A journey through letterpress typefaces

Print expert Arun Bapurao Naik was in the UK recently to talk about the legacy of letterpress printing in India. The following is the highlights of his presentationz

01 Mar 2019 | By PrintWeek India

Print expert Arun Bapurao Naik recently travelled to the UK to speak about the legacy of letterpress printing in India at the Letterpress: Past, Present, and Future conference organised by the University of Leeds and Birmingham City University in the UK. The conference was held on 19 and 20 July 2018 at the Business School, University of Leeds.

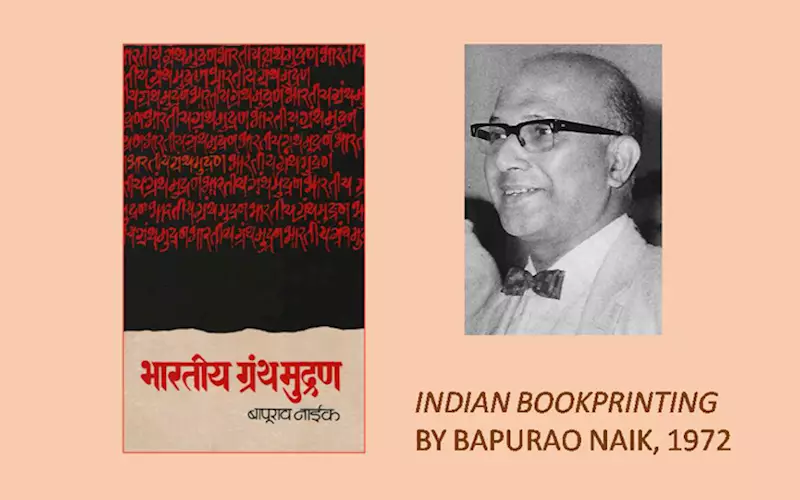

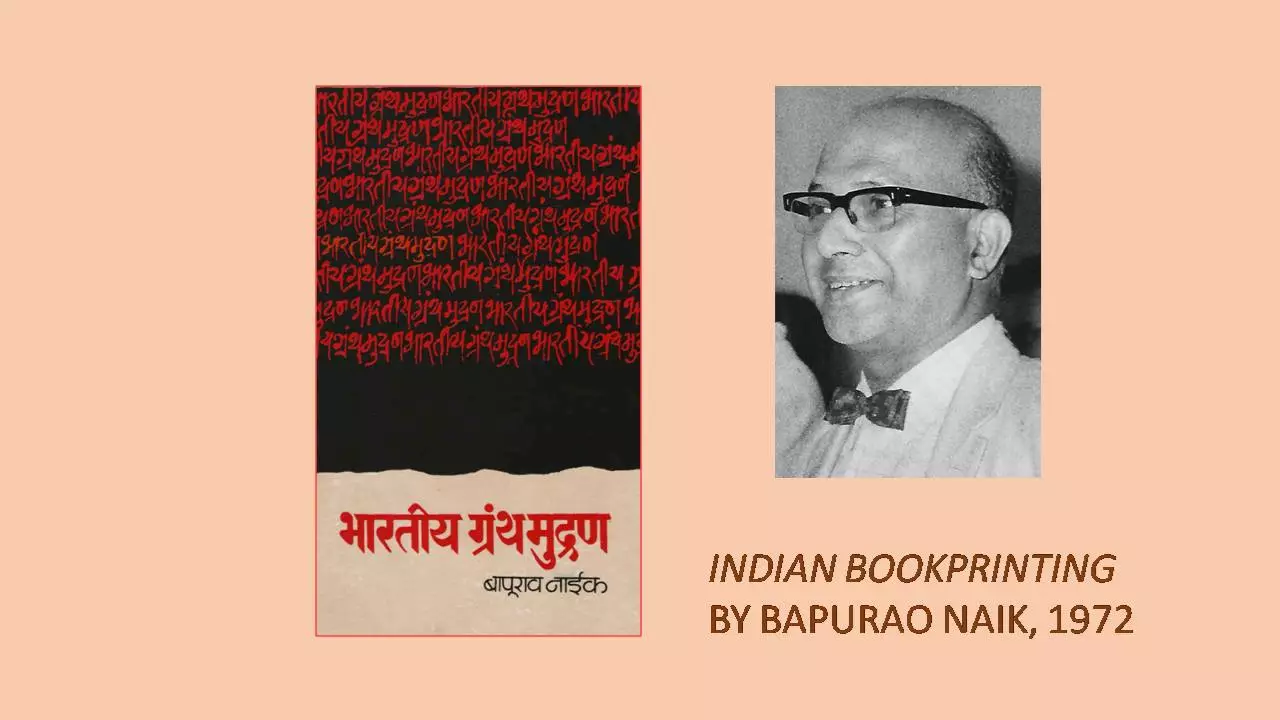

Son of the legendary Bapurao Naik, who wrote the monumental Typography of Devanagari in three volumes, Naik was associated with the print firm Akshar Pratiroop. He was a Graphic Arts Technology Foundation fellow in 1988 and has been a member of the Bombay Master Printers Association and the Maharashtra Textbook Printers Association. He was also the editor of Print Bulletin and MC member of MMS as well as BMPA.

Besides being a print expert, Naik wrote a book on paper for Standard VIII students called Kagad (1994) and also translated Shakespeare’s Hamlet.

The conference focused on the changing trends of printing in the twentieth century when it shifted from a craft-based to a technology-led process. The composing room moved from hand to machine composition, from photosetting to digital; while the press room shifted from letterpress to offset lithography and latter digital methods of production. Technical progress, however, failed to completely usurp traditional printing and today there is a marked increase in those engaged with older methods of production, whether for pleasure, profit, or scholarship.

During his presentation on the ‘Legacy of letterpress printing in India,’ Naik offered an overview of the development of letterpress types in India, as well as in Indian scripts.

