If you really want to read, there's nothing that can stop you from getting the right content. Payal Khandelwal tracks four ventures which are making sure that Indians read.

The more that you read, the more things you will know. The more that you learn, the more places you’ll go. — Dr Seuss

Well, it’s really as simple as that! No reading means a direct plunge into the cultural wasteland. In the Indian context, though, reading is easier said than done. There are privileged reasons like no time to read or there are no good libraries and bookstores around or that we live in an age of highly fragmented concentration. And for a majority of people in rural India, there are more humble reasons like not having any access to books and magazines, until at least a few years back.

But whatever our collective obstacles might be on the bridge to the magical kingdom of reading, each one is slowly being removed by a few unique distribution and subscription

ventures.

Four such ventures that are truly spicing up the reading game in India (and outside India as well) are Daily Hunt, Paper Planes, Mera Library and Grantha Tumchya Dari.

While Paper Planes and Grantha Tumchya Dari Library are promoting reading through the tactile print form, Mera Library and Daily Hunt are effectively leveraging the digital boom in India to reach the deepest corners of the country. Collectively, however, they all have a common goal - making sure that Indians read, and that they read well.

Here’s a lowdown on each one of them:

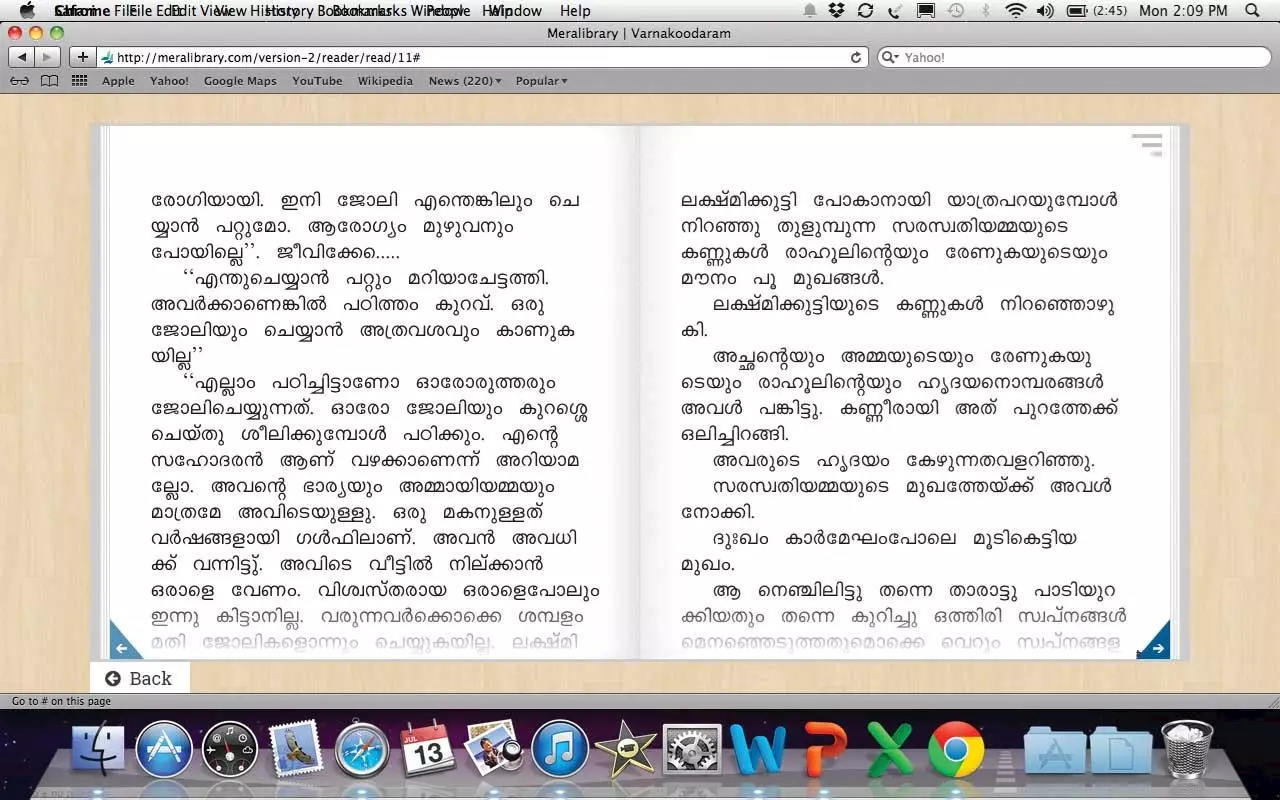

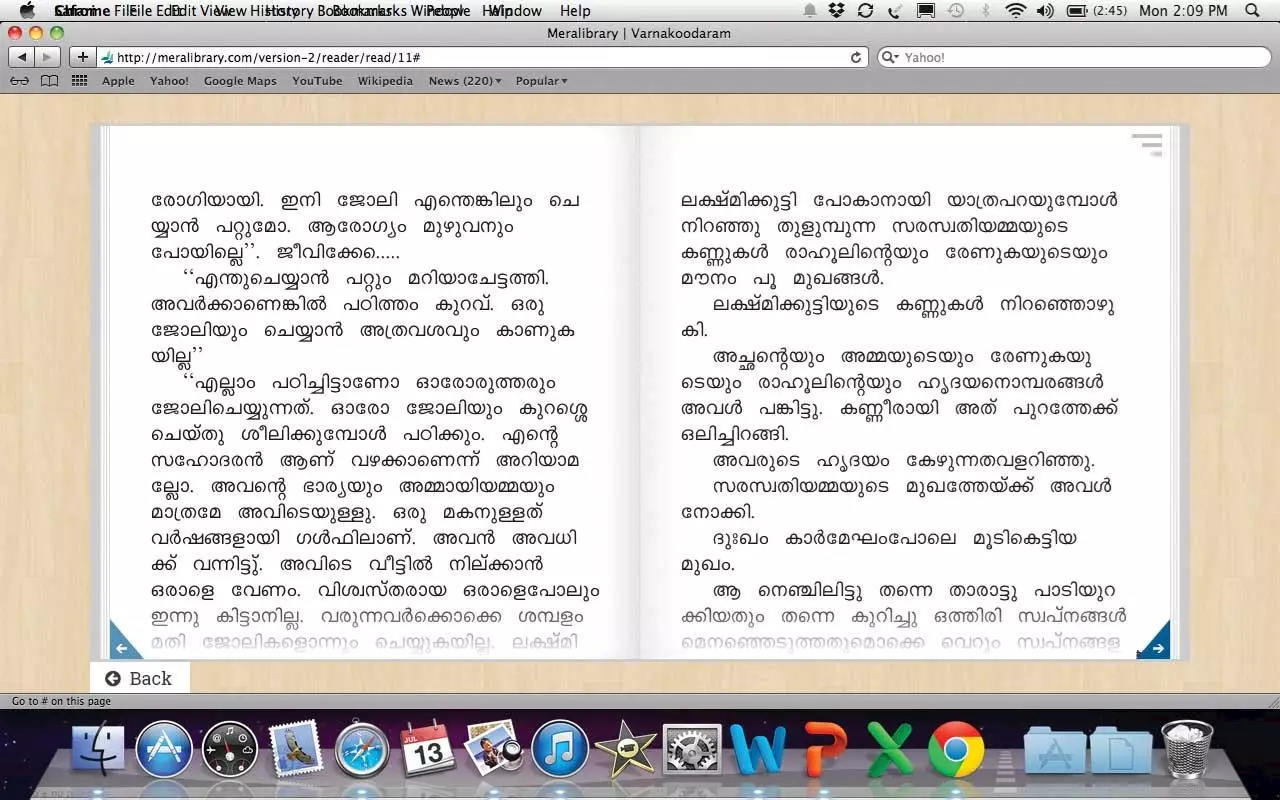

Mera Library

Mera Library was started in 2011 by Shabir Musthafa, CEO, Marmam Publishing, to give vernacular languages of India a web-based platform, to leverage the drastic changes in publishing worldwide. “Readers were starting to access books on their mobile devices, and the environmental and cost benefits of the eBook were obvious. Indian language publishing, vast in number of languages and literary output, required the best in technology and mobile strategies, and Mera Library was launched to assist in the discovery, rental and sales of their content,” says Musthafa.

