A lesson to learn: Telgi and his counterfeit empire

Counterfeit is on the rise. Last two months have seen massive seizures of counterfeit currency notes of Rs 2,000.

Telgi masterminded the fake stamp paper scam thanks to his innate understanding of people's weaknesses and the government machinery. Telgi is no more, but lessons have not been learned.

In this Sunday Column, we discuss how the fight against counterfeit is not over.

03 Dec 2017 | By Noel D'Cunha

A few years ago, I was in Teddington for a Haymarket training programme. During a wine and dine evening someone mentioned how members of a family who ran a Birmingham print firm were jailed for 23 years after being found guilty of printing around USD 1.5-mn worth of fake ten-pound notes, in what was described as "an extremely sophisticated operation".

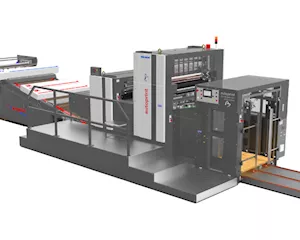

When I dug deeper, I found the sophisticated equipment was: a used Komori Lithrone S26 and a Heidelberg platen along with rudimentary computer kit with basic software.

Interestingly enough, the names of the counterfeiters were all Indians. There were the siblings Amrit and Prem Karra, owners of Hockley-based Karra Design and Print who were sentenced to seven years at Birmingham Crown Court, while brothers-in-law and colleagues Rajiv Kumar and Yash Mahey both received four-and-a-half-year jail terms for conspiracy to make counterfeit notes.

The four men bought special inks, foils and paper to use with printing equipment at what was a legitimate, family-run business, to print high-quality fake notes.

This reminded me of another "sophisticated counterfeit crime-master": Abdul Karim Telgi.

Telgi's modus operandi

On 25 October, Abdul Karim Telgi, who was convicted in counterfeit stamp paper scam, passed away in Bengaluru due to multiple organ failures. He was 56 when he died; the last 13 years of his life was spent in prison.

He was serving his term in Parappana Agrahara Central Jail in Bengaluru after being sentenced to 30 years of rigorous imprisonment in the multi-crore fake stamp paper racket. A whopping fine of Rs 202-crore was also imposed on him.

His crime: he printed "real" fake stamp papers.

The modus operandi was simple.

Employees of the Nashik Security Press (the top security government press which prints our currency) were part of Telgi's blueprint. The press discards old machinery. A new press is purchased on expert audits and tech specs.

Interestingly, a lot of the old presses (and plates) were declared "worn and torn". These were auctioned off as part of the government process.

The presses were purchased by Telgi and his tribe. It was stage-managed and pre-planned. The plates which were to be destroyed as per the rules and regulations was mounted on the press and sold. And so, at the end of the day, Telgi owned printing plates and printing presses for the printing of genuine stamp papers.

The stamp papers were printed during the night shift at Telgi's legitimate press in Mumbai which produced wedding cards and business cards. The stamp papers which were printed were loaded into dummy corrugated boxes and shifted by tempo-vans and vehicles with marked license plates to a bungalow in Nashik. An intrepid journalist who was tipped off by a political opponent of one of Telgi's mentors discovered bags and bags of ‘real’ stamp paper plates.

As Basant Rath, a 2000 batch IPS officer who belongs to the Jammu and Kashmir cadre, states, "While a case of fake stamp paper was registered in 1991 and another in 1995, the Maharashtra police officers investigated the cases in the most casual way, and Telgi got away. Although his racket was busted several times, he managed to escape the police dragnet many times.

In an affidavit, additional commissioner of police (ACP) Sanjay Bharve asked why, in spite of 27 cases of cheating registered against Telgi, he was never taken in.

However, with mounting public pressure and judicial intervention, the Maharashtra government constituted a Special Investigation Team (SIT), and Telgi’s run came to an end in 2001."

The point to note is: Had it not been for public pressure, Anna Hazare’s public interest litigation (PIL) and the court’s insistence on an investigation, Telgi’s criminal syndicate might have been swept under the carpet.