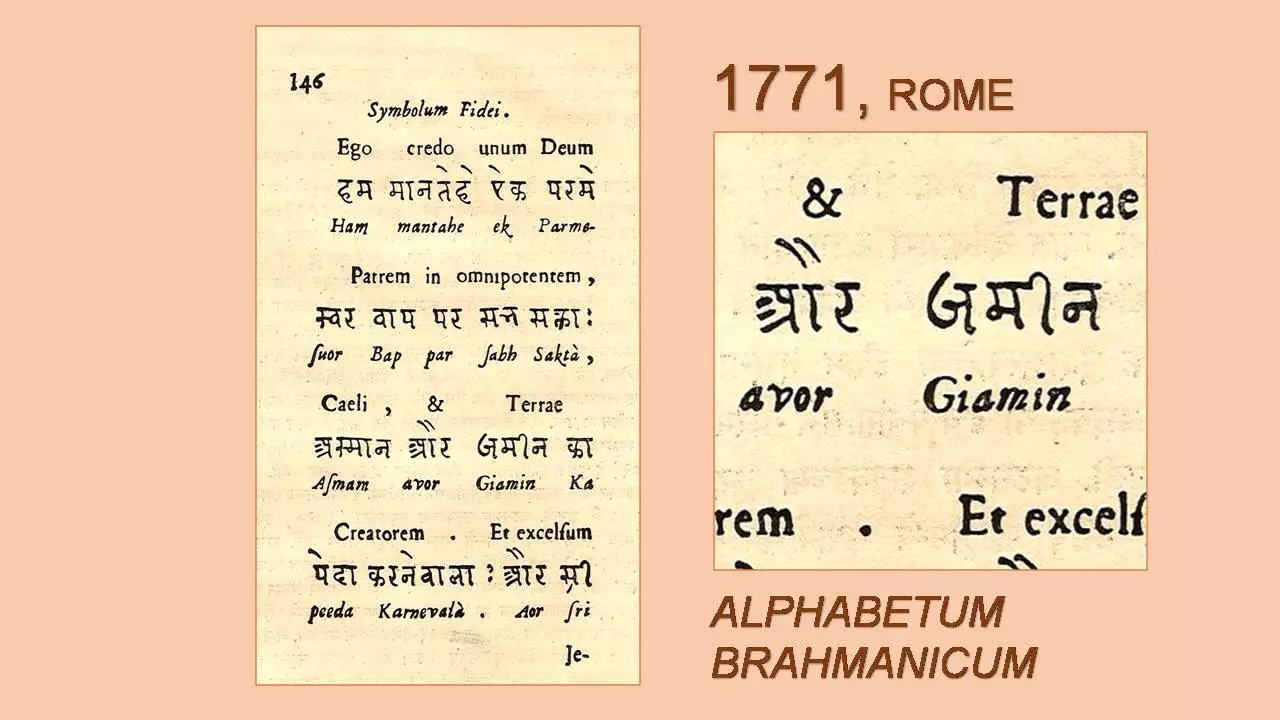

According to Naik, the first local language letterpress typeface, Devanagari, appeared in a book titled Alphabetum Brahmanicum, printed in Rome in 1771. This was the result of an attempt by the Vatican to print The Bible in the local language.

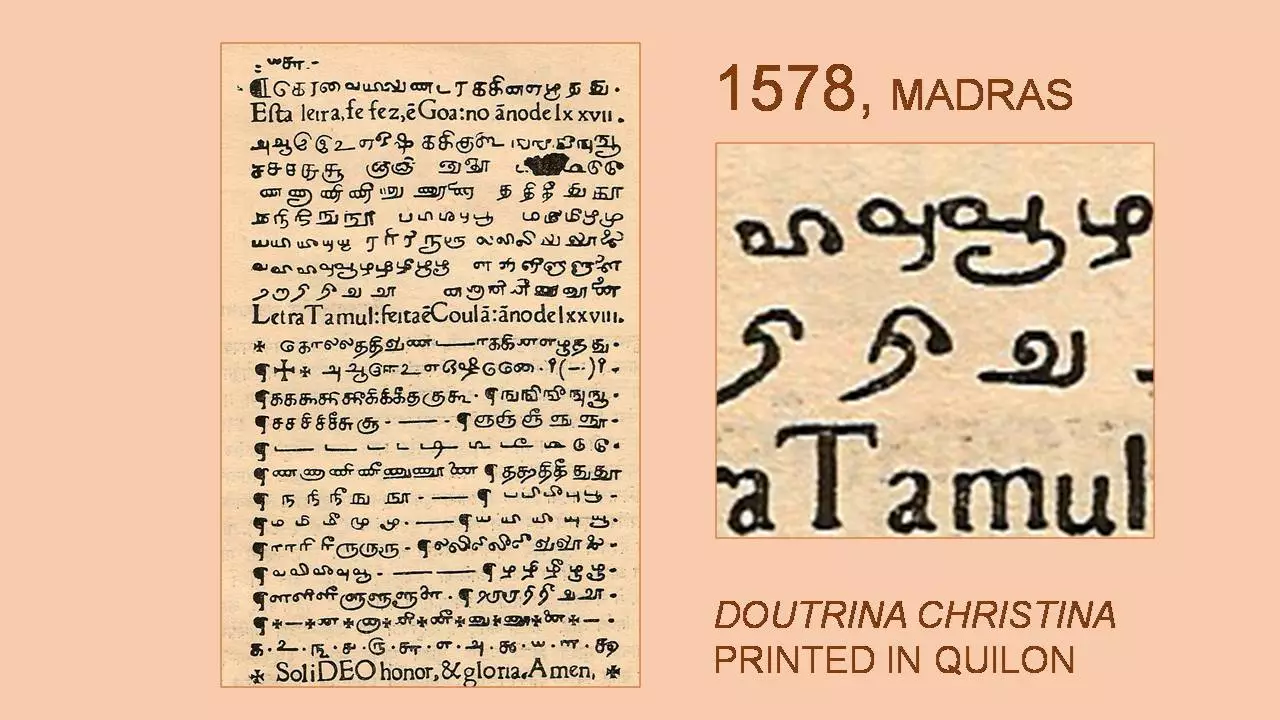

The early appearance of Tamil moveable type is evident in Doutrina Christina, published from Madras, today’s Chennai, in 1578, and printed in Quilon, today’s Kollam, Kerala. It was the Tamil translation of a Portuguese catechism.