The digital library functions like a normal, brick-and-mortar library where members take a membership and borrow books. There are time-based and language-based options for the readers to select from. The publishers, on the other hand, gain royalty from the revenue earned from the rental or sales of their titles from the library.

Mera Library’s target audience is readers of Indian language literary content worldwide. However, tier two-three towns and rural India are the prime users of the platform. Musthafa believes that changes in the Internet connectivity will give the rural users the ability to access content, in their own languages and on their mobile devices. There are about eight Indian languages available on the platform. And the future plan is to partner with publishers and authors from the states in the North- East.

Mera Library is currently undergoing an overhaul exercise to offer a better and more responsive mobile experience for readers since they believe that more reading will happen on the mobile rather than the desktop. They will also have mobile applications for Android and Apple that will allow for offline reading as well. One of the biggest learnings so far, Musthafa says, has been the understanding of the specific mobile publishing technology needs for Indian languages.

The library includes books in different genres, including many classics in regional languages. The most-read books on Mera Library are children’s picture books in multiple regional languages. There is also a robust readership for cartoon books, especially in Malayalam.

The overall future of eBooks in Indian regional languages is extremely bright, feels Musthafa, due to continuous and increased penetration of mobile devices. “The eBook has the ability to reach out to readers everywhere. If national and governmental vision teams up with private enterprises, we will see great days for publishers and authors in Indian regional languages,” he says.

