Upendrakishore Raychoudhury The Multifaceted Print Genius

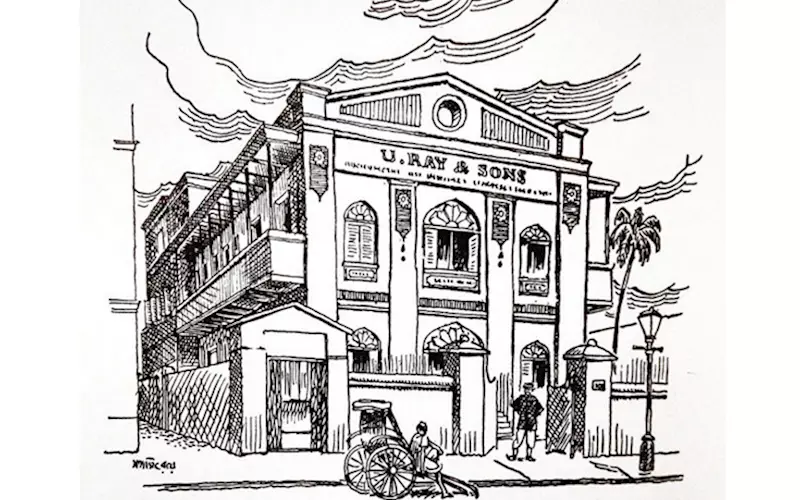

Kolkata-based Pratipranjan Ray brings to fore U Ray & Sons – the family press of the Rays – and shares gems about Upendrakishore Raychoudhury, a forgotten icon of the industry