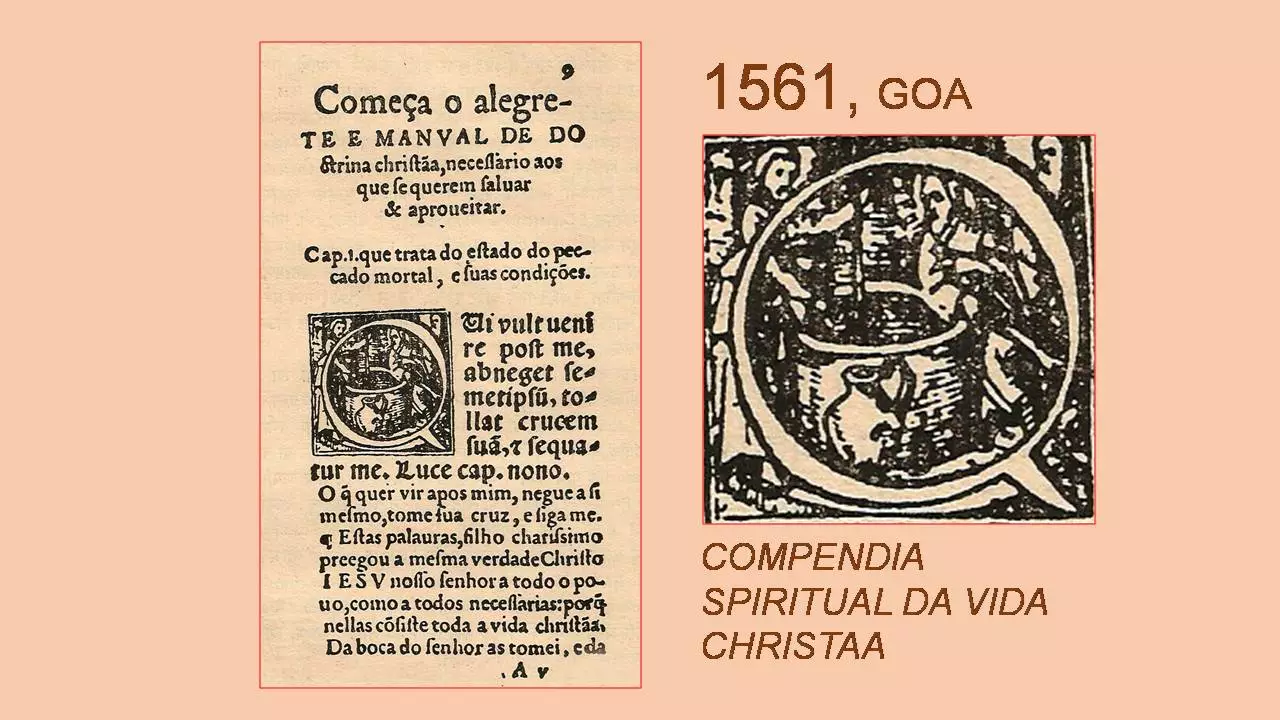

The Latin type appears in Goa in 1561 in the book Compendia Spiritual Da Vida Christaa.

Naik also gives the example of a font type in Banianor Guzerat character, which was invented and cast by Behramjee Jeejeebhoy and Nursunjee Cowasjee. The type was added to the printing stock of the Bombay Courier. On its 12 November 1796 issue, Bombay Courier ran an announcement, reading: “The Public are hereby informed, that business will hereafter be executed in this Type, (with the exception for the present, of Advertisements in the Newspaper) upon the same terms as in the English Character. Bombay Courier Office, 9th Novr, 1796.”

