thousands of schools.

Delays or shortfalls can affect learning (for example, there have been past instances of textbook supply being delayed into the school year, which states are trying to solve via better management systems). On a positive note, the high volume also means economies of scale – government-printed textbooks are generally inexpensive per copy.

In recent years, states have also started embedding QR codes in textbooks (through the national DIKSHA platform) to link to digital content, reflecting a blend of print and digital approaches.

Board-wise enrollment distribution: Dispelling the myth of a mass shift to CBSE

India’s K‑12 students are educated under a variety of school boards and curricula. Contrary to the perception that there is a massive shift from state boards to CBSE, the data tells a different story. State boards continue to overwhelmingly serve the majority of students. According to a recent government study, about 88% of school students are enrolled in state-run boards, whereas only ~12% are in central boards like CBSE or CISCE (ICSE/ISC). This means that nearly nine out of 10 schoolchildren in India continue to study under state education boards.

Each state has its own board for secondary and higher secondary examinations, and these state boards together cover the bulk of both public and private schools in their respective states.

The largest single board by enrollment is actually the Uttar Pradesh state board, which alone accounts for 14–16% of all secondary students in India. Other big state boards include those of Maharashtra, Bihar, West Bengal, Rajasthan, and Tamil Nadu, each covering 6–10% of students.

Among national-level boards, the Central Board of Secondary Education (CBSE) is the largest. As of 2024, CBSE has over 29,000 affiliated schools (including ~240 abroad) and nearly 27-million students, which constitutes roughly 10% of India’s K‑12 enrollment. While CBSE schools, including Kendriya Vidyalayas, Jawahar Navodaya Vidyalayas, private schools, and some state-government-run schools, are expanding, their overall share remains much smaller compared to state boards.

Similarly, the Council for the Indian School Certificate Examinations (CISCE), which conducts the ICSE (Class 10) and ISC (Class 12) exams, has around 2,750 affiliated schools and a much smaller student base, likely accounting for only 1–2% of total enrollment.

Despite CBSE’s steady growth, the overwhelming majority of students in India still study under state syllabi. Most state-government schools and a significant portion of private schools remain affiliated with their respective state education boards. While some schools and students transition from state boards to CBSE, this is not a large-scale migration but rather a targeted shift by select schools and students aiming for standardised curricula and national-level exposure.

The government’s efforts under NEP 2020 are also focused on bringing greater uniformity across all boards, ensuring quality education irrespective of affiliation. The proposed Performance Assessment, Review, and Analysis of Knowledge for Holistic Development (PARAKH) framework aims to standardise assessments and learning outcomes across state and central boards, minimising disparities.

Involvement of private publishers

Alongside government publishing, private publishers play a significant role in K‑12 educational materials. There are thousands of private publishing houses in India producing school textbooks, reference books, workbooks, and guides. Private publishers cater especially to private schools, which often opt for enriched or specialised content beyond what NCERT/state textbooks offer. Many urban private schools require students to buy textbooks published by companies like Macmillan, Pearson, Oxford University

Press, or indigenous publishers – covering subjects such as English language, mathematics, sciences, and even state curriculum subjects with augmented content.

Private textbooks frequently come with glossy prints, updated exercises, and supplementary digital content. However, they come at a cost premium. NCERT textbooks are extremely affordable (often a full set costs only a few hundred rupees), whereas privately published books can be several times more expensive. Despite cost issues, private publishers continue to thrive due to perceived quality differences and variety of offerings. They often provide content in niche areas or advanced levels – for instance, extra preparatory books for competitive exams, more practice problems, or international pedagogy styles. Many state board schools supplement government textbooks with private publishers’ books to give students an edge. Furthermore, private publishers

produce guides, sample papers, and reference books that are widely used by students across all boards for exam preparation.

In recent years, NCERT and governments have taken steps to collaborate with or regulate private publishing. NCERT’s decision to sell textbooks via Amazon and ramp up print runs is partly to undercut the market for pirated or overpriced books. There is also an effort to ensure that any additional books in schools align with the official curriculum (to avoid confusion among students). The ecosystem now is one of co-existence: government textbooks set the core curriculum, and private publications provide additional learning resources. Educational book publishing constitutes about 70% of India’s entire publishing market by value, so both sectors (public and private) are significant.

See All

See All