Shankar, CBT and the rise of children's books in India

When I was a little boy, every evening my father would read stories from the Panchatantra in Sanskrit, and tell me those tales of the animal kingdom in Kashmiri, my mother tongue. Exciting though those stories were, I remember snatching the book from my father’s hands very often, trying to find illustrations that would help me visualise the scenes that were narrated. But there were no illustrations, nor could I read the text for myself.

07 Sep 2016 | By Som Nath Sapru

Until the early 1940s, there seemed to be no books for children in local languages. The first in the genre was probably a translation of Alice in Wonderland in Tamil in the latter part of the decade. It was subsequently translated into other regional languages, and some authors even adapted it, ‘Indianising’ the names of characters and places, and even intertwining Indian mythological tales with the original story.

It was only in the 1960s that children’s books became both easily available and affordable. Illustrated books in easy-to-read language were first brought out by the famous cartoonist, the late Shankar. Initially, mythology, culture, tradition and values were the themes of these books. Shankar encouraged his team of writers to write about real-life happenings and blend fact with fiction, instead of merely confining themselves to folk tales and the imaginary world of fairies.

Shankar was encouraged in his mission to produce children’s books by none other than India’s first prime minister Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru. He was granted a piece of land in the heart of the capital, and also a sizeable amount as a loan to establish a Trust. Thus, the Children’s Book Trust (CBT) came into being in 1957-58. It was inaugurated by the then President of India, Dr S Radhakrishnan on 30 November 1965.

CBT, the pioneer publishers of children’s books in India, has set for itself an ambitious target to promote the production of well-written, well illustrated and well-designed books for children. It brings out books that are easy to read and easy on the eyes, including books that enable children to have a better appreciation of India’s cultural heritage.

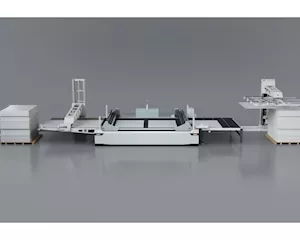

Shankar’s idea of having all writers, illustrators, editors and book designers, as well as print facilities under one roof, was unique for the times. In the 1960s he established the Indraprastha Press, from where all CBT books are published, produced and distributed until this day both in India and even in the international market.

Ravi Shankar, younger son of the late Shankar and one of the trustees of CBT, says the organisation produces at least four books a month. The bulk of the copies are procured by the government for reading rooms and libraries in rural and semi-urban areas. CBT also has its own sales points across the country. The affordability and the quality of the books make them very popular, he says, and was categorical that the books would continue to exist exclusively as printed matter, no e-versions would be produced.

Ravi’s involvement with CBT started because of his passion for printing presses from the time his father was actively involved in the publication of children’s books as well as the celebrated Shankar’s Weekly. Incidentally, the Weekly was the only ‘cartoon magazine’ of the time, and it was described as the Punch of India. It was launched by Nehru in 1948 but, sadly, publication was discontinued on 31 December 1975.

The popularity of CBT’s books inspired the Government of India to set up an autonomous body known as the National Book Trust in 1957-58, with the objective of producing and encouraging the production of good literature in English, Hindi and other Indian languages, besides children’s books, and to make such works available at moderate prices.

In 1993, the National Centre for Children's Literature (NCCL) was established by the NBT to monitor, coordinate, plan and aid the publication of children's literature in various Indian languages. NCCL was set up as a coordinating agency to promote children's literature in all the languages of India. It helps create and translate useful books for children.

Other children’s book publishers, like Chennai-based Tara, Tulika Books and Karadi Tales have expertise in translating children books. Penguin’s Puffin, DC Books’ Mango, Zubaan and Rupa’s Red Turtle have specialised in children’s books in English.

In the children’s magazine segment, the first to arrive on the scene was Chandamama in several Indian languages besides English and Hindi – followed by Champak, Amar Chitra Katha, Chakmak, Kishore (Marathi), Children’s World, Target, etc. The Urdu language has also contributed a lot to children’s books and periodicals – way back in 1893 Insha Alla Khan penned Rani Ketaki Ki Kahani, a humourous tale for children. Syed Imtiaz Ali’s Chacha Chhakkan stories are delightful reading for children. President Zakir Hussain also wrote for children, showcasing cultural pluralism, democracy and secularism, which are the defining traits of India, in very easy-to-read language.

Shama group’s Khilauna magazine for children in Urdu drew several well-known writers like Gulzar, Nusrat Zaheer, Raza Jafari, etc, who contributed well thought-out and crafted creations.

A landmark in the development of children’s literature was the establishment of a unique voluntary organisation The Association of Writers and Illustrators for Children (AWIC) in 1981 at New Delhi. The credit again goes to CBT’s Shankar. The AWIC is actively involved in the promotion and development of creative literature for children and also projects and promotes children’s book illustrators from India on international fora. Children’s book publishers have also utilised the talents of gifted authors, like Ruskin Bond, RK Narayan, Shankar, Manorama Jafa, Sarojini Sinha, Mulk Raj Anand and Kaveri Bhatt. Their works are contemporary stories where truth and fiction co-exist and are illustrated by expert artists and graphic designers.

In the Indian publishing industry, children’s books other than textbooks is a continuously growing segment, reportedly burgeoning at the rate of 14-18% vis-à-vis the publishing industry on the whole.

The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry estimates the annual turnover of the Indian publishing industry in 2012-13 at around Rs 1,000 billion, with the growth rate at 30%.

India is the third largest English language publisher in the world and the children’s book segment accounts for a quarter of this. Looking at the growing literacy rate, Indian publishers are pumping more investments into the industry and enhancing their trade by using new technology. One fourth of the 1.28 billion population of India belong to the youth and children’s segment, constantly in need of reading material, books and textbooks – and so it seems that the Indian children’s book publishing industry is facing a rosy future, with enhanced business and readership.

See All

See All