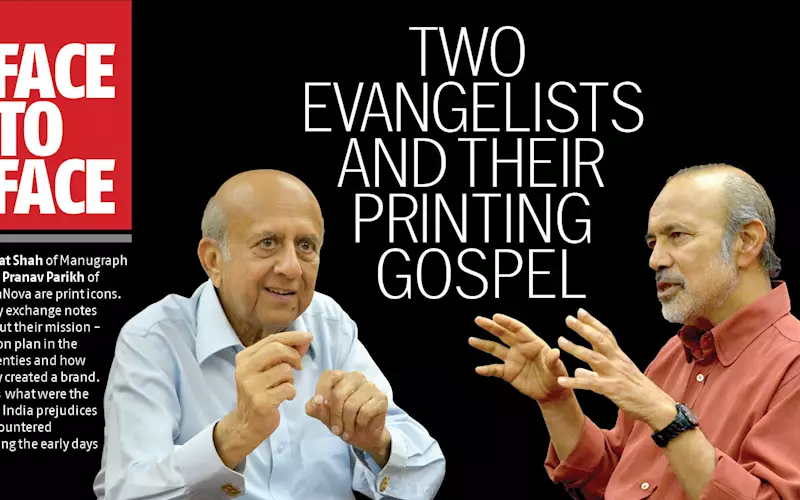

Two evangelists and their printing gospel

Sanat Shah of Manugraph and Pranav Parikh of TechNova are print icons. They exchange notes about their mission-vision plan in the seventies and how they created a brand. Plus what were the anti India prejudices encountered during the early days

19 Mar 2014 | By Ramu Ramanathan

Ramu Ramanathan (RR): We are honoured to have two legends of the Indian print industry here, in Manugraph’s boardroom in Mumbai. Thank you, both of you. Can you define what the Made-in-India brand means to you, and the difficulties in setting up Manugraph?

Sanat Shah (SS): As you know, we began as importers of printing machines but, due to the acute foreign exchange crisis, imports were severely restricted for some years. With large overheads, of salesmen and engineers, I thought about seriously taking up the manufacture of printing machines. In those days, I do not remember whether any precision machinery was made in India. Even Fiat and Ambassador cars were produced for years, made with outdated designs, with no improvement. Only HMT was producing machine tools of average quality.

RR: Was this true about engineering products, as well?

SS: When you talk about engineering products, there was nothing good from the Indian stable, so to say. When I took up the challenge, one thing was sure, that if I produced on my own, the quality should be of international standard. I also knew that I’d have to tie-up with an overseas manufacturer to build quality machines.

After trying hard with manufacturers in Japan, West Germany and USA, I succeeded in my mission with an East German company, and we started, under a collaboration. The East German company laid down the condition that it will give knowhow to manufacture offset presses, provided we start with letterpress first. “What?” I said. Letterpress was being phased out in the world and here was this ridiculous condition.

However, the reason and logic was: you have to learn the art of producing high quality machines. Printing machines are not like textile and machine tools; it has a much higher level of accuracy. It was rightly said by SK Patil, the then chairman of HMT, that, “precision in a printing machine is on par with the aeronautical industry”. So we started with OM-2 as per the agreement, then the web offset RO-62, followed by the blanket-to-blanket eight-page Zircon.

In 1971, when the news spread that I was starting with letterpress, there was shock and surprise, and questions were raised as to why I was doing this. The jury was out that the project would be a failure. Our engineers went through rigorous training on how to produce printing machine parts having high precision; each and every part had a drawing, including assembly drawing. The machines were assembled strictly according to details given in the sub-assembly and main assembly drawings. The first commercial letterpress machine, OM-2, was produced in June 1975, almost three years after laying the foundation stone of the company.

RR: What about TechNova, and your early days?

Pranav Parikh (PNP): I entered the printing industry in 1964. It’s been 50 years but seems like yesterday. It was not TechNova, but Printwell that I joined. It was a small letterpress print shop in Mahalaxmi in Mumbai. For me, the choice was to join the family’s printing company or its travel business. Travel had glamour and all the freebies that went along with it, but there was something in printing that grabbed me. That was creativity even in those days, perhaps more so in those days than now.

Printing is a mix of manufacturing as well as services, creativity as well as process orientation. So I made a commitment to printing. This also helped my brother, Jagdishbhai, who had started Printwell, and needed support as he was also involved in other businesses. It was all letterpress, and just beginning to get into offset. The greatest challenge for letterpress then was to get high-quality four-colour blocks (i.e. photo-engraved printing plates). You considered yourself lucky to get an appointment with Mr Nerker (Ashok’s father) or Mr Poonawala (Fred’s father), and you felt fulfilled if they accepted your job, and felt really blessed if the blocks were delivered in two months. It was a highly disorganised industry, and was in its infancy in terms of technology. But that was what made it more interesting. Printwell moved from letterpress, to offset, sheetfed and later web, with Sanatbhai and Manugraph’s RO-2 and Zircon.

