Print History: The Time Capsule - Plantin-Moretus Museum

How does a printing press make the long journey from being the leading publishing house in the sixteenth century to a world heritage museum in the twenty-first century? In the first part of a series on important printing museums in the world, we explore the history of the Plantin-Moretus Museum

30 Jun 2021 | By Murali Ranganathan

It is high summer in a city located somewhere on the coast of northern Europe. You have been transported to a seventeenth century printing workshop located in the city centre. Rows of wooden presses built to the latest specifications first call your attention. Stacks of paper and rolls of parchment are lined up next to the presses.

Vats of black ink are placed between the presses. The print room is lined with shelves containing types for every script which a scholar in Europe might be familiar with, including Hebrew and Arabic. Finely carved woodblocks are neatly arranged on the walls. There is a bookbinding room next door where stacks of folded folios await binding.

It is early in the morning and the journeymen printers are just streaming in. Each journeyman is responsible for one book and all the folios for that book are printed at the same printing machine.

Proofreaders occupy the tables placed next to the windows to take advantage of the light.

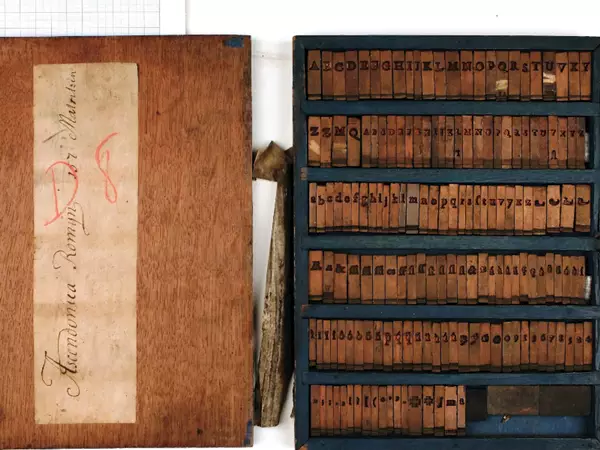

As you venture deeper into the cavernous premises, you reach a foundry where the types required at the printing press are cast. All efforts have been made to acquire matrices and punches from type designers in the major cities of Europe. The copper matrices or moulds for each typeface are securely stored in wooden boxes which are placed in a safe. They are the key to defining the capabilities of the printing press.

The master printer who stays in the premises is already at his desk in a large reception room decorated in the latest Baroque fashion. The master is checking the proofs of the text composed yesterday. It could be a

dictionary in four languages or the Bible in five.

The founder Christophe Plantin, his daughter Martina, and her husband Jan Moretus; portraits by Rubens

Perhaps it is a royal commission for the King of Spain or maybe an underground tract commissioned by the Protestants. The walls are lined with family portraits executed by the foremost painters of the day. At another desk in the same room is a lady, perhaps his daughter, poring over the accounts ledger of the press. In another corner, a scribe is framing replies to letters which have been received from authors who want to publish their writings. Looking out of the large windows which line the far wall, you see an inner courtyard with a carefully manicured garden and a fountain.

The small room next door is a library containing books printed at the press, arranged by size ranging from folio to duodecimo and smaller. Most of them are bound in leather and embellished with gold tooling. If you perused a few books, you would notice that they are in numerous languages – French, German, Flemish, Latin and Greek. Many are richly illustrated.

You are not the only visitor of the day. The most important personages, including queens and kings, are keen to see the workings of this printing press whose fame has spread to all corners of Europe. After having spent a few hours at the press, you step into a brightly lit room which is evidently a museum shop. It is only then that your reverie is broken and you are back into the twenty-first century. You have just emerged from the time capsule of Officina Plantiniana, now known as the Plantin-Moretus Museum at Antwerp in Belgium.

Officina Plantiniana

Founded by Christophe Plantin (1520–1589) in 1555, the Officina Plantiniana was perhaps the largest printing press in Antwerp. Now part of the country of Belgium, Antwerp was then a thriving centre of global trade and was known as ‘the merchants’ emporium’. Not only was Plantin a prolific printer, the quality of his printed books earned him numerous prestigious commissions. He was appointed the royal printer by the King of Spain and later became printer to the University of Leiden.

Through a combination of business acumen and technological skills, Plantin built up the largest book business in 16th-century Europe. He not only sold his own publications but also ran a lucrative book trade, importing books and prints from other publishers.