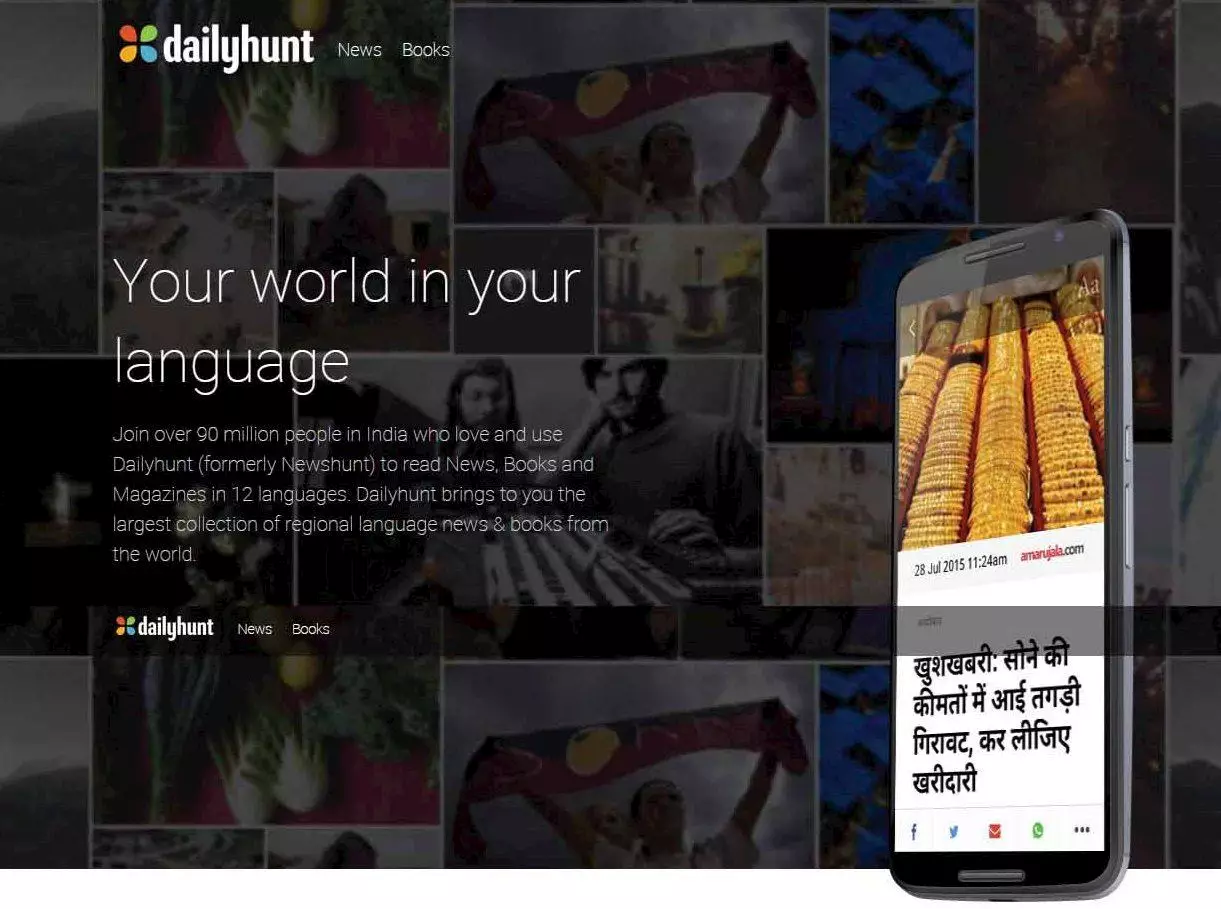

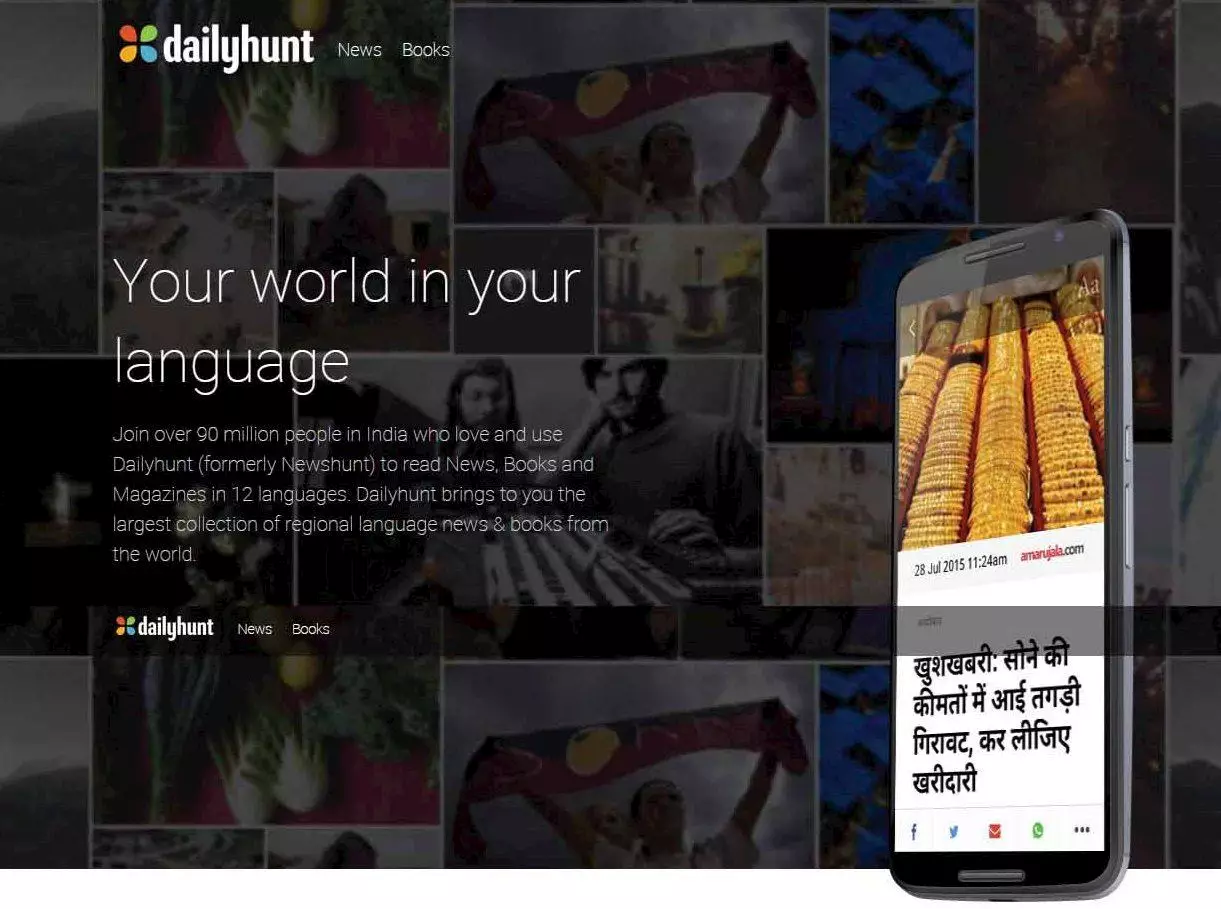

Dailyhunt

Dailyhunt (formerly Newshunt) is equally upbeat about the prospects of eBooks in India. A local language news and eBooks platform, Dailyhunt is currently used by over 100 million people across 15 languages. According to the statistics provided by Dailyhunt, it gets over 2.7 billion monthly news page views, and since launch of eBooks in 2014, it has had more than 26 million local language eBooks downloads.