11 Jun 2019 | By PrintWeek India

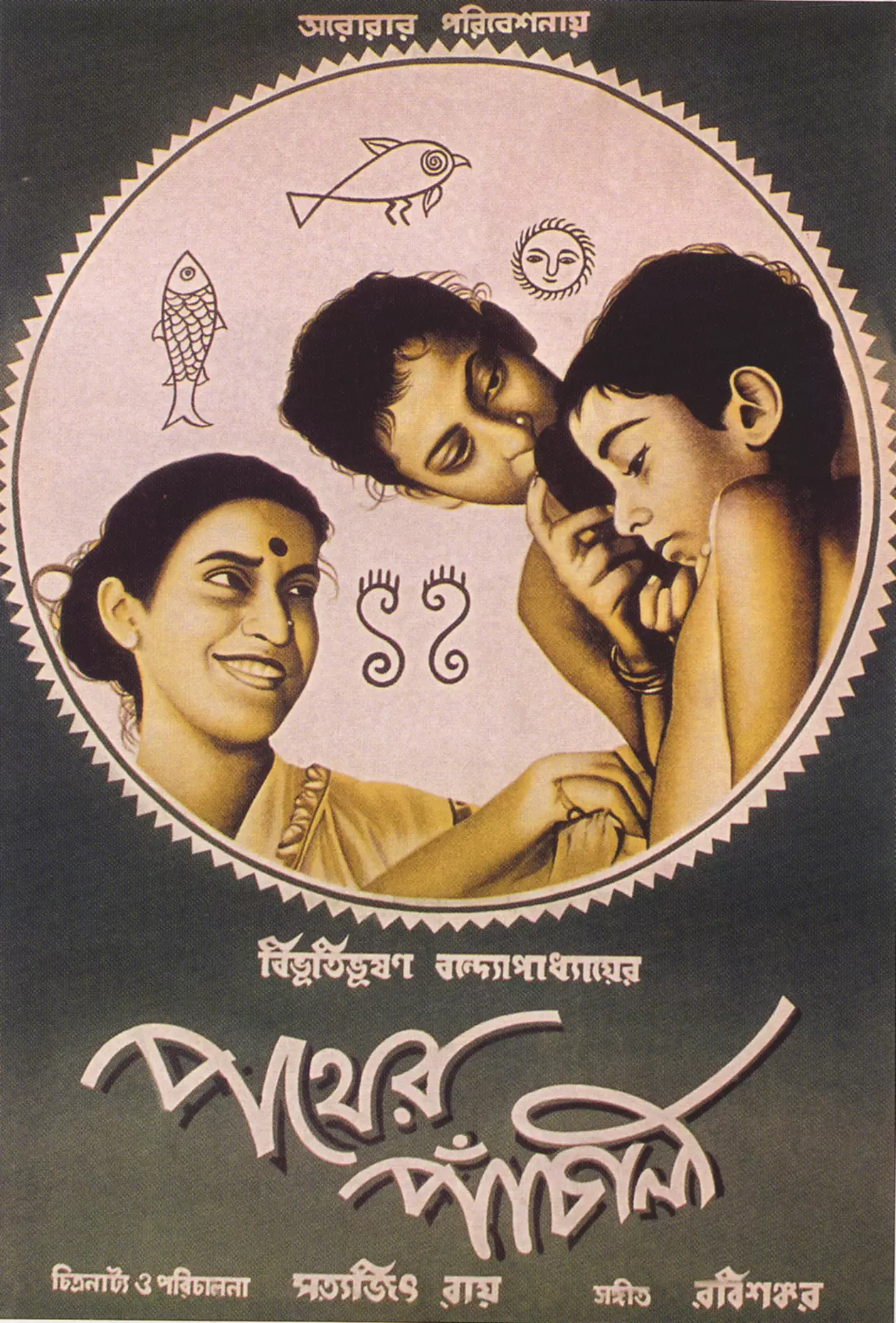

Some months ago, in an article published in PrintWeek, while talking about the development of printing presses in Calcutta (now Kolkata) in the 19th and early 20th centuries, I had mentioned U Ray & Sons without delving into the background of the company or its founder Upendrakishore Raychoudhury – Satyajit Ray’s grandfather.

Raychoudhury was a versatile genius whose legacy still carries on in West Bengal. Introducing him Satyajit Ray wrote, “Upendrakishore was a combination of scientific enquiry, artistic invention, and the best that art and literature had to offer.” He played the violin and pakhawaj and dabbled in the science of music while composing devotional songs. He indulged in photography and its science and conducted original research in printing technology. He wrote extensively for children and retold stories from epics. He painted and sketched innumerable pictures and looked into the heavens with his own telescope. For him, nationalism was a mission to be achieved through character building.

In spite of this versatility, Raychoudhury’s eminence, even in West Bengal, has mainly centred on children’s literature – storytelling and illustrations. But his contribution to the development of modern printing was monumental. Barring Shankar Awaji Vishal, Raychoudhury is the only Indian who has made an elementary and original technical contribution to the development of printing through his inventions on the process work and the process camera. He was an inventor par excellence and a master craftsman.

Formative years

Raychoudhury was born to Kalinath Ray (a landed title) and his wife Joytara in 1863, as Kamadaranjan Ray. Kalinath’s cousin Harikishore who had built up a zamindari in the district of Mymensingh (now in Bangladesh), and had expanded his surname to an aristocratic Raychaudhuri was childless even after two years into his marriage. Harikishore thus adopted Kalinath’s second son Kamadaranjan and changed the name to an awe-inspiring Upendrakishore Raychoudhury. In his own technical essays, Raychoudhury later wrote his name as U Ray.

Since his school days, Raychoudhury’s mind had an artistic bend but its full potential was yet to find expression. Passing out from his village school in Mymensingh, following the trend, a 16-year-old Raychoudhury travelled to Calcutta in 1879 to pursue his education at Presidency College. He later joined the Metropolitan Institution to complete his BA in 1884.

By the time Raychoudhury arrived in Calcutta the city had become a hub of social awakening and a centre of academic, literary, and artistic activities. It had begun to enjoy the fruits of missionary efforts put in by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, Pandit Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar and other luminaries. Rabindranath Tagore was blossoming into his future greatness. The Brahmo Samaj, though with a small number of members imbibing the liberal ideas of the West and East, was taking the lead in social reformation through character building. The idea of nationalism and the struggle for national identity was gaining ground.

Raychoudhury arrived in Calcutta within this milieu and lived with his old friend Gaganchandra Home, a staunch Brahmo. He married into another Brahmo family and converted himself while the rest of his family, including his elder brother – Saradaranjan, the father of Bengal cricket, remained in the old family faith.

The making of a genius

It was after coming to Calcutta that the many-faceted genius of Raychoudhury started taking shape. Even before his graduation, his first short story for children appeared in Shakha in 1883, bursting open the floodgates of literary creativity. It was followed by Shakha O Shathi and Mukul. Raychoudhury not only contributed to short stories but also wrote about the mysteries of science, illuminating the minds of the young. He supplemented these writings with his own illustrations.

The creative genius of Raychoudhury found its manifestation in music, too. While he composed a large number of songs, some of which are sung even now in the Brahmo Samaj, he was also a deft player of both the violin and harmonium. He explained the technology behind these instruments and their scientific nuances.