During his lifetime, the press printed over 2500 imprints, both big and small. A large number of books were related to the Christian religion and the Bible formed an important part of his repetoire. As the technology to print high-quality illustrations gradually developed, Plantin published numerous works on anatomy, botany and geography including landmark maps and atlases.

Matrices from the sixteenth century

It is said that he was so concerned about the quality of his books that he would display the proof prints on the outside wall of the press so that the general public could examine them and point out any errors.

After Plantin’s death in 1589, the business was managed by his son-in-law Jan Moretus (1543–1610) who had been working at the press from the age of fourteen. He continued in the footsteps of Plantin and focused on the quality of his printed books thus continually enhancing the reputation of the press. Jan and his wife Martina laid the foundation for the longevity of the press by stipulating that the Officina Plantiniana had to irrevocably remain a single entity.

The press remained in the hands of the descendants of the Moretus family for nearly three hundred years. By the middle decades of the eighteenth century, the press had begun to stagnate but still survived. No fresh investments had been made for nearly a century and the press was hardly a commercially viable proposition in the the 1860s when it finally ceased printing.

That the family had failed to modernize the press in the nineteenth century proved to be a blessing in disguise. Practically all the machinery and equipment from the 1600s had survived. The business papers and correspondence accumulated over the course of three centuries constituted an archive which was in an excellent state of preservation.

Becoming a museum

When the City of Antwerp acquired the premises which housed the Officiana Plantina in 1876 for 1.2 million francs and turned it into a museum the following year, it could hardly have imagined that the Plantin-Moretus Museum would eventually be designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2005. Perhaps the only museum in the world to be awarded this honour, it recognized the uniqueness of not only the collections but also of the buildings which housed them.

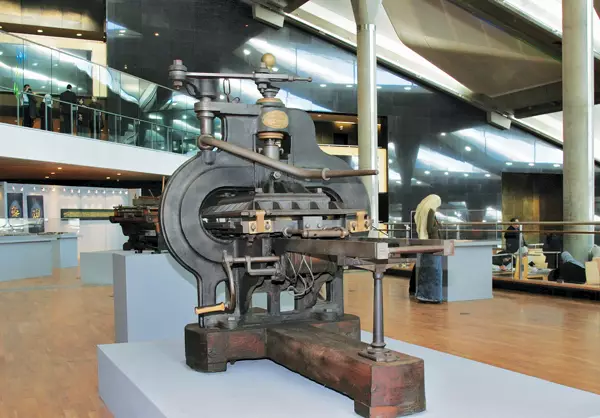

An early printing press, possibly from the sixteenth century

It contains two of the oldest printing presses which have survived for nearly five hundred years besides many others of a slightly younger vintage. The type collection of the museum virtually portrays the history of European typography and contains the original matrices and punches of numerous typefaces which have been recognized as classics.

The activities of the Plantin-Moretus Museum are multifarious. The Plantin Institute of Typography provides short and long term courses in type and book design to professionals and enthusiasts alike. It has a prominent presence in the city of Antwerp and intertwined with the cultural fabric of the city. Nearly a 100,000 guests visit the museum annually and its archives and library are used by scholars researching in a variety of subjects.

Besides a permanent exhibition spread over twenty rooms in the mansion, the museum organizes temporary exhibits to highlight major events such as the five hundredth birth anniversary of its founder in 2020. The Plantin-Moretus Museum has a very strong digital presence with a full-fledged website which can provide a virtual visiting experience. A large part of the archives and prints are also available online.

The Plantin-Moretus Museum employs around forty employees including curators who oversee the various collections and administrators and managers who handle the working of a large public-facing organization.

The press room at the Plantin-Moretus Museum

The Plantin-Moretus Museum and its archives have facilitated research into the world of European printing which has enabled us to obtain a better understanding of the pre-modern world. Of the numerous books on the press, perhaps the definitive history is the two-volume The Golden Compasses: The History of the House of Plantin-Moretus. Published over fifty years ago, it was written by Leon Voet, the museum’s curator for many decades who had devoted his entire life to the development of the museum and archives.

The Musuem has continuously reinvented itself and highlighted different aspects of its rich heritage to remain relevant to its contemporary context. While it would be difficult for most other printing museums to rival the collections of the Plantin-Moretus Museum, they can certainly emulate its modern museological practices so as to contribute to numerous fields associated with printing and culture.

See All

See All