Talking about its inception, Vishal Anand, chief product officer, Dailyhunt, says Indian content has so far struggled to get online traction because of non-standardised tools of content creation, and no support for Indian languages on devices (desktop as well as mobile). Publishers are creating content mostly for print, using non-standard font.

“And when they try to put it in a digital form - unless the client device has the same font available - the content will not get displayed. Even if the content is created in standard unicode font, 95% of phones available in Indian market still don’t support one or more Indian language. Dailyhunt was created to solve exactly this problem - to get all forms of written content (digital as well as physical books) standardised for consumption,” he says.

The platform currently offers news, eBooks, videos, magazines and comics, and is working towards building a platform which will host content in different formats and for local language users. Like Mera Library, Dailyhunt’s vision is to mainly target the population in tier two-three and rural parts of India which can easily access content on mobiles, provided it’s available to them in local languages.

Dailyhunt has also struck an alliance with Graphic India to provide graphic novels to its users. There are currently more than 300 titles of Graphic India available on the platform, of which 250 are in Hindi, Telugu and Tamil. The overall sales happen across genres, says Anand. Pulp fiction, short stories, self-help, and health, mind and body are some of the popular categories. For eBooks, readers also have the option to purchase one chapter at a time instead of the whole book.

For more inclusion of readers who don’t have access to credit or debit cards, Dailyhunt allows purchasing of content (except subscriptions) through mobile payments. “With a country with only 2% credit card penetration and most not even having a bank account, mobile payment is the only viable mode of payment online,” feels Virendra Gupta, CEO and founder, Dailyhunt. “Today, our solution reaches over 850 million customers via Airtel, Vodafone, Idea, Aircel and Reliance, with flexible price point ranging from Re 1 to Rs 500.”

Granth Tumchya Dari

There are currently 600 bags, each full of 100 books in Marathi language, circulating in different regions of India. Granth Tumchya Dari (GTD) is an initiative started in 2009 by Vinayak Ranade, trustee of Kusumagraj Pratishthan (an organisation to felicitate the late Marathi poet and author VV Shirwadkar alias Kusumagraj). GTD basically works like a free mobile library, located inside these bags, travelling from one place to another.

Kusumagraj Pratishthan had a pretty decent library but barely any readers. “People in general weren’t reading much at that time (around 2009), due to time, availability and reach issues. And that’s when I thought that if books could land up at readers’ doorstep just like any other utilities, they would read,” says Ranade. To kick off the initiative, he first contacted his own personal network. He asked people he knew to donate whatever they can to start so that he can invest the money in buying new books. Soon donations started pouring in, some as large as Rs 15 lakh from a friend in the US, and the project started in Nashik, Maharashtra, with 11 bags of 1,100 books.

The model was simple. Each area, comprising 35 members, gets to keep the bag for about four months during which they exchange the books with each other every once or twice a week. All the bags contain different books, which are either Marathi literature or literature translated in Marathi.

After starting GTD locally and also distributing the bags in places like jails, hospitals and industrial areas, Ranade decided to spread out GTD to other regions in India, including the rest of Maharashtra, Delhi, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, etc. In different places, for distribution, he started involving cooperative banks or other such institutions by giving them advertising (done with stamps) in the books’ pages.

In fact, the donors are also gratified in a similar way, by having their names stamped on the pages of the books. Under the model of GTD, the books are made available through monetary donations towards Kusumagraj Pratishthan and are available to readers free of cost.

GTD now has two more subsets, which are targeted at individuals and are paid for by the readers themselves. Majhe Granthalaya (My Library) aims to create small reading groups in a city. Each individual gets a bag of 25 books which he exchanges with other readers usually during a monthly meet. Another similar group is for children (second to eighth standard) where each bag has 25 books with 15 Marathi storybooks and 10 English storybooks.

