A brief history of the evolution of bookbinding

Book, as we see it today, is an important and effective conduit of interaction between readers and authors. And it’s in constant evolvement which is on-going. Prior to the evolution of the printing press, made popular by Gutenberg’s Bible, binding of the book was almost unknown. Before Gutenberg, any text on any subject was unique hand-crafted object, with design and features incorporated by the scribe, the owner, the writer or the compiler or the illustrator. It was done on individual sheets of loose paper put together by strings or wrapped in an oversized piece of cloth.

17 Oct 2020 | By PrintWeek Team

The evolution of bookbinding has a long and unique history dating back to 30th century BCE —when humans developed writing skills. Soon the scholastic activities of copying in multiples, comparing, and archiving of texts by various authors, and other related activities started to become more professionalised and compartmentalised — initially starting in Egypt.

First, the paper

In the Asian continent, it was China where we can trace recognisable books, called Jiance or Jiandu and these were scribed on rolls of thin split and dried bamboo, bound together with hemp, silk or leather. The discovery of the process using bark of mulberry to create paper is attributed to Ta’sai’lun but it may be earlier than that.

In our country, most of the written scripts were traced on rocks which originated during Ashokan (Maurya) period dictating religious and state edicts. Later on ‘tamrapatra’ — thin copper sheets, and followed by ‘burjapatra’ — bark.

In the southern part of our country, ‘tada’ or ‘tala’ or ‘tali’ — palm leaves —were widely used for writing of manuscripts. They used to keep these leaves together with a cord going through all these leaves by a hole right in the middle of these leaves containing the manuscript.

Until recent times, children were made to learn writing skills either on a smooth, small piece of a wooden plank 8x12-inhces in size known as patti or takhti, with washable India ink or on a thin black stone 8x12-inches size known as slate with a soft chalk, which was prevalent mostly in Northern parts of the country.

In certain parts of West Asia, up to medieval times, animal hides known as vellum were used to write, but in our country it was pure no, no. The Greeks used leather predominantly to inscribe land and government records. The Greeks rolled these hides and stored them in the racks with cubby holes.

Around 7th and 8th century, in India, non-porous cotton cloth, glazed with rice starch, was used to record the manuscripts — which continued till recent times, used by architects and engineers to record their drawings and maps for safe keeping. It is known as tracing cloth. This method of writing was prevalent in India till the end of 10th century or the beginning of 11th century AD.

It was in China where the beginning of paper fabrication started in the then concentration camps which was later transported by Arabs with Chinese prisoners of war to Samarkand in early 751 AD. The fabrication was done with old linen, flax or hemp, based on the same technique and methodology as used in China. Over the years, the Arabs improved the fabrication technique.

During that period, there was lot of commercial activities between India and some of prosperous Middle Eastern countries and it is through that route, Khurasani paper and its fabrication arrived in our country via Sindh after its conquest in the 8th century — that too in Kashmir.

The fabrication was continuously improvised and it became a profit-making activity and later diffused to most important cultural seats during Sultanate period —Delhi and Lahore.

Undoubtedly, the Arabs improved on the quality of paper vis-à-vis the Chinese product as they supplemented linen, flax and other vegetable fibres, but in Kashmir, the paper quality was further improved and finished during the time of Sultan Zainul Abedin between 1417 and 67.

Well, since the base material for writing activities became easily available and authors of various texts observed the foldability of the base material compared to Bhurjapatra or Tadapatra, and also that it could sustain thread as part of gathering number of sheets of paper together, it soon became widely acceptable.

The handmade paper, normal as well as glazed, was a remarkable product of medieval India. Bark and Talpatra (palm leaves), silk and cotton cloth were essential ingredients of fabrication of this paper. The product was not only used in India but also exported to other countries.

Beginning of binding

Now, let us see what was the binding scene at that time —the process of physically assembling a manuscript from an ordered stack of papers, or Bhurjapatra or Tadpatra or paper which was known as ‘kagaz’ that were folded twice once in oblong side and next fold at vertical side into manageable sections and put in sequence and gathered together —ready to get bound together along with one edge by either sewing with thread through the folds or by application layer of flexible adhesive.

No one at this stage knew any other techniques of binding, which kept on evolving. It was and it still is an artistic craft of great antiquity, but it has become highly mechanised industry in modern times.

The divide between craft and industry is not as wide as one would imagine. For any mass production quantum of any print product, the problems faced by binding the craftsmen in medieval times or the modern mechanised production houses are the same. This includes, one, how to hold together the pages; two, how to cover and protect the gathered pages after they are held together; and three, labelling and decorating the protective cover, either soft or hard.

In the late medieval times, craftsmen over a period of time perfected the art of binding, by trials and errors. Initially, thick and heavy with fibre mixture papers were used for covering the gathered stack of pages bound together either by thread or flexible glue. The spine of these gathered pages were smoothened either by striking on to levelled and hard surface or slowly hammered by a smooth wooden bulge and then thick cover paper was drawn on the gathered and bound pages.

The initial growth of mechanising binding process was very slow, but it took roots in Europe in the beginning, when Gutenberg printed the first few copies of the Holy Bible.

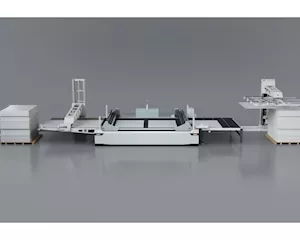

In today’s scenario of binding, modern book binding is divided between hand binding by individual craftsmen working in a bindery shop and commercial binding, mass produced by high speed machines like folding, gathering, initial stacking, perfect-binding with soft or hard cover application facilities and online cutters with trimming and bundling facilities, in a factory.

There is a broad grey area between the two divisions. The size complexity of a bindery shop varies with the job types being bound, for example, from one of-a- custom jobs, to repair/restoration work, to library rebinding to preservation binding, to small edition binding, to extra binding, and finally to large publisher’s binding. There are cases where the processing, printing and binding jobs are combined under one roof.

For jobs with large print runs, commercial binding is more advantageous for an effective production quality runs of ten thousand or more in a regular factory.

As said earlier, initially sewn binding was more acceptable, effective and durable, but undoubtedly, it was more cumbersome and time-consuming for large print runs. However, over a period of time, mechanisation slowly came on the scene, initially by wire stitching by hand drawn devices like modern staplers. It was further improved in the form of saddle-stitchers. Mostly saddle-stitchers were used for centre-stitched jobs and it had a limitation of certain number of pages in a book or any publication and the publication with more number of pages could be side-stitched very close to the spine. But the problem with this type of bound publication was that it couldn’t open layflat well, like centre-stitched publication. Well, this problem was resolved with spiral binding which could open layflat irrespective of number of pages. But this type of binding didn’t have much of a shelf life vis-à-vis centre stitched or side-stitched publications.

Around 1868, David McConnell Smyth patented the first sewing machine, which was created for bookbinding. The system and the technique of sewing through the fold of each signature to create a strong and well-gathered binding is still used and is well recognised as Smyth sewing.

Well, this kind of sewing for the perfect bound books and publications was further improved, which became a part of perfect binding machines of modern times. Here, Germans excelled in the manufacturing of binding, as well as printing machines.

Besides binding machines, they started with letterpress machines and excelled in it too and later around the beginning of 19th century, they came up with successful offset machines.

In India, it was Srinivas Reddy based in Bangalore who created India’s first single-clamp perfect binding machine in 1998 and marketed in 2000 under the brand name Megabound. This was followed by many other binding machine manufacturers like Acme; Welbound; Pramod Engineering, among others.

See All

See All