Since his college years, Raychoudhury took a keen interest in photography. Quite a few of his early writings contained photographs clicked by him, and few of these find place of pride in Penrose Journals. In fact, there is evidence that indicates he was toying with the idea of developing a camera for colour photography.

It was this passion for photography that propelled Raychoudhury to take keen interest and delve deeper into the science of the halftone process. He began with securing books and periodicals and instruments from the West. This gave him the scientific grounding for his expertise in the photo process. More about it, later.

Raychoudhury expressed a lot through his illustrations – drawings and paintings in both oil and watercolours. It was probably why the wooden and metal blocks of those days did not seem adequate to express his thoughts in his stories and books. He became conscious about this inadequacy while working on Chheleder Ramayana or ‘Ramayana for the young’ in 1897. This is when he started mastering the art of block making and the process of producing halftones. He started sourcing books and machinery from England to be able to do so in a short span of time.

Around this time, according to an advertisement published in a local daily, Raychoudhury was operating as a photographer and a block maker under the name

of U Ray, BA, Artist.

HALF-TONE BLOCK AND BROMIDE ENLARGEMENTS OF THE HIGHEST QUALITY ONLY

Halftone block from photograph etc At Rupee One

U Ray, BA , Artist.

38-1 Shibnarain Dass Lane, Calcutta

Another advertisement published in 1897 in Amritabazar Patrika bears testimony to the fact that he had honed his skills of producing halftones and was able to produce blocks with 75, 85, 120, 133, 170, 240 and even 260 lines or dots.

HALF-TONE BLOCKS

U. Ray begs to leave to announce that by his new method of half-tone engraving he is prepared to give results such as very few persons in the world have hitherto produced. He can now undertake to make half-tone blocks of the following fineness of grain:- 75, 85, 120, 133, 170, 240, 266 lines to the inch. The patterns he can produce are simply innumerable.

Price for the ordinary kind of grains up to 133 lines-

Zinc blocks at Re 1per sq.inch.

Copper blocks at Re. 1-8 per sq inch.

Price for more artistic work on the application to :

U. Ray, B.A, Artist

38-1 Shibnarain Dass Lane, Calcutta.

Both these advertisements stand testimony to Raychoudhury’s acquired expertise of producing high-quality halftone blocks.

However, Raychoudhury’s claim in the second advertisement, considering the availability of the size of the paper or the glass screen, seemed preposterous to a normal printer. He was eventually called to a judicial process to explain his claim. Though, if one were to look deeper into his claim, the mystery would be crystal clear.

By taking glass screens of 85, 120, and 133, with the help of a special process he was able to double each of these screen lines to make them into finer halftone presentation. In fact, Raychoudhury’s adeptness was such that he was not only able to double the lines but also increase the finesse by four times. His essay on the study of ‘How Many Dots’ was published by Penrose Annual in 1901; though four years earlier he had already implemented it.

Owing to Raychoudhury’s expertise in block making and halftone process, the people of West Bengal, for the first time, started seeing the paintings of the Western masters in books and periodicals of the time. Thus, a whole new world of art and creativity came within the reach of the common people.

However, his greatest achievement with regard to printing and print processing was the invention of the Screen Adjustment Indicator – a device to mechanically ascertain the distance of the screen. A photograph of this instrument was carried in the book The Half-Tone Process by J Verfasser and later Penrose Company patented the product. Prior to this, the exact distance of the light sensor or the film and the screen was manually set, making block making dependent on individual experience. The invention helped in the automated adjustment of the screen, which made it easier for an operator to adjust his process camera. Writing about his invention, Raychoudhury observed: “Anyone with good knowledge of photography can now make a negative with the help of a Screen Adjustment Indicator …………(with this apparatus) the average quality of work, on the other hand, will be improved, owing to the element of uncertainty being eliminated”. It was said that the apparatus freed the operator from making a personal choice about the matter.

All the studies, researches, and practical implementations vis-a-vis halftone photography, screen focusing, theory on dots, diffraction etc, resulted in a series of nine essays by Raychoudhury between 1897-1912 (two were added later) and were published in Penrose’s Pictorial Annual (originally known as the Process Year Book), a London-based publication on graphic arts. All these essays have now been published by the Jadavpur University in a facsimile edition Upendrakishore Roychowdhury – Essays on Half – Tone Photography.