Interestingly, GTD also caters to the Marathi reading population in Dubai, The Netherlands, Tokyo and most recently in Atlanta (the US). The total number of readers is now above 30,000.

While GTD limits itself to Marathi, Ranade says he is more than happy to help anyone else use his model for other languages.

Paper Planes

Paper Planes, started by Nupur Joshi-Thanks, who earlier worked in a corporate law firm, gets independent niche magazines from across the world to the Indian market.

People can subscribe, select their choice of genre and get a new indie title every month for a fixed cost, or buy any title of their choice from the online store.

Talking about the backstory of Paper Planes, Joshi-Thanks says, “Sabbaticals are known to have done wonders for people – and I owe this steady ‘descent’ into magazine madness to my sabbatical too. I have always been fond of reading magazines, but these magazines were not like the others. They seemed more real. You know, real stories for real people, unlike the fanfare based, celebrity obsessed, product toting publications that are crowding the local bookstores. I found myself hoarding one magazine after another, fascinated with the passion driven content and really high production value,” she adds.

Paper Planes has been getting indie titles in different genres from locations as varied as Beirut, Berlin, Amsterdam, Australia, Barcelona, Finland, US, UK, etc. In most cases, the sourcing of magazines is done directly from the indie publishers themselves, as opposed to distributors. This obviously helps in cutting down the cost to a certain extent.

It is now also focusing on providing an active platform for our very own indie magazine makers. She says, “I discovered that there were a few early adopters of this new age print in India, who are doing an amazing job, like Gaysi Zine (a magazine for the queer people), Kyoorius (a magazine of visual culture), White Print (a lifestyle magazine in braille), etc. This reaffirmed my faith in the changing face of print and its undeniable impact on the cultural framework. I am excited about the opportunities that lie ahead and hope to see many more such resilient, fresh and engaging titles to be released here in India.”

Targeting mainly urban Indians, Paper Planes doesn’t want to only be a distribution platform though. It aims to create a community for indie magazine makers and like-minded readers in India.

And through its blog, it tries to connect the readers with publishers and magazine makers by introducing new titles, and by talking about the teams and work that goes behind indie magazines.

The digital library functions like a normal, brick-and-mortar library where members take a membership and borrow books. There are time-based and language-based options for the readers to select from. The publishers, on the other hand, gain royalty from the revenue earned from the rental or sales of their titles from the library.

The digital library functions like a normal, brick-and-mortar library where members take a membership and borrow books. There are time-based and language-based options for the readers to select from. The publishers, on the other hand, gain royalty from the revenue earned from the rental or sales of their titles from the library. Mera Library is currently undergoing an overhaul exercise to offer a better and more responsive mobile experience for readers since they believe that more reading will happen on the mobile rather than the desktop. They will also have mobile applications for Android and Apple that will allow for offline reading as well. One of the biggest learnings so far, Musthafa says, has been the understanding of the specific mobile publishing technology needs for Indian languages.

Mera Library is currently undergoing an overhaul exercise to offer a better and more responsive mobile experience for readers since they believe that more reading will happen on the mobile rather than the desktop. They will also have mobile applications for Android and Apple that will allow for offline reading as well. One of the biggest learnings so far, Musthafa says, has been the understanding of the specific mobile publishing technology needs for Indian languages. Talking about its inception, Vishal Anand, chief product officer, Dailyhunt, says Indian content has so far struggled to get online traction because of non-standardised tools of content creation, and no support for Indian languages on devices (desktop as well as mobile). Publishers are creating content mostly for print, using non-standard font.

Talking about its inception, Vishal Anand, chief product officer, Dailyhunt, says Indian content has so far struggled to get online traction because of non-standardised tools of content creation, and no support for Indian languages on devices (desktop as well as mobile). Publishers are creating content mostly for print, using non-standard font. People can subscribe, select their choice of genre and get a new indie title every month for a fixed cost, or buy any title of their choice from the online store.

People can subscribe, select their choice of genre and get a new indie title every month for a fixed cost, or buy any title of their choice from the online store.

See All

See All