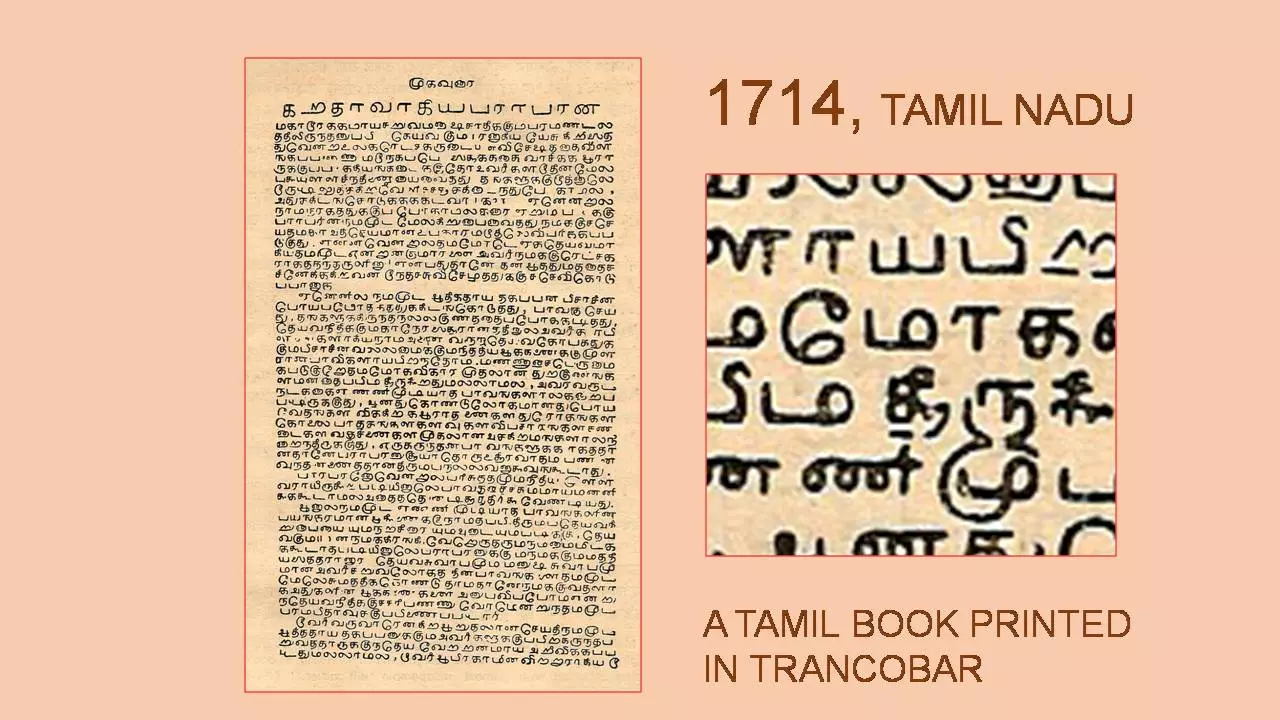

Naik presented another example of Tamil type in a book printed in Trancobar (Tranquebar, today, Tharangambadi) in 1714.

How the Devanagari type developed since 1771 is evident in a page from Nana Phadnis’s Bhagwat Geeta printed in 1805 in Poona.

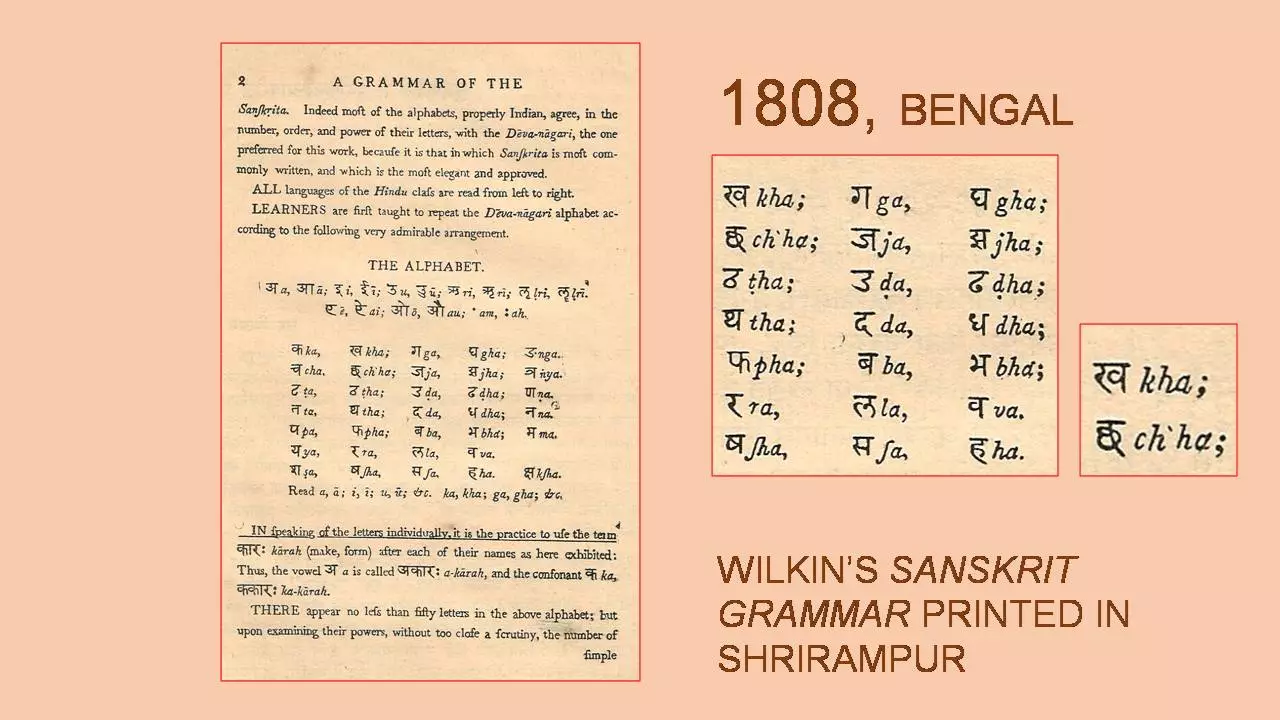

Three years later, in 1808, we notice a combination of Latin and Devanagari types in Charles Wilkin’s A Grammar of the Sanskrit Language. The book was printed in Shrirampur.

While working for the East India Company in Bengal, Charles Wilkins (1749-1836) became one of first Europeans to master the Sanskrit language. He proceeded to set up a printing press in Calcutta to publish works in Sanskrit and other Indian languages. Wilkins also undertook related projects, including A Grammar of the Sanskrit Language in 1808, which was part of his larger scheme to write a dictionary of the language and to translate the Mahabharata. The grammar was the only part of the project that was completed. The grammar attempted a comprehensive explanation of the language, ranging from the Devanagari alphabet to indeclinable words, and it was a vital resource in making Indian languages accessible to an English-speaking public.