As a nation, we are very forgiving of white collar crimes.

We continue to be.

Telgi's crime syndicate

Telgi's claim to fame rose when he "showered as much as Rs 93-lakh in one night on one bar girl in a dance bar in Mumbai." The lower-middle-class boy who had lost his father at a very young age had arrived on the scene.

So? Who was Abdul Karim Telgi? A printer? Or a multimillion rupee scamster? Or the man who carried the visiting cards of VIPs in his back pocket?

After he was arrested, the investigation agencies discovered that Telgi ran the business like a corporate company by recruiting more than 350 agents, who sold the duplicate stamp papers of multiple denominations in bulk to banks, insurance companies, stock brokerage firms and MNCs.

When Telgi was arrested, the security and intelligence agencies estimated the size of the scam was a mind-boggling figure of up to Rs 20,000 crore.

As Basant Rath says, "The fact that Telgi could infiltrate India’s closely guarded security press so extensively and for so long is a reflection of the way our intelligence establishment (both revenue and security intelligence) works. Telgi was able to bribe insiders to obtain production programmes of the India Security Press (ISP) in Nashik. He knew what category and denomination of papers were being printed and sent to the market at any given time. He was able to buy special printing machines from the Nashik press which had supposedly gone beyond their shelf life, and were meant to be destroyed and sold as scrap. He bought them as scrap (at an auction which was fixed in his favour), but he was able to ensure that the presses were not destroyed, as they were meant to be."

Telgi: the small-town lad from Khanapur in Belgaum, Karnataka, who sold peanuts at railways stations in the 1980s to make a living, may be dead. But his tale continues to be reincarnated all over India with surprising operational ease.

Fakes currencies continue to thrive

This type of syndicate is still alive and kicking.

Post demonetisation, the government withdrew the Rs 500 and Rs 1000 notes. Simultaneously, they launched a new Rs 2000 notes which no one could replicate.

Last two months have seen massive seizures. The Delhi Police intercepted a consignment with Rs 6.6-lakh in counterfeit currency notes. Intelligence officials said, "while one of the objectives of demonetisation was to curb fake currency, the inflow of “high quality” fake Rs 2,000 notes has picked up again."

And so, between August and October, the Directorate of Revenue Intelligence has seized “high quality” FICN of face value Rs 35-lakh in the two new denominations, in three separate cases in Mumbai, Pune and Bangalore. These notes have eight of the 17 security features printed by the Reserve Bank of India.

The paper, the texture and the tech specs and hidden features have been replicated.

How?

Conclusion

On 30 November 2017, the one-rupee note completed a century.

The Government of India had issued banknotes for the first time in 1861, but 'One Rupee' as a promissory note was first introduced on November 30, 1917. It was printed in England and depicted a silver coin image of King George V on the left corner.

It is a good time to pay heed to the cautionary words of Basant Rath. He says, "If the structural loopholes that helped Telgi and his political and police mentors and partners in crime make a mockery of the might of the Indian state go unattended, there will be consequences. And India’s national security will not be the only casualty. It is a time we exhume the remains of the fake stamp and stamp paper scam and make the state machinery accountable."

As the print industry, we have to take a pledge: People looking to acquire equipment for counterfeiting may now increasingly contact private sellers rather than larger companies, which are more likely to be aware of the law and highly unlikely to take the risk of knowingly supplying equipment for illegal use.

Although counterfeiters will inevitably continue to find ways and means of making money from forged documents and cards, we must be watchful.

Beware: Especially, of the inside job.

How to spot suspicious customer behaviour

Acts unusually/suspiciously

Makes a cash purchase

Doesn’t question the price

Doesn’t require an invoice

Requires goods immediately

Collects the equipment personally

Provides no company name

Doesn’t want to supply an address

Can only be contacted via a mobile phone

Uses an email address from a supplier such as Hotmail or Gmail

Action to take

Carry out a credit reference

Carry out a Companies House check

Check for a company website

Check Google Street View for a view of the address

Check that addresses and phone numbers tally

See All

See All