The crunchy road to making an Indian brand

It’s hard to believe that at Rs 5,000 crore, the brand value of Haldiram, the makers of the savoury snack called bhujia, is high than McDonald’s and Pizza Hut, especially when it spends very little on promotions. It doesn’t need to, because the brand, started by an impoverished trader from Bikaner, Rajasthan, who tasted the market at the grassroots, it has struck to the first rule of business — know what the customers want and deliver it. In the book, Bhujia Barons: The Untold Story of How Ha

22 Dec 2017 | By Dibyajyoti Sarma

It’s a rags-to-riches story indeed. However, what sets it apart from other such stories is how most of this was serendipitous than actual planning, and how it was guided by survival instinct and how it was a result of a curious, often fraught amalgamation of traditional way of doing business and adopting innovations.

The ubiquitous bhujia, a popular pan-Indian snack, was first introduced in Bikaner in 1885. Those were the thicker version, before Haldiram introduced the thinner version in 1920s, for which he designed a proprietary sieve with smaller holes.

Building a brand

Born in 1908, Ganga Bhishen Agarwal, who would later be known by a nickname his mother gave him, Haldiram, started making bhujia at the age of 12. By then, Bikaner was a thriving trading town, and when Bhikharam Agarwal, Haldiram’s grandfather, needed to find a trade, he decided to fall back on a family recipe, taught by his daughter, which she picked up from her mother-in-law. It was a small shop selling bhujia on day-to-day basis, for it was a perishable item. Family lore says Haldiram, working at his grandfather’s shop, perfected the recipe for which it is still known. A brand was born — Haldiram’s bhujia.

At the age of 35, still making the popular bhujia, he was already the father of three sons and one grandson. Then one day, at the insistence of his wife, he broke away from the family business. Penniless and nearly on the street, Haldiram got Rs 100 from a friend and started a new venture, selling moong dal, made by his wife, on a cart. This venture too worked. But Haldiram’s heart was in making bhujia. So when he found an opportunity to open a shop in the premises of the Chintamani Temple in Bikaner, he took it. The shop was called Haldiram Bhujiawale — the brand came into existence.

For an impoverish family of traders, making bhujia every day and selling it in a reasonable profit would have been a good business proposition, and Haldiram and his family would have been satisfied with it. However, a chance visit to Kolkata to attend a wedding changed everything. Haldiram made his trademark bhujia for the guests in Kolkata and it was an instant hit. So the idea of setting a shop in Kolkata was floated. Though Haldiram was resistant to the idea in the beginning, he finally relented and sent his two youngest sons and his first grandson, Shiv Kishan, who would later play an important role in expanding the Haldiram empire from Nagpur, to Kolkata. The expansion had begun.

Expanding a family business

There was very little capital investment. They started small in Kolkata, as they did in Bikaner, selling the snack on a cart, giving it to customers in newspaper cones, introducing a new taste in the market. As the popularity grew, they gradually scaled up, first a small shop and then a bigger one. Finally, the business was divided into the two brothers, the youngest of whom started an independent venture, Haldiram and Sons. This was the first of many divisions within the family business (some involving bitter legal battles), all capitalising on the legacy of Haldiram, who remained the grand patriarch of the divided family up until his dead in 1980s.

Then in early 1970s, another serendipitous chance took the third generation visionary Shiv Kishan to Nagpur, where he experimented on other items, besides bhujia and increased the scope of the Haldiram brand by established a series of sit-down restaurants. No wonder, today Nagpur is the headquarters of the main Haldiram brand, Haldiram’s.

How packaging changed the business

The foundation of the empire had been laid, but the model was still family owned trading. They had by then three locations, in Bikaner, Kolkata and Nagpur, and several selling points in the latter two cities. However, they were servicing only local customers, from their designated selling points. The packaging was still newspaper wrapping. Even the product had limited shelf-life (the bhujia had to be made every day like any other traditional Indian sweet) and there was no distribution network to sell it in retail stores pan-India as it is now.