RR: The lessons you learnt…

PNP: The one thing that I learnt during my journey after entering into offset printing was: if one wanted to be a high quality printer, good quality consumables were a must. And one of the biggest bottlenecks, apart from paper, was printing plates. In those days, offset plates were made from zinc. They were twice as thick as the current aluminium plates, grained and regrained in-house 15–20 times. It took 90 minutes to regrain. And another 90 minutes to coat, expose it to film positive and to develop the plate using a 10-step deep-etch platemaking process, after which the plate went on the machine. A two-hour set-up time with start-up waste of 200 sheets was considered “super”.

There was a 10% chance that the plate would fail. In which case, the machine waited while you prepared another plate. And there were other limitations such as poor dot resolution, registration, scumming, etc. And these plates were imported with a 195% import duty, from monopoly suppliers. The entire trade was in the hands of dealers, who managed the prices by creating artificial shortages.

RR: Who – and what – is the legend of Alan Vincent?

PNP: Luckily, when things are really tough, angels walk into your life. For me, it happened to be a British gentleman, Alan Vincent. It’s a story in itself. He was an accomplished printing technologist and a research scientist, who had left Kodak many years ago to give his life to Christ. He was in India as a lecturer at the GIPT (Government Institute of Printing Technology, Mumbai), and a consultant to printers like Vakils, GLS, etc. We were lucky that he agreed to be Printwell’s consultant for quality improvement. He told me that the Indian printers would never be able to improve their print quality and productivity unless they used factory-made electro-grained and anodised aluminium plates. So that was the inspiration for setting up TechNova in 1971.

RR: What were the hurdles?

PNP: Hurdles? The first one was technology. Like Sanatbhai, I went around the world looking for knowhow. No one was willing to trust us, an Indian company, with technology knowhow in those days. Based on Alan’s Vincent confidence that we could develop the knowhow and manufacture the aluminium plates ourselves, we started the project as an R&D journey. In our attempt to make tri-metal (base aluminium with layers of copper and chrome), we ended up making bi-metal (copper-clad aluminium) plates for photoengraving (=blockmaking). After two years of failures, the R&D team succeeded in making aluminium plates. The learning: no matter how long it takes, one needs to hang in there, stay focused and continue investing in R&D. Since then, the R&D culture has been embedded in TechNova’s DNA.

RR: What about the sourcing of aluminium?

PNP: The second hurdle was, how to procure litho-grade aluminium coils? Aluminium was, and still is, a monopoly industry. After persistent efforts, INDAL agreed, and succeeded in developing litho-grade after several painful years. The third hurdle was, how to get the printers to shift from zinc plates to aluminium plates? Zinc was the “in-thing”, aluminium for plates was unheard of. Luckily for us, Howson Algraphy, the global plate leader based in UK, had popularised aluminium plates around that time, which helped. Slowly, over the next two years, we put a lot of tech-support people in the field, and supported printers to try out the new technology. The quality-conscious industry leaders were the first target customers. They experienced a marked improvement in quality and productivity, and were quick to switch over. Once they adopted it, others followed.

RR: Good growth since then?

PNP: Thereafter, the growth curve for TechNova was steep. The final issue was of financing. When you invest in R&D without results, it drains the company. The grapevine in the company was: “Pranavbhai TechNova and Printwell, donoko dooba dega”. Luckily, thanks to supportive bankers, and “the Guy-up-there”, that did not happen.

RR: At Printwell, you worked on the RO and Zircon. What is your feedback about an Indian press, and your experience with a manufacturer like Manugraph?

PNP: Prior to the web presses, we were using Heidelberg, Roland and also an Indian manufactured press. The experience with the Indian press was a disaster. That created a negative image of Indian machinery manufacturers. But what worked in favour of Manugraph was their attitude, which was completely different from what we had seen in other Indian companies. It was totally customer-oriented and focused on engineering excellence. They supported us all the way. I believe we were one of the first commercial printers to enter web-offset printing. Manugraph technicians taught us how to do web-offset printing. One of the first four-colour commercial magazines to be printed by web offset in India, was on Printwell’s Manugraph RO-62 press. This was followed by the heatset. Manugraph’s Zircon, was the next logical step.

See All

See All