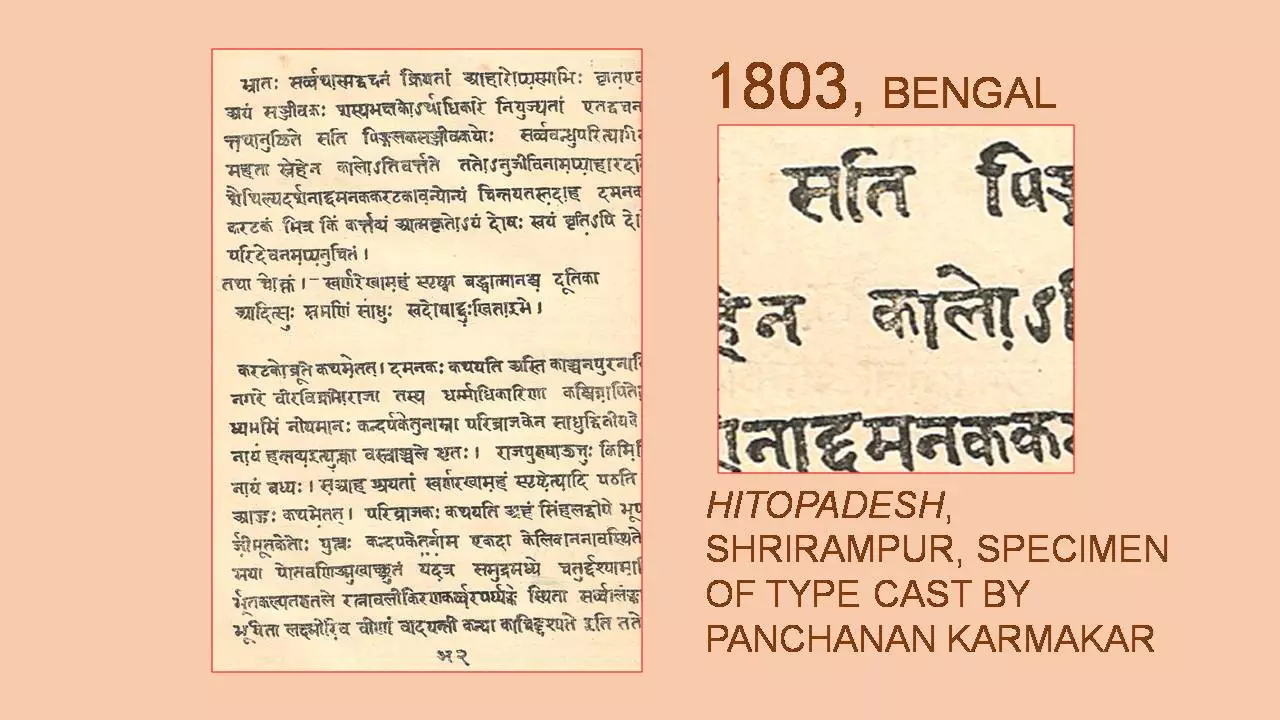

Meanwhile, Panchanan Karmakar, who invented the Bengali font, had already started casting Devanagari types. An example of this can be found in Hitopadesh, printed in Shrirampur in 1803.

Panchanan Karmakar (died c 1804), who created the Bengali typeface under the supervision of English typographer Charles Wilkins, was born in Hooghly district. His ancestors were calligraphers, who inscribed names and decorations on copper plates, weapons, metal pots, etc.

In 1779, Karmakar moved to Kolkata to work for Wilkins' new printing press. In 1801, he developed a typeface for British missionary William Carey's Bangla translation of the New Testament. In 1803, Karmakar developed a set of Devanagari script, the first Nagari type to be developed in India.

He developed the Bengali type to print Nathaniel Brassey Halhed's A Grammar of the Bengal Language. The book was printed at the printed press owned by Andrews, a Christian missionary.

William Carey was another important name during the early development of local language typefaces, as he was instrumental in translating The Bible into Bengali, Oriya, Assamese, Marathi, Hindi and Sanskrit. It was the first printed text in many of these languages. Since there was no type available, William Ward had to create punches for the type by hand.