One must understand that it was a business run by the workers themselves. Haldiram got his name by making bhujias, not just selling them. Even the next generation did not have much education, and everything they learnt about the business was hands-on and traditional. So there was no marketing, no packaging.

So, what was the secret of Haldiram’s early success? Pavitra Kumar has the answer. She says the reason Haldiram became popular was because he could catch the pulse of people’s taste at the grassroots and gave his customers what they wanted, as savoury which was ‘swad se bharpoor,’ as one of Haldiram’s grandsons explains in the book. It was this customer loyalty that played a major role in the brand’s success. Even after all these years, the family recipe remains the same, so are quality and taste.

The next major change in the Haldiram empire came when they decided to package the bhujia in plastic bags in 1970s. While Prabhu Shankar Agarwal, the current owner of the Kolkata business agrees that packaging was the main reason behind Haldiram’s success, the grand patriarch and his eldest son, Moolchand, was opposed to the idea in the beginning. This was the first clash between tradition and innovation. Haldiram was doing well and he was satisfied with it. He could not think beyond a growth trajectory where one or the other family member was not directly involved in making and selling the bhujia.

With the third generation actively involved, however, it all changed. The first step to packaging was low quality plastic bags where the bhujia was poured and then stapled, with the brand name ‘Haldiram Bhujiawala’ printed in letterpress. But this did not work, as words printed on plastic in letterpress would get smudged during handling. Yet, the company saw a demand for packaged bhujia from other traders. While the elders remained opposed to the idea, Moolchand’s son Mohanlal met with the people from Alphaflex Printing in Delhi who offered flexo printing in multiple colours. It was still a new technology in 1970s and the colour-printing results were stunning. So Mohanlal designed the famous V-shaped logo in red and white. But the cost of 15-16 paisa per packet appeared to be exorbitant. There was more resistance at the fear of losing profit margins. Mohanlal says in the book that he decided to take the risk anyway for some time and see what happened. The trick worked and Haldiram’s bhujia was now available in packages in local retail stores.

The brand name had been established. What was needed was way to reach out to more customers. This was done, and as they say, the rest is history.

The story of Haldiram and his bhujia is far from over. In 1970s and 1980s, Haldiram’s grandsons came to the fore and took more risks (including opening a business in the capital) expanded the business, initiated several new innovations (including the introduction of zip pouches for bigger bhujia packs) while fighting number of stumbling blocks, both outside competition and in-fighting within the family for individual shares. In this fascinating book, Pavitra Kumar describes these milestones of the sprawling family saga with breathtaking details. A worthwhile read.

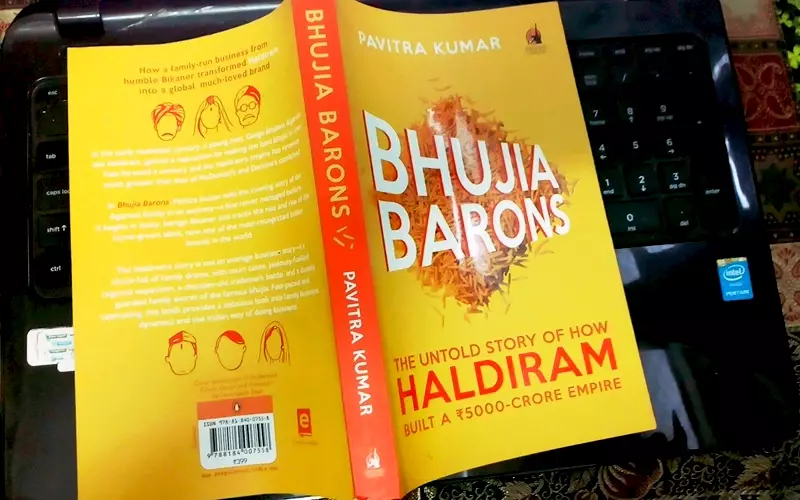

Bhujia Barons: The Untold Story of How Haldiram Built A Rs 5000-Crore Empire

By Pavitra Kumar

Penguin Portfolio

Pages 220

Price 399

See All

See All