Raychoudhury’s process work was acclaimed internationally. Process Work and Electrotyping magazine wrote, “Mr Upendrakishore Ray of Calcutta …………… is far ahead of European and American workers in originality. One British technical journal of his time had no hesitation in saying that Raychoudhury’s work on multiple diaphragms had a very important bearing on the future of halftone since it had brought the entire process to mathematical exactness.

Though his achievements in print processing were hailed internationally, he was denied patent registration. But he never expressed any bitterness over it and instead said, “To craft, it matters little who gets credit for a particular invention. What directly concerns them is the addition of a valuable resource to their equipment.”

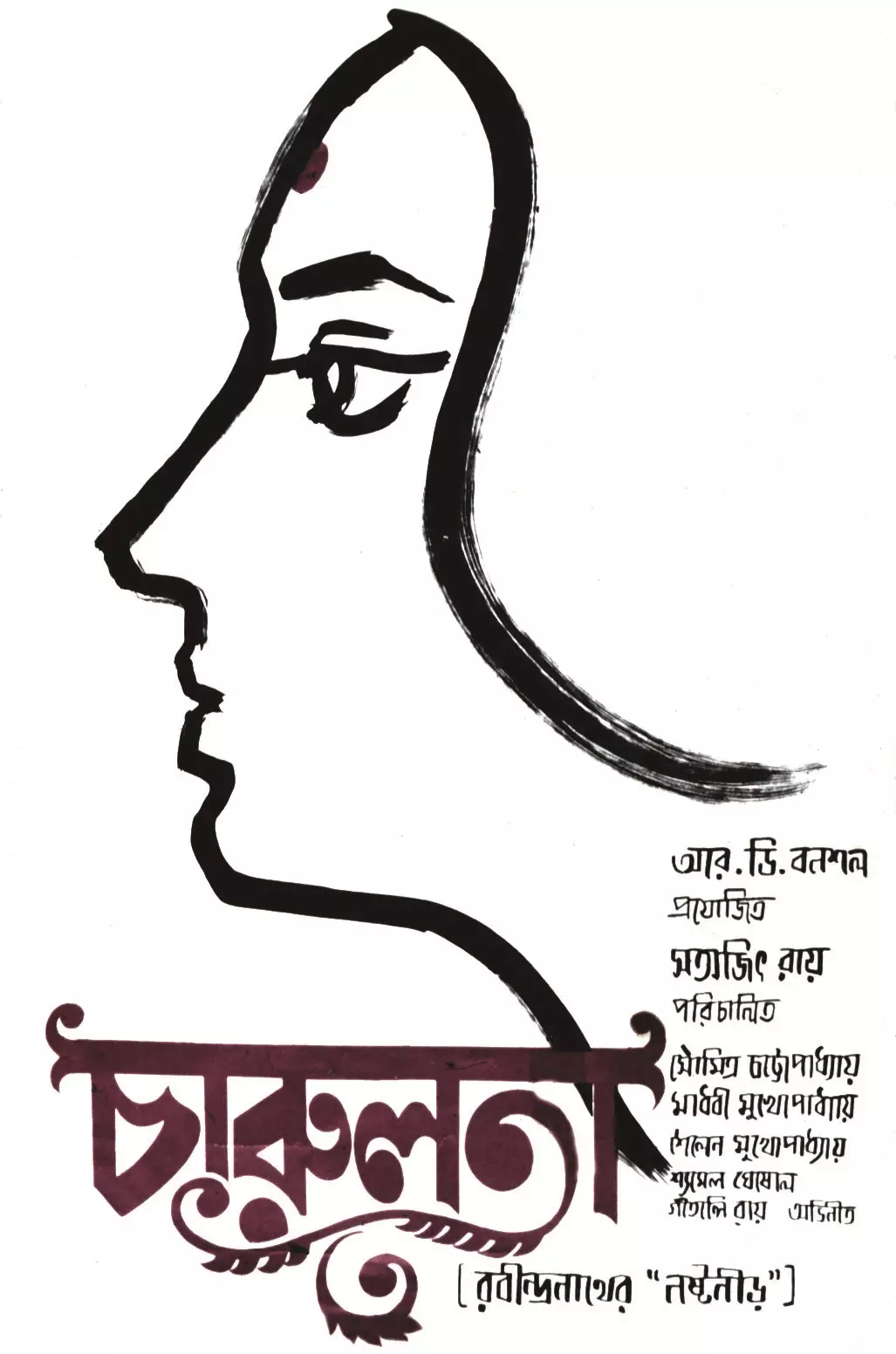

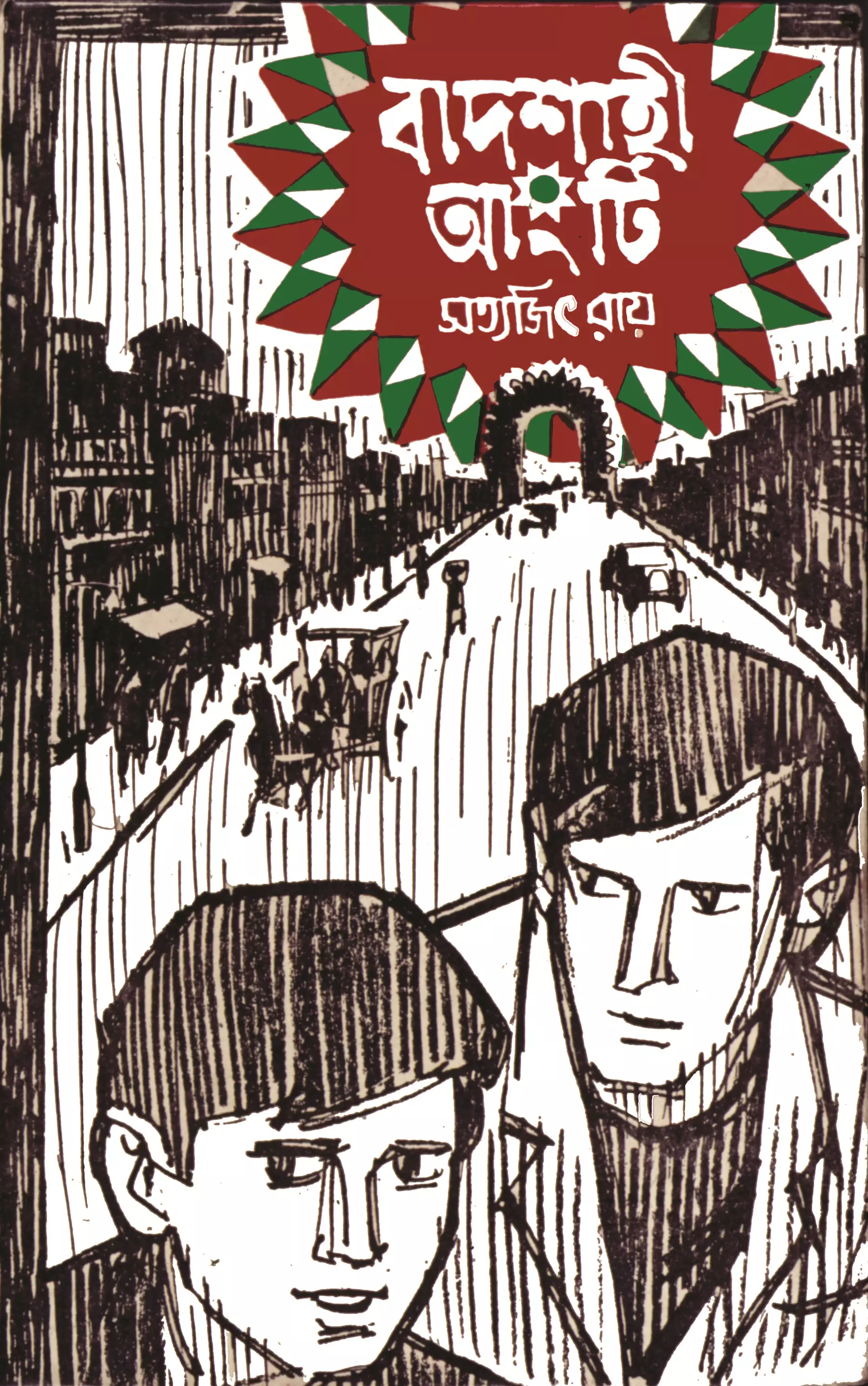

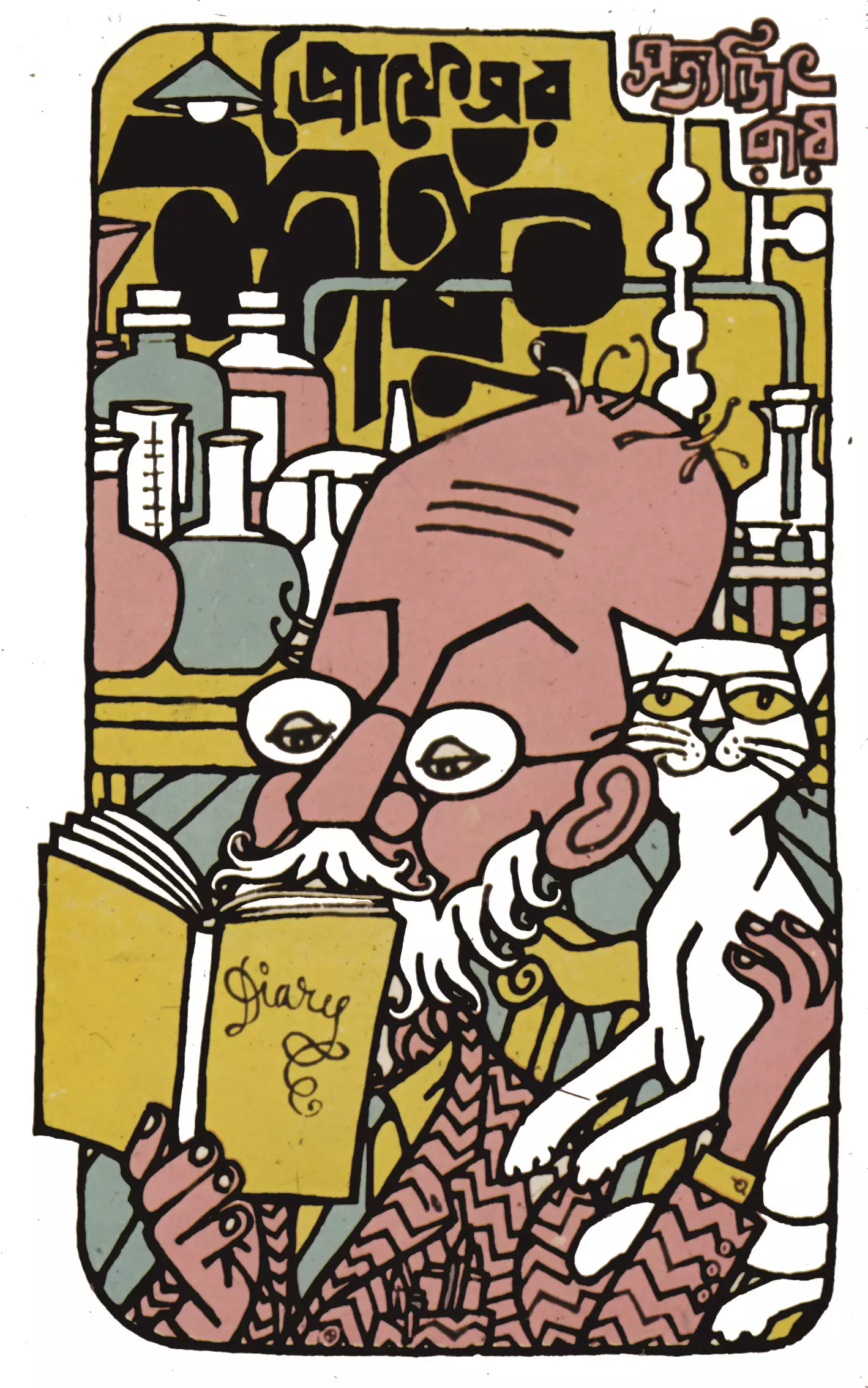

In 1910, Raychoudhury changed the name of his set-up from U Ray Artist to U Ray & Sons, a printing–publishing firm. That year saw the publication of one of his ageless book for children, Tuntunir Boi. Another of his creations, perhaps the closest to his heart, was the magazine for the children – Sandesh – first published in 1913. It was the only title for which Raychoudhury put on multiple hats of a creator, book designer, illustrator, poet, scientific inventor, block maker, storyteller, and musician. Within two years of Sandesh’s publication, Raychoudhury passed away, leaving an impact on the world of children’s literature in West Bengal. Sandesh continued to be published from the Ray household, albeit with a couple of interruptions, with Satyajit Ray finally taking up the editorial responsibilities.

Raychoudhury was an explorer, coloured with the aesthetic tinge of a painter, musician, and a storyteller. He was the bridge between sound, light and colour. While his artistic creations have lingered on among the young and old alike, his scientific and technical soundness have not been followed through, thus making Raychoudhury the only Indian who made any meaningful contribution to the world of printing and print processing.n

Pratipranjan Ray has served in the paper industry for over 47 years in various roles. Since the last few years, he has been imparting knowledge to institutes in the US, UK, Europe and China.

See All

See All