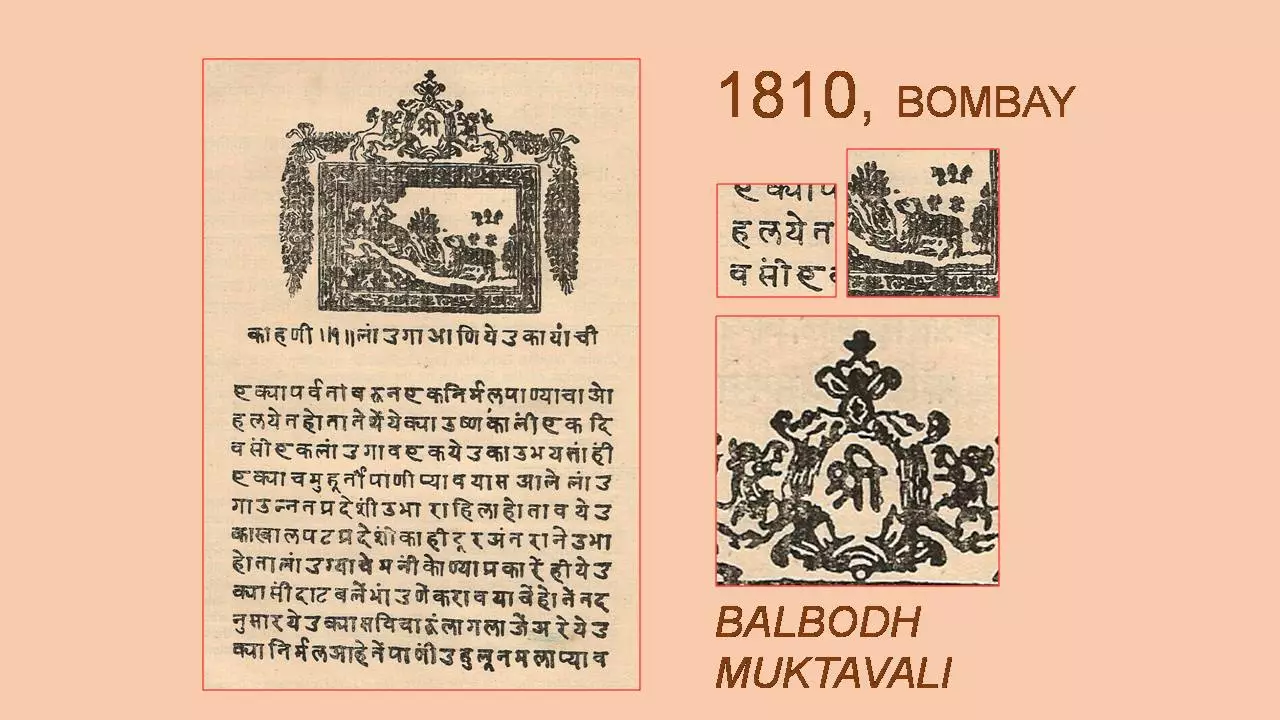

In 1810, we see an early example of Marathi type in Balbodh Muktavali printed in Bombay. In an attempt to print books in ‘the language and alphabet of the land’, the book was printed with the help of the Danish missionaries at the initiative of the Maratha King Sarfoji in Tanjore.

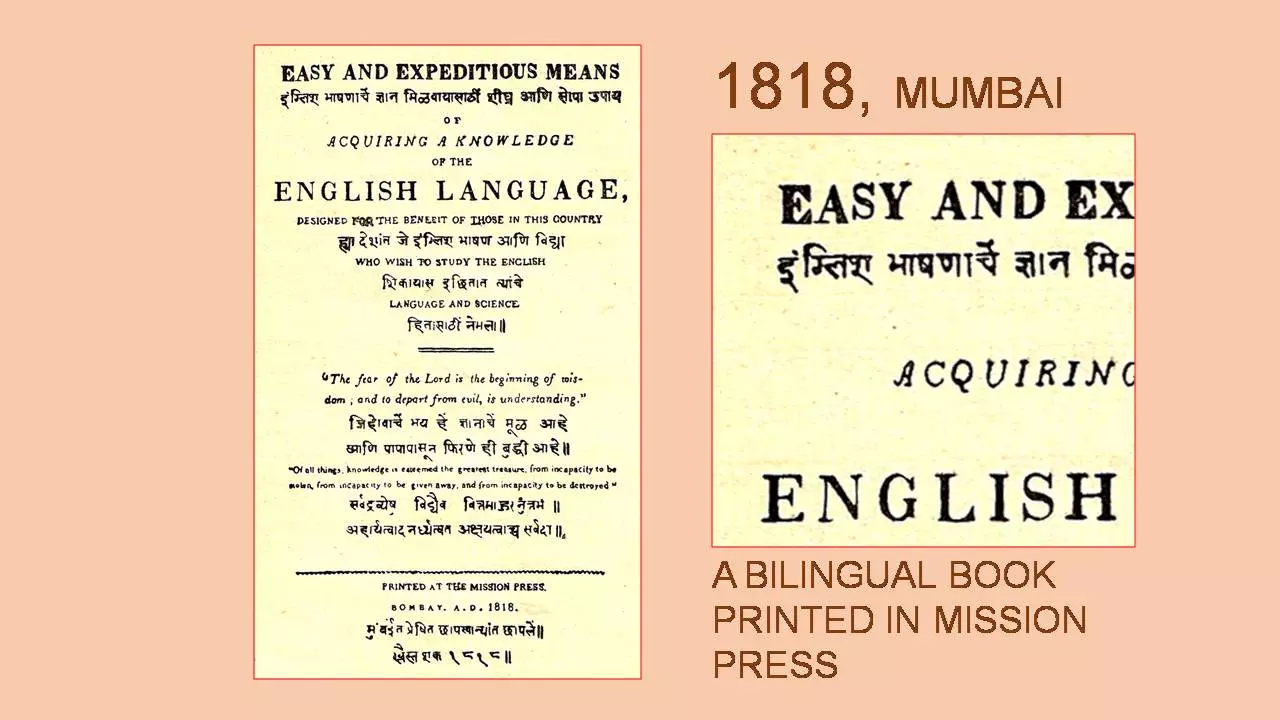

Besides spreading Christianity, another major use of letterpress during the early years of the nineteenth century was to create education material for the common public. While the East India company employees and the Christian missionaries sought to learn Sanskrit and other local languages, they also attempted to teach the local population the English language. One of the comprehensive ways of doing this was to print bilingual texts.

We notice one such example in the Marathi and English, Easy and Expeditious Means of Acquiring Knowledge of the English Language, which was printed at the Mission Press in Bombay in 1818.

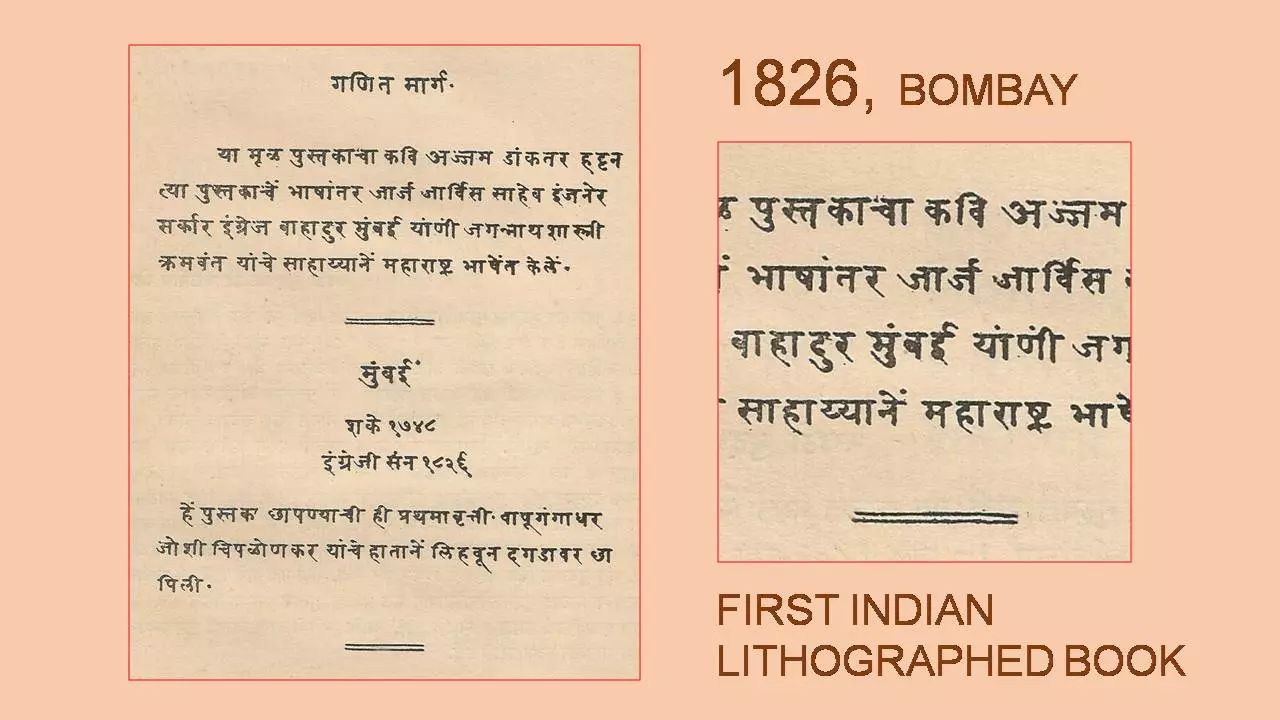

The first Indian lithographed book was printed in Bombay in 1826.

Around the same time, lithographed books started to appear in Benares, Agra and Calcutta. Then, in 1858, the Nawal Kishore Press came into being in Lucknow.

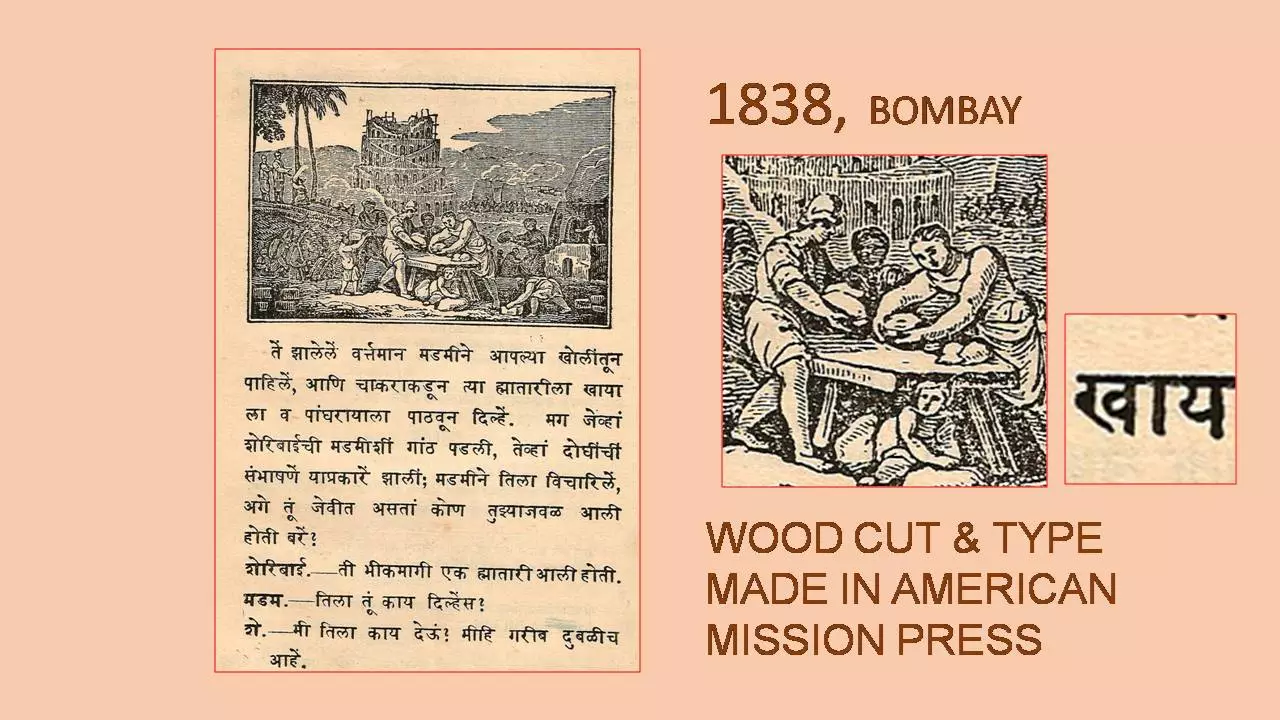

During his presentation, Naik also showcased an example of wood cut and type made in American Mission Press in Bombay in 1938, used in a Marathi book.

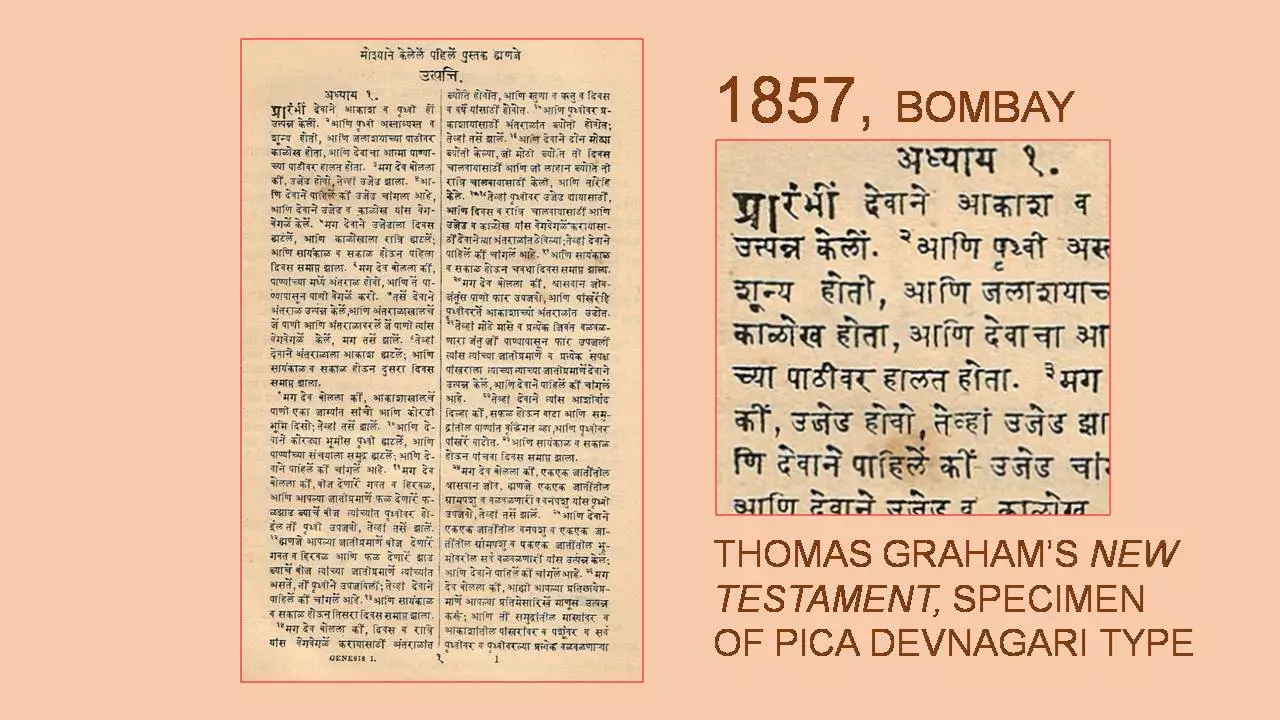

We notice the evidence of using Pica Devanagari type Thomas Graham’s translation of The New Testament printed in Mumbai in 1857.

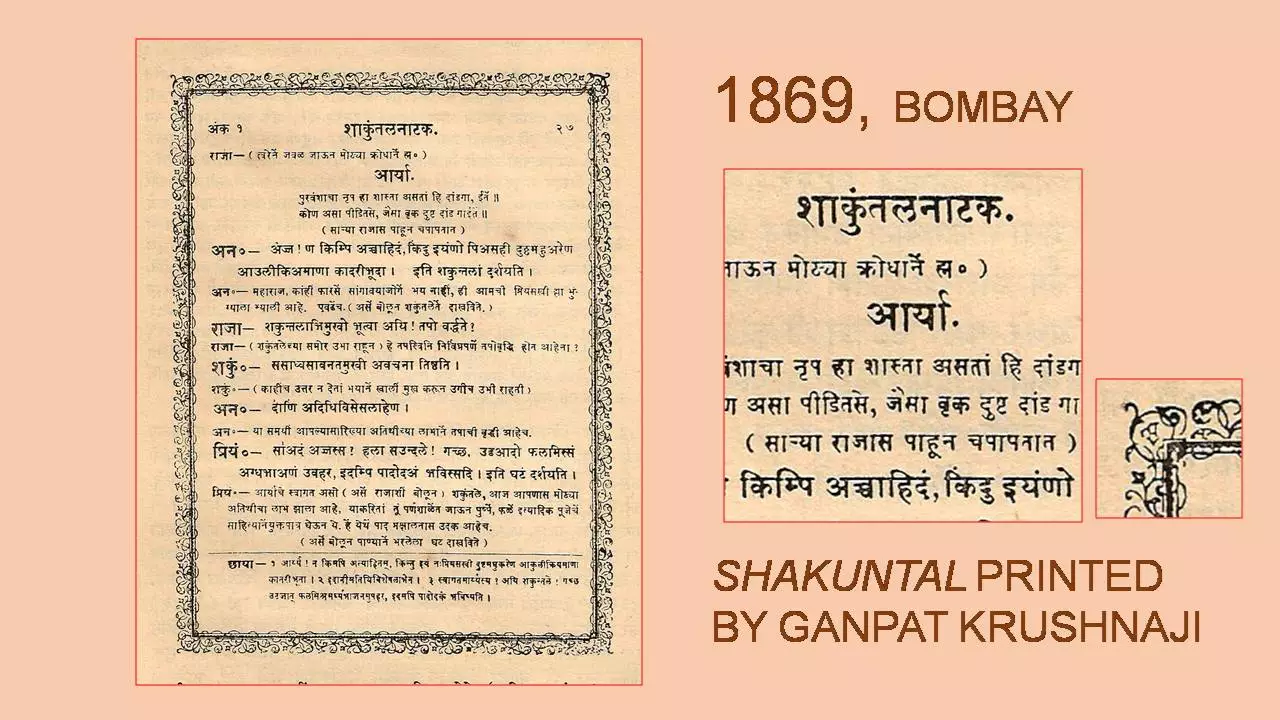

Up next, Naik presented a page from Shakuntal Natak in Devanagari, printed by Ganpat Krushnaji in Bombay in 1869, and then a Marathi textbook printed by Jawji Dadaji in Bombay in 1910.

Before that, eight-point Marathi type designed by AARU makes an appearance in Bombay in 1892.

Naik concluded his presentation with reference to the classic Indian Bookprinting by Bapurao Naik, published in 1972.